Industry in the Vale of Leven - Page 3

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 4 | Page 5

In 1790, William Stirling & Sons of Cordale and Dalquhurn came further up the River to open Croftingea Works as a bleaching field. Croftingea was contracted by Vale folk to “the Craft” or even sometimes “the Croft”, and even after the Alexandria Works were formed in 1860, that name, still in use, was transferred to it. In 1790 when it opened, Croftingea was close to, but by no means adjacent to, Levenfield Works being about 500 yards south of it on the west bank of the Leven. Eventually, Croftingea and Levenfield were amalgamated in 1860 to form Alexandria Works.

The "Craft" or Croftengea works today. Above

the blue car you can just see India Street

where the factory gate was

situated. (Click to Enlarge)

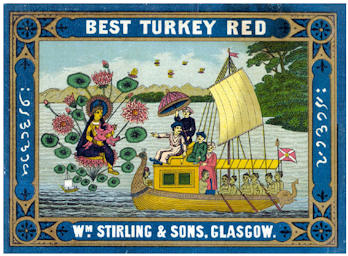

It was at Croftingea in 1827 that the first commercially successful Turkey red dye was made and used. This dye laid the foundation for the success of the Vale for the rest of the 19th Century as the centre for the bleaching, dyeing and printing industry in Scotland, with markets from India to Africa, as well as Europe.

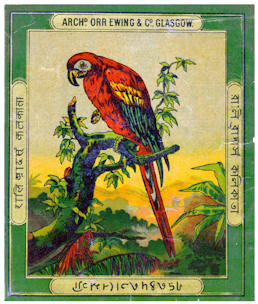

The people who most successfully exploited this success were the Orr Ewing brothers. It turned out that John Orr Ewing owned factories on the west bank of the Leven, while his brother and competitor, Archibald, owned factories on the east bank. John Orr Ewing built a major factory and multi-process textile operation around the old Croftingea works, including the 300 feet high Craft Stock, during his first period of ownership between 1845 and 1860. He sold it and when he returned 15 years later, it was mainly because the business had declined under the management of the person he had sold it to.

On John Orr Ewing's return in 1860 he set about restoring the works fortunes. He bought Levenfield and was contiguous with Croftingea and renamed them the Alexandria Works. By then about 1,000 people were employed in Alexandria Works. Apart from some alterations in the period 1880 - 1900, and the inclusion of the Charleston Engraving Works when the UTR formed in 1897, Alexandria Works retained the same layout until their closure in 1960.

After the formation of the United Turkey Red Ltd company (the UTR) in 1897 (of which more below), the Alexandria Works became the de facto main works for the UTR. This was not just because most of the top management of the UTR had previously managed Alexandria Works, it was also because it was better equipped across a wider range of functions than any of the other factories. It had a large range of printing machines and a large number of them. It had a bleaching and finishing plant, a colour shop and an engraving shop. It could dye in a variety of ways. It could do just about anything that any of the other plants could, while each of them could only do 1 or 2 of the things it could do.

Textile Trade Tickets: The colourful images on this pages are of pictorial “tickets”, which were added to each length of cloth produced by the Turkey Red industry in Alexandria in the late nineteenth century. The link above is a downloadable PDF about these. (Note that this file is about 17Mb so it may take a few seconds to download.)

WW1 had barely any impression on it, it operated throughout the Depression

at reduced output levels and with industrial relations problems, but it survived

the Depression. The management of the UTR emerged  from WW2 knowing that their

markets had dramatically changed and they would have to change too to have

any chance of surviving. By the 1950's

the Craft was basically a multi-purpose textile processing plant, capable of

doing a range of things unheard of before. This included knitting machinery

for nylon knitwear and screen-printing.

from WW2 knowing that their

markets had dramatically changed and they would have to change too to have

any chance of surviving. By the 1950's

the Craft was basically a multi-purpose textile processing plant, capable of

doing a range of things unheard of before. This included knitting machinery

for nylon knitwear and screen-printing.

