Balloch Page 1

Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5

Introduction to Balloch and the Earls of Lennox

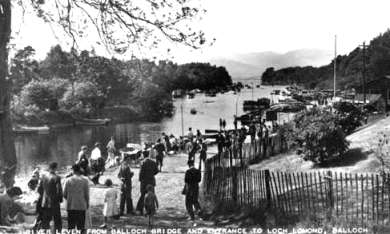

Balloch - Click Image to Enlarge

The name Balloch comes from the Gaelic “bealach” meaning a pass, which is what the land around the southern end of Loch Lomond where the Loch's only outlet, the River Leven, leaves the Loch on its short but fast journey to the River Clyde at Dumbarton, must have seemed like to its early inhabitants and visitors.

It is just south of the Highland Fault Line, where the Highland mountains and hills give way to more fertile land and is the first point at which a relatively easy and safe west-east crossing could be made at the southern end of the Loch. For centuries Balloch lay on a busy water- based line of communication between the Highlands and central Scotland. Although this did not give rise to a very large population centre, it did give Balloch a certain profile from the early middle ages onwards, with the Earls of Lennox having their base at Balloch Castle for some years, and Balloch Horse Fair being one of the most important in Scotland from the later Middle Ages to the beginning of the 20th century.

For centuries, Balloch consisted of the ferry crossing of the Leven, and close by the ferryman's farmhouse that doubled as an  Inn. There were a few houses dotted about, but that was it. It was the growth in celebrity tourism, the arrivals of the Loch steamers and then the railways which kick started Balloch's growth, although cattle droving after the transfer of Scotland's main cattle market to Falkirk Tryst in the 1770's also made a seasonal contribution.

Inn. There were a few houses dotted about, but that was it. It was the growth in celebrity tourism, the arrivals of the Loch steamers and then the railways which kick started Balloch's growth, although cattle droving after the transfer of Scotland's main cattle market to Falkirk Tryst in the 1770's also made a seasonal contribution.

The shape of Balloch as we know it is very much a 20th century creation. Balloch's northwestern boundary now lies about Duck Bay, while Boturich is the north eastern one. The ridge at the top of Stoneymollan is its western boundary and the old Stirling - Balloch railway line is the eastern one. The southern boundary is the Carrochan Burn on the east bank of the Leven, while on the west bank it is northern side of Lomond Road, up to the Stoneymollan roundabout and along the A82 to Duck Bay.

Balloch is unique amongst the Vale towns and villages in that it straddles the River Leven - all the others are on one side or the other. It is further unique in that it is the only town or village that has gone nearly 200 years without a school. In fact there have been two: firstly. firstly, from 1772 until 1816 a Bonhill Parish school was located more or less where the cottage is on the old Cameron Brae, and secondly, there was a small private school from about 1770 - 1800 close to where Castle Avenue now joins Drymen Road.

Balloch also soldiered on until the latter half of the 20th century without a church, and then in short order, and in an even-handed manner, it got two, when the Saints did indeed come marching in. Firstly, in the 1950's, St Kessog's and then, after a name change, St Andrews, which is a combination of three former Alexandria Churches.

These missing centres of typical village life serve to confirm that Balloch was until the 1950's, the smallest of the Vale villages. This belied it longevity and its profile, because along with Bonhill it can trace its recorded history back to the early middle ages, and its position at the south end of the Loch saw it bear witness to many of the most interesting events and developments in the history of the area.

The factories of the Industrial Revolution passed Balloch by, and if the Vale is the end of the industrial central belt, then Balloch is the end of the Vale. It has often seemed over the years that it is where the Vale, and many others, goes to play both on land and water. Increasingly, it has also become where people come to live. Not a bad decision on either count, as Balloch's past shows

The Earls of Lennox

Some reliable impression of what Balloch was like begins to emerge in the 13th century. The Earldom of Lennox had been established some time in the 11th century and the Earls had acquired land, which stretched in a band right across central Scotland from Long Longside to the Firth of Forth around Stirling. Although their first known headquarter was in a wooden castle at Faslane, at various times they had up to 20 castles, keeps or houses within the Lennox lands, stretching from Callender House at Falkirk (close to where the new Falkirk FC stadium is) to Faslane.

Sometime in the early 1200's they decided that Faslane was no longer suitable as their seat - possibly because it was wooden and therefore prone to being set alight by their enemies, possibly they wanted something more central or strategic. They chose a site on the east bank of the Leven just where the river leaves Loch Lomond, and there they erected the first Balloch Castle. It was a stone castle, with a fosse or ditch, which could be flooded. It occupied a commanding position against attack with an uninterrupted view northwards up Loch Lomond, and control of access to and from the River Leven, which was one of the major lines of communications from the western Highlands to the central lowlands, at least until the building of the military roads in the 1740's onwards.

