Industry in the Vale of Leven - Page 2

Page 1 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5

As their markets declined in the 1930's, the UTR tried new products and processes to offset the decline and break into new markets. At Dalquhurn small weaving and knitting sections were set up. During the war, Dalquhurn operated under the wartime direction of the English Bleachers Associations, to which the UTR sold their interest after the war. In fact Dalquhurn was largely closed by 1942. After Dalquhurn had changed hands, part of it was let to CF Taylor, worsted spinners, of Yorkshire, who operated there for many years and employed about 200 people.

In 1947, a new UTR subsidiary, Lennox Knitwear, was set up and housed in Dalquhurn. It employed about 300 people at its peak, and lasted slightly longer than the UTR itself, hanging on until 1962, while the UTR was bought over and closed in 1960. Also, Antartex moved into Dalquhurn in the early 1950's before moving to larger premises in the ex-UTR's Alexandria Works in the 1960's. In later times, it housed a number of retail outlets including the Dalquhurn Shop, which was very well known as a convenient source of a wide range of fabrics. Its successor is still operating at Dalquhurn, while MacColls Buses have also recently moved there. They may well be on the move shortly, because at the time of writing the Renton-based Cordale Housing Association has announced a £45 million plan to build 280 houses on the Dalquhurn site.

In 1772, Milton Works was opened on the east bank of the Leven, immediately opposite Levenfield Printworks on the west bank. The company which built it, which now called itself Todd & Shortridge, also owned Levenfield Printworks. Milton Works later became known, as the “Laigh Field”, or Low Field, to distinguish it from Levenbank Works, the “Heigh Field”, or High Field, which was further up the river from Milton. Milton Works dyed yarn, which was then transferred across the river to Levenfield for printing. Because they were adjacent to each other but separated by the River, a ferry ran between the two works. It was so convenient for people who lived in the Jamestown Terraces that it survived, albeit running intermittently, into the 20th century. The “Ferry Steps”, complete with chain ring, are still more or less intact on the towpath on the western bank of the Leven, outside a bricked up gate to what would have been Levenfield Works. Milton Works were initially perched right on the River Bank.

After Milton Terrace had been built in the 1830's, Milton Works was extended behind the Terrace into the ground now occupied by Gilmour & Aitkens' wood yard. The two sites were linked by a tunnel, which ran under the Jamestown - Bonhill Road, and the shop between Milton and Levenbank Terrace. Milton was originally built as a small bleachfield for Levenfield, but after it was bought over by Archibald Orr Ewing in 1850, he considerably expanded it (that is when it extended to behind the Terrace) to handle Turkey red and fancy yarn dyeing. It survived becoming part of the UTR, but it was partially closed in 1911, and fully closed in 1919.

The part of the factory between the road and the river was demolished, and the tunnel boarded up soon after Milton closed - although for about 50 years children used the tunnel as easy access to the river. The site lay derelict for many years. In the 1980's it was landscaped and the tunnel bricked up. Now a riverside walk goes through the old factory site. The part behind the Terraces was, and still is, accessed from Auchencarroch Road. It has served as a sawmill and wood-yard at least since World War 2. Tommy Anderson operated it during and after the war, and a number of German and Italian Prisoners of War worked there, and were housed in huts in the works. Some stayed on after the War.

When Tommy Anderson sold it, it passed through a number of hands, including those of John Lawrence of house building and Rangers FC fame. Wood was delivered by rail via the Jamestown Line and the Milton / Dalmonach branch line right until the line closed in 1964. It was rumoured that the line was only kept open for so long because of Lawrence's influence, but that seems a cast-iron urban myth. Its present owners Gilmour and Aitken have expanded the wood yard, but the boundary walls are those of the old Milton Works.

Watson, Arthur and Co opened Levenbank Works, known as the “Heigh Field” or High Field, because it was further up the Leven than Milton works, in 1784. For a factory, which was to grow so large - it was eventually bigger than the village of Jamestown - its initial purpose was very modest. It was built to do block printing of small items and even as late as the 1840's it was still operating on a very modest basis with about 220 employees. That all changed after 1845 when it was bought by Archibald Orr Ewing. He left Croftengea Works when his brother retired from them in 1845. Archibald was not retiring, however, quite the opposite - he was going to build his own textile business.