The management was obviously trying to cover as many bases as possible, in the hope that one or two would turn out sufficiently successfully for a sustainable business to be fashioned around them at the Craft. It was not to be, and in 1960 the perhaps inevitable happened when the UTR Board sold out to the only buyer in town, the old villain of Ferryfield and Dalmonach, the CPA. With indecent haste the CPA closed Alexandria Works in 1960.

Note: In 2011 The National Museums of Scotland took on a project called "Colouring the Nation". Their task was to photograph pattern books produced in the 19th Century by Scotland's textile printing and dyeing companies. Naturally the Vale companies featured high on their priorities. Some 500 high res images are now available to view on a website specifically created for this project.

These images are a potent reminder of just how good the Vale companies were not just at printing and dyeing but also at creating outstanding visual art. They provide ample proof of the claim that the William Stirlings and the Orr Ewings were indeed world leaders in Turkey Red dyeing. Well worth a look.

http://www.nms.ac.uk/turkey_red/colouring_the_nation.aspx

So that was more or less the end of the UTR, but it was not the end of Alexandria works by any means. Some parts of it were demolished - including, in 1964, the 300 foot high Craft Stock. Although held in great affection by the people of the Vale, it would have had to be demolished sooner or later anyway. The fact that it came down to make way for a whisky distillery softened the blow. The whisky distillery - Loch Lomond Distillery, distillers of the excellent Inchmurrin whisky amongst other brands - and its associated company Loch Lomond Bond, were but two of the companies which set up in the now empty buildings. The works were renamed the Lomond Industrial Estate, and have housed many companies over the years.

These include:

- Antartex who moved their sheepskin clothes business from Dalquhurn to the Croft in the late 1960's. They did reasonably well for a number of years, but were in a continuous dispute with the local authorities about being allowed to put up direction signs from the A82. This was totally refused to them on the basis of road safety, so it seems, at best, ironic that newer developments have been allowed to be put direction signs up, with no more mention of road safety hazards. No doubt there is an excellent reason for the change of policy. Eventually, the owners closed their manufacturing operations and went into retail on the same premises. A substantial and successful retail operation is still on the site, under new ownership.

- Scottish Colorfoto carried on a successful photo print business on Lomond Industrial estate for many years.

- When they closed down, Roberts Engineering transferred their light engineering works from Dillichip to the ex-Scottish Colourfoto building.

- Royal Mail took over the building when Roberts Engineering was bought out by Motherwell Bridge and the operation transferred to Cumbernauld. Royal Mail use it as the area's sorting office

- Lomondprint have a successful printing business on the Estate

The first appearance of a local supplier company to the textile factories is in the 1790's. Millburn Pyroligneous and Liquour Works were opened to produce dyeing liquour from wood. It was owned by the Turnbull family, and was close to Place of Bonhill House, which they occupied and renovated from 1806 onwards. It was located partly in Millburn Quarry, and replaced an old water mill, which stood there (hence “Mill Burn”), and partly on the land which is now Argyll & Bute's Millburn Roads Depot. Part of it was, therefore, more or less on the site of the rail tracks of the Bowling - Balloch line, and that part was closed and demolished when the railway was being built in the early 1850's.

It was not the only works in the area which made dyeing liquour for the dye works. At Jamestown Arthurston Mill, the “Chip Mill”, soldiered on until 1910, while at Balmaha, there was a similar liquour works in the middle of the village, which operated until 1920. It delivered the liquour in barrels to the works on the banks of the Leven by steam lighter, which even in the 20th century was easily the most efficient mode of transport.