Immediately prior to moving into Balloch Castle as their chief residence, the Earls of Lennox had more or less squatted in Dumbarton Castle. King Alexander II evicted them in 1238 and they then moved into Balloch from Dumbarton - as any sensible person would. The date for the building of Balloch Castle is therefore often given as 1238, but it seems obvious that it must have been built a short time before this. In any event Balloch Castle is given as the location at which the Earls signed charters and documents from the middle of the 13th century onwards.

However, when the Vikings invaded Loch Lomondside in 1263, in the days immediately prior to the defeat at Largs of the Viking army and navy under King Haakon, there is no mention of Balloch Castle playing any part in the mayhem, which ensued. The Vikings had sailed up Loch Long in search of supplies and plunder, pulled their boats across from Arrochar to Tarbet and set off down the Loch. It was well enough known that the Vikings were in the area, but the people of the Lochside felt secure, believing that they were safely inland from the raiders. Some even more prudent souls had taken refuge on the islands. In fact, it didn't matter where you were, the Vikings sought you out. The killing was indiscriminate and widespread, and the pillaging was on the typical Viking scale. In about 3 days what had been a relatively prosperous landscape had been reduced to ruin with bodies strewn all over the place. It is known that some of the Vikings then sailed south down the Leven to the Clyde at Dumbarton and from there rejoined the Viking fleet in Rothesay Bay.

They, therefore, must have sailed right past Balloch Castle. Also, its occupants - if there still were any - must have known the Vikings were on the Loch. Apart from anything else, they must have seen the cottages burning up and down the Lochside. But there is no record of any assistance being provided to the Lochsiders by the Castle, or of any resistance having been offered to the Vikings from the Castle as they sailed past. Why? We don't know, but two possibilities come to mind. The first is that the Lennox forces were already in the field at Largs with Alexander III, and wreaked vengeance on the Vikings a few days later. That's the possibility we'd all settle for. The second is that they all ran away as soon as they knew the Vikings were around. Either way, on the first occasion on which its usefulness could be tested, Balloch Castle has left nothing to history but silence.

By the time of Wallace and Bruce, 30 or so years later, the people of the Lennox were to play a more prominent, worthy role, of which there is plenty of evidence. The lands of the Lennox, particularly Loch Lomondside, were initially a bolthole and hiding place for both men, and if the places named after them - e.g. Wallace's Island and cave - have at best fanciful connections with either, their presence in the area was real enough. Bruce was indebted to Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, who had also been a friend of Wallace, for helping him to hide on Loch Lomondside while he was still fighting to establish himself on the Scottish throne. In later years Bruce commended the men of Lennox for the bravery they had shown at Bannockburn, and he was a firm friend of Earl Malcolm, visiting him at Balloch Castle from his nearby home at Cardross and his hunting lodge between Dalmoak and Dumbarton. He also hunted around what is now Auchendennan.

There's not much left of the old Balloch Castle now - the water-filled ditch is about all. However, James Barr, writing in 1892 / 3 could remember the ruined walls of the Castle of his childhood of the 1820's. Also, Sir Walter Scott, who knew the Leven and Loch well at first hand, having been a frequent visitor to Ross Priory, refers in his novel Rob Roy written in 1817 to “the ruins of an ancient castle, just where the lake discharges its superfluous waters into the Leven”.

It's a fair assumption that visible evidence of the walls survived at least until the 1820's. However it is the road which runs through the park and beside which the ditch lies, which is one of the few remaining relics of medieval life in the Vale and surrounding area, perhaps the only one actually in daily use. It is of at least medieval origin, probably developed or at least strengthened by the Lennoxes. Traces of it remain quite distinct, and we have a good idea of the line it took from Dumbarton Castle through the Vale and along the Lochside to the Pass of Balmaha. It ran alongside the Leven from what is now Balloch Hotel right through what is now Balloch Park and along the side of the Loch to Aber village, which was on the southern bank of the Endrick, close to where it joined the Loch.

Most of the riverside and Lochside road in Balloch Park, right to its boundary with Boturich, is on the line of the original medieval track, and has been built on top of it. While the parkland would have, of course, been unfamiliar to the medieval Lennox folk (the whole area was probably heavily wooded and covered by native trees such as oak), they would have felt quite at home on to-day's Park road.

The Middle Ages were an extremely turbulent time in Scotland. We were either under attack from the English or the leading Scottish families were in a constant struggle for control of the country during regencies often brought on by kings being too young to rule, or imprisoned in England. These two circumstances were all too frequently related, and were to lead to the downfall of the old House of Lennox. Probably because of the warring times, by 1390 the Lennoxes must have felt vulnerable at Balloch and they built an additional stronghold, a Castle, on Inchmurrin.