In 1845 he founded Archibald Orr Ewing & Co. The first thing it did was to buy Levenbank works and he brought a ready-made management team with him from Croftengea. He completely rebuilt and expanded the works, buying up a lot of the property in Jamestown in the process, and within a few years nothing of the original works survived. About 10 years after he bought Levenbank, the Balloch-Stirling railway line was passing right beside the works, and he quickly built sidings to take advantage of rail transport. Levenbank undertook both Turkey-red dyeing and printing.

In 1897 it became part of the UTR and its role changed to become mainly a dye works, sending on to Alexandria or Cordale cloth which was to be printed, while cloth which was to be finished went to Dalquhurn. Some work continued to be done at Levenbank up until the outbreak of WW2. Then, however, Levenbank became a victualling store for the Admiralty - among the other prized items stored there was Navy Rum for the sailors daily tot. It did not re-open for textile operations after 1945. However, some of the buildings were let out to other smaller companies immediately after the war. These included:

- Franco Signs, makers of neon advertising signs. They were located in a building close to the railway line and the main gate, which was just beside Smith's pub in Main Street Jamestown.

- Wallcraft Paint, as their name suggest made

paints at Levenbank and were located in a building overlooking the north

end of the lade.

- Leddy & Glen had a photograph processing unit.

These companies were there from the late 1940's into the 1950''s.

- There was a cattle market based in the middle of the works. It was accessed via the Dalvait Road gate and operated to the benefit of local farmers for many years.

- Loch Lomond Import Trading Company who dealt in wood, were there for a time in the 1950's.

- Jamestown Concrete made concrete slabs and paving stones well into the 1980's

- Kunz Engineering had a light engineering works also until at least the late 1970's. The building occupied by Kunz was then converted to flats, which are entered from Dalvait Road. This is probably the last Levenbank Works building still standing.

Dalmonach Works were the next to open after Levenbank. They opened in 1785 by John Black & Son. They are located on the east side of the Leven just north of Bonhill Bridge. The original works were, of course, much smaller than what still survived until very recently, but they were burned to the ground. As has been mentioned, fires were quite a common occurrence in most of the Vale bleaching  and dyeing works over the years. The works were rebuilt in 1812 by Henry Bell of the paddle steamer Comet fame, when machine printing with engraved cylinders was introduced.

and dyeing works over the years. The works were rebuilt in 1812 by Henry Bell of the paddle steamer Comet fame, when machine printing with engraved cylinders was introduced.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Dalmonach was an innovative works in terms of technology and education, and was highly regarded by its peers in the Vale. It was for many years regarded by most people in the industry as the most important works in the Vale. There are many examples of its leadership in technology - it was the first works to use a two-colour printer, which it did in 1812. Later Dalmonach had machines capable of printing on cloth 60 inches wide, and printing 16 different colours. These machines were the only ones in Scotland capable of printing so many colours. At its peak it had 28 machines at work, and the works employed more than 800 people.

It passed through a number of owners and name changes in mid century but by 1871, it reverted to James Black & Co., the name it retained until it closed in 1929. Its destiny was sealed in a few months between 1898 and 1899. In July 1898, James Black was floated on the stock market as a public company. The floatation raised £75,000 (compare that with the £500,000 which Argyll Motors raised 8 years later). The money doesn't seem to have been put to any specific use, and we can only assume, therefore, that the then owners were using the floatation as a means of extracting some value from the business for their own benefit. This is, of course, a perfectly legitimate practice, which goes on all the time.

The major risk with a public floatation, however, is that it leaves the company more exposed to being taken over, and this is exactly what happened with Dalmonach. In 1899, the Calico Printers Association, (CPA), was formed in Manchester by 46 British textile companies, 32 English, 14 Scottish. The aim was to use size to protect everyone's commercial interests. The expected benefits from economies of scale and wider market contacts, which the CPA, on paper represented, would considerably increase the founding companies' likely future success. That was the theory anyway. The CPA's floatation value was £6 million, and James Black exchanged their shares for an equivalent value in CPA shares, to become a founding member of the CPA.