The next factory to be built was Bonhill Printworks or “Langs Wee Field”, or just “the Wee Field”. It was opened in 1793 by Gilbert Lang & Co between the Bonhill Parish Church of the day and Bonhill Ferry. In spite of it size it seems to have been quite aggressively successful in its time. Its profits maybe are not so surprising when you consider that it had easily the highest proportion of child labour that we know about, of the factories in the Vale - about 100 out of a work force of about 400. For some reason, there are a number of illustrations of the Wee Field, which is just as well, because it was closed and demolished in 1840, just before photography was becoming widely applied, at least in the Vale

By 1800 there were in the Vale, therefore, four bleachfieds and three print fields working on cotton. The numbers employed varied a bit between summer and the rest of the year, because bleaching itself was carried out only in the summer until 1841, when an indoor bleaching process was introduced in the Vale. Highlanders came down to work in the bleach fields in the summer and returned home in the autumn. Even factoring in this seasonality, there were about 1,000 full time equivalent jobs in the bleaching and printing works in 1800.

Also by 1800, there was a foundry in the middle of Alexandria, in what was Smiddy Street, now Susannah Street. This was owned by a Mr Gardner and was well placed to supply Ferryfield, Levenfield and Croftingea works. The foundry changed hands about 1870 and moved to its present site at the foot of Wilson Street in 1884. Sharp & Co owned it in the early 1900's. It survived the Depression becoming part of Dryburgh's of Yoker (who themselves became part of Weir Pumps) sometime after WW2, by which time it had already been named Lennox Foundry. That name can still be seen on the building, although it has long since been used for other light engineering purposes by a number of other firms.

Dillichip Bridge

Dillichip Works was founded by Turnbull & Arthur in the1820's as a Bleachfield, but became a Printworks in 1848. It had an uneven history, but in the late 1830's it was employing 565 people, including 63 children. In 1866 it was taken over by Archibald Orr Ewing and its fortunes improved. In 1875 it had its own branch line built into the centre of the works, from the main line, just south of Alexandria station, across the Leven on its own bridge, the Dillichip Bridge. It became part of the UTR when that was set up in 1897. It closed in 1936, but the buildings survived. During the war it was taken over by the REME. From 1947 - 1956 it was used by the Paisley based textile company of JP Coats. Since shortly after then it has been in use as a whisky bond.

In 1827, the fortunes of the Vale, which were in pretty good shape anyway, took a turn for the better. In fact, for a small group of owners, chemists and managers, they took a spectacular turn for the better. They became rich, some of them very rich indeed. This was caused by the successful creation of the process to make a Turkey red dye at Croftingea works. It is impossible now to fully grasp the importance of this discovery for the factories of the Vale. While Turkey red had been around for a very long time in Persia and Greece, no one in the UK knew how to make the very bright red, very fast dye. Since the UK, as the colonial ruler, controlled access to the two biggest markets for the dye - India and West Africa - a fortune awaited its innovator.

It gave the Vale works a leadership position in dyeing over all their competitors in the UK, from 1827 until the introduction of a Napthol based dye in 1914. Then the advantage was lost, but that was only one of a number of problems facing the works by then.

The Charleston Engraving Works was founded in 1830 to make copper engraving plates for the printworks. It was located beside the Croftingea works in an area then called Charleston. Charleston Row called “Red Row” was the main access road to Croft works and the Leven in 1830. It remained independent until 1897, when with the formation of the UTR it was taken over by the UTR and incorporated in Alexandria Works.

Like the Wee Field, there is now no trace left of the last of the Vale textile factories to be built in the 19th Century. This was Kirkland Printworks, Bonhill, which was opened in 1836 on the east bank of the Leven a couple of hundred yards from Dillichip. In 1841 it employed 224 people of which 83 were children. It was bought by Alexander Orr Ewing in 1860. Since he already owned, and was expanding Dillichip, he had no need for Kirkland so he had it demolished in 1860.

In 1897 the clearest possible indication of the increasing competition and financial pressures being felt by the Vale textile companies was evidenced by the decision of three of them to amalgamate. William Stirling & Sons, John Orr Ewing and Co and Archibald Orr Ewing and Co amalgamated to form the United Turkey Red Company Ltd (UTR). At the same time the UTR bought the Charleston Engraving Company.