The ruins of Inchmurrin Castle remain visible at the southwest tip of Inchmurrin. For a time the Earls' headquarters was transferred to Inchmurrin Castle and there are a number of documents issued at Inchmurrin, which bear their seal. This has led to a misconception that from 1390 onwards Balloch Castle was completely abandoned and that indeed the stones from it were transferred and used for the building of Inchmurrin Castle. This is not the case. All that happened was that for the 35 remaining years of the ancient Earldom of the Lennox, Balloch was not the Lennox's seat of power - Inchmurrin was. But Balloch Castle remained pretty well intact and for about 20 years after the Partition of the Lennox, Balloch castle remained the primary residence of the Lennox's successors in the Balloch estates, the Darnleys, before they too moved their main residence to Inchmurrin.

The move to Inchmurrin was not of itself significant to the fortunes of the Lennox family, but it more or less coincided with an arranged dynastic marriage that brought catastrophe to the family. Countess Isabella, a daughter of the Earl of Lennox, had married the son of the Duke of Albany. This Duke was not only James I‘s uncle, but also the Regent while James was held captive by the English. The Duke was instrumental in having James' imprisonment extended to 18 years. By the time James returned, the old Duke of Albany had died and Isabella's husband had succeeded to the Dukedom, as Duke Murdoch.

Not unnaturally, James was hell-bent on revenge on anyone who had participated in his imprisonment. The Albany family was his main target, but he lumped in their in-laws, the Lennoxes, just to make sure. Not long after he was crowned King James I at Scone in May 1424, the round up began. As well as 26 others whom he held responsible for his extended imprisonment, Isabella's husband Duke Murdoch, two of her three sons (one escaped to Ireland never to return) and her 79-year-old father, Duncan, Earl of Lennox, were arrested. The 26 others were subsequently freed, but while in residence in Balloch Castle, Isabella learned that her husband, 2 sons and father, the Earl of Lennox, had all been executed at Stirling in July 1425, after a 2 day state show trial, which unfortunately would not be out of place in modern times.

The family was effectively wiped out and Isabella was exiled, or exiled herself, to Inchmurrin. She spent the rest of her life in virtual house arrest on Inchmurrin, dying there about 1460. However, she was not stripped of the Lennox lands by the King, which she could well have been, and Isabella died not only as Duchess of Albany but also as Countess of Lennox.

These executions destroyed the Lennox succession and led to what history has called Partition of the Lennox. The Partition was principally of the lands, because events ensured that the title of Earl of Lennox passed within a couple of generations directly to the person who became James VI of Scotland and James I of the United Kingdom. He and his family had quite enough titles already, and they passed the title around favourites - the current title is one of many belonging to the Duke of Richmond and Gordon who lives at Goodwood in Sussex and has absolutely no connection with the lands of the Lennox.

The legal dispute over the Partition was bitterly fought in the law courts where each of the three separate claimants displayed the sort of greed, avarice and selfishness for which the Scottish (and British) aristocracy remain justly renowned. The legal profession also displayed their customary acquisitiveness, because the case dragged on until 1493. The settlement saw the lands of the Earldom being broken into three parcels, which were acquired by three separate Lennox family descendants.

The area in the immediate vicinity of Balloch passed into the hands of the Darnley Stewarts family, one of whom, Henry Lord Darnley married Mary Queen of Scots in 1565, and became father of James VI of Scotland - who became James I of the United Kingdom of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales in 1603. That Lord Darnley didn't live to see that of course, having been murdered, probably with Mary's connivance, in Kirk o' Field in Edinburgh in February 1567. The Darnley lands included Balloch estate and Balloch Castle. One of the other parcels of Lennox land went to the Haldanes of Gleneagles. It is after these Haldanes that Mill of Haldane is named, and the document defining what properties the Haldanes received in the break-up of the Lennox territory is rich in farm names around Balloch, which we still recognise to day.

On completion of the Partition in 1493, the Darnley family quickly established themselves in Balloch Castle, where they entertained Scottish monarchs and are even said to have added an early tennis court. However, by 1511 it seems that the Darnleys had gradually abandoned Balloch Castle. They transferred their main activities to Inchmurrin Castle, which they used as a hunting lodge from that time onwards, and where they also entertained Scottish monarchs. Balloch Castle and estate continued in the hands of the Darnley's until 1652 when they were sold to Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, who was himself a descendant of the Lennoxes. Little more is heard of the first Balloch Castle. The Colquhouns sold Balloch Estate in 1802 to John Buchanan of Ardoch, but more of that below.

The term “time immemorial” is one much loved by historians. This is partly because it means exactly what it says (so long ago that nobody can remember), unlike much else in history, partly because it allows them to admit that they have no documentary evidence to date an event or activity, and this saves them the often-considerable effort of doing the research to establish a date. “Time immemorial” is the term most frequently used to describe the origins of Balloch's two other points of reference - the Ferry across the Leven, and the Balloch Horse Fair.

Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5