The aspirations on which the CPA was founded, proved to be illusory from the outset. Within three years the CPA had lost half of its floatation value of £6 million. The words of an irate shareholder at the third AGM of the CPA cannot be improved upon to describe the situation: “the shareholders have received nothing for the last two years, and the shares have depreciated to the extent of £3,000,000. The position of the Association represents a disaster unparalleled in the commercial annals of Manchester”. The CPA had to act to save itself from going broke, and what it did was exactly what some people in the Vale had warned against when James Black joined it: Because it was dominated by English firms, it gave work to them first.

At Dalmonach between 1906 and 1909, the works were running at much less than full capacity while by 1910, the workforce had been substantially reduced. By this time CPA had already closed a number of other, hitherto successful, operations in the West of Scotland. The works were now in steady decline and finally closed in 1929; another victim of remote management, but by no means the last in the Vale. The CPA was the harbinger of death for Vale textile firms for much of the 20th century, as we will see below.

However, James Black's closure was by no means the end of the Dalmonach site. On the outbreak of the Second World War, like a number of other Vale textile factories, Dalmonach was requisitioned by the government for military use. It served as a barracks for the duration. It housed mainly English regiments, and a number of soldiers who were stationed there married local girls and settled in the Vale after the war. Also after the war, the buildings were put to good use by a number of local organisations that provided useful services and jobs.

These included:

- The Vale fire station - a full time unit in those days - was located there until the new fire station was built in Dumbarton in the late 1950's, when the units were transferred there.

- Paddy Caulfield's sand and quarrying business was based there for many years after the war and his fleet of lorries was garaged there

- J & W Greig wool merchants, whose name could be seen on the side of one of the buildings beside the main road until May 2006, ran a busy operation from the1950's.

- Alan Methven's car repair business was there until 2006 when it relocated to North Street Alexandria.

- Robertson's agricultural supply business which in the summer of 2006 moved to what had been Balagan bus garage

- The second-hand business in Dalmonach School

In the early 2000's there were rumours that Tesco was going to build a superstore on what would have been an ideal site, but the Vale-averse council deemed an oversupply of superstores in the area - presumably they meant Dumbarton and Clydebank since there are none in the Vale - and Tesco has dropped the idea. At the time of writing, spring 2006, plans are well advanced for houses on the site and the remaining businesses have departed.

Demolition is well under way on the site, hastened by wilful fire-raising in some of the buildings adjacent to the Jamestown road. This caused the road to be closed for a few days, and required the immediate demolition of some of the buildings for safety reasons. Unfortunately, most of the site has become a bit of an eyesore and development will be welcomed by most.

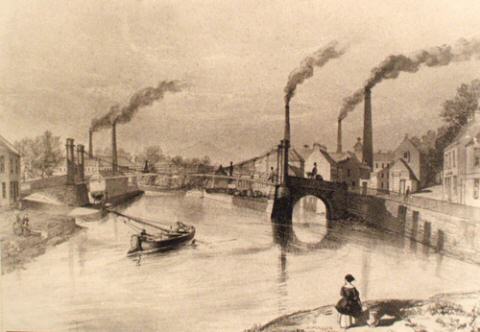

Immediately across the Leven from Dalmonach Works, was Ferryfield Printworks. It was opened in 1785 as a smallish Printworks. During the 19th century it underwent a number of changes of ownership and expanded to the point where it was at one time employing more than 400 people. However, by the early 20th Century it was clear that it would not survive on its own. It chose to join the CPA in 1906, and by then it must have been obvious to its owners what Ferryfield's fate would be whatever action they took.

Ferryfield Works (left) and the Bawbee Brig

with Dalmonach

Works on the right

Perhaps to them, the CPA offered a few more years of operation. Perhaps it did, but by 1909, CPA had closed down 40% of its productive capacity, and CPA closed Ferryfield for good in 1915. It was the first of the major textile works in the Vale to close in the 20th Century, and unfortunately, its closure represented the shape of things to come. It lay empty until 1925 when the buildings were demolished.

Our Lady and St Mark's RC Church was built on part of the site in 1926, and about the same time Saint Mary's school was built at the south-west side of the old works. Apart from a car-repair business in a Nissen hut, more or less adjacent to Saint Mary's, the rest of the site lay cleared, but empty, for 70 years until a private housing development was built on the remaining land on the site.

Page 1 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5