In 1897 the clearest possible indication of the increasing competition and financial pressures being felt by the Vale textile companies was evidenced by the decision of three of them to amalgamate. William Stirling & Sons, John Orr Ewing and Co and Archibald Orr Ewing and Co amalgamated to form the United Turkey Red Company Ltd (UTR). At the same time the UTR bought the Charleston Engraving Company.

The six factories, which were included in the UTR, were:

- From William Stirling & Sons Company, Dalquhurn and Cordale

- From the Archibald Orr Ewing & Co, Dillichip, Milton, Levenbank

- From John Orr Ewing, Alexandria Works (the Craft)

The UTR had now between 5,000 and 6,000 employees and it was by far the largest firm in the bleaching, finishing, dyeing and printing industry in Scotland. It became a recognised name on a worldwide basis. It was an amalgamation born of necessity, and it prompted 46 of their British counterparts to take similar steps two years later with the formation of the rival CPA in Manchester in 1899.

The major problems facing them were in their markets, where not only were they facing cheap imports from Japan, but also there were accusations that India was placing import duty barriers on British textile imports so as to cultivate a home-based industry. In any event, Indians themselves, including Gandhi at a slightly later stage, were beginning to start up their own cottage-based industry, with or without a tariff. The idea of the merger was good business sense at the time. The only public opposition came from the workers, many of whom feared the creation of a monopoly in the employment market in the area.

Their fear was that up until 1897, if you fell out with one employer, you could, and usually did, easily move to another. This was not entirely a worry about nothing, because one of the defining characteristics of the merger was that labour relations seemed to get worse after it. However, immediate success or failure was going to be measured in financial performance, and that depended on how the merger was implemented.

To begin with the commercial authority of each company was preserved. That was probably a bedding-down gesture, because it stopped the UTR from making any financial savings from rationalising duplicated operations. The company was eventually re-organised on a departmental basis, but at that stage comments about remote management had already begun to appear. The Registered Office of the Company became 46 West George Street, Glasgow. That was where the boardroom was, where the directorate came to be based, from where centralised administration and sales operated.

When John Christie, of Christie Park fame, retired from being chairman of the UTR, a management style based on presence and involvement disappeared. For the first time, the top management echelon of the company was no longer based at the Works, nor lived locally. The decline in performance was inexorable, and given the way the markets were going, perhaps partly inevitable. But up until the merger each of the separate companies had seemed to be very competently run, sure-footed, industry leading.

Of course, time and business conditions change and the UTR was not alone in not looking such a well-run company. There was a major strike in 1911, the first in 50 years, which seems with the benefit of hindsight, not only to have been avoidable, but also dragged on longer than it needed to. By this time, most of the workers had joined a union, which the UTR refused to recognise. The union submitted a claim for 10/- a week rise, a 55-hour working week, and extra payment for overtime. The UTR did not deign to reply to the claim.

The union balloted its members, and received a 90% vote in favour of a strike. The strike took place against a background of picketing, throwing blacklegs in the Leven, clashes with police etc. The UTR had to shut down its works, and 10 days after that was persuaded by the Board of Trade to recognise the unions and to negotiate their claims.

From the UTR management's point of view, this was a pretty dismal performance. The management had difficult business conditions to deal with. There was surplus capacity in the UTR even before WW1, and immediately after WW1 this was addressed by closing Milton Works. However, the UTR had major problems from then on. In November 1922, John Christie, in practically his last message to employees, wrote in the UTR Magazine:

“The last eight years have been unprecedented in my lifetime. Following the horrors and wreckage of the War, want of business and unemployment has laid a heavy hand on all of us”.

It is the perfect summation from the person best placed to comment, of the business conditions in the Vale. Throughout the 1920's, even before the Depression set in in earnest in 1929, cutbacks and lay-offs were common. After 1929, they were the norm. Dillichip was run down and then finally closed in 1936. The UTR didn't pay a dividend to its shareholders in 1921 and 1922, but it performed better financially than most of its competitors throughout the 1920's, and made modest profits.

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 4 | Page 5