Loch Lomond Villages - East

Inversnaid - Rowardennan - Sallochy - Balmaha - Milton of Buchanan

Buchanan Smiddy - Drymen - Croftamie - Kilmaronock - Gartocharn - Ballagan

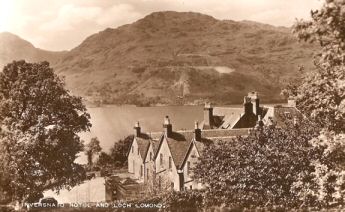

INVERSNAID

“Mouth of the needle stream” - the Snaid burn being called after a snathad, or needle in Gaelic, which is good description of it as it comes through the very narrow gorge, and over the gorge waterfall, immediately before flowing into the Loch at Inversnaid. The hotel and hamlet on the east side of Loch Lomond lie at the very heart of Rob Roy country. His estate of Craigrostan, or Craigroyston as it is now spelled, was centred nearby in the foothills of the north side of Ben Lomond, and included the area of Inversnaid.

In 1713, the Duke of Montrose's men burnt his house at Craigroston as part of his on-going feud with Rob Roy. In October 1715, after the Jacobite rebellion had got under way, Rob Roy, who actually was a staunch Jacobite, launched an attack from his base at Craigrostan, ostensibly on the Hanoverian government. Although the Jacobite leaders probably believed that it had a military content, such as capturing Dumbarton Castle, being Rob Roy, this raid really had a material objective - stealing cattle and anything else of value. The chance for material gain at the expense of his two most hated opponents, the Colquhouns and Montrose, was just too good an opportunity to pass up. That both of these families were amongst the government's most prominent local supporters was an additional bonus.

With about 200 men Rob Roy sailed out from Inversnaid in October 1715, down the Loch, on a sortie which became known as the Loch Lomond Raid. The government's counter measure of a few days later was rather grandly called the Loch Lomond Expedition. Suffice to say, that his old enemies the Colquhouns and the Grahams bore the brunt of his theft. At the first sign of potential resistance in the Vale of Leven, he legged it back to his Lochside stronghold.

A few days later a motley collection of government forces and local militia headed up the Leven from Dumbarton, and sailed and marched up the west shore of the Loch. This early version of a combined operations task force, which was the only naval action on inland water conducted by British forces in modern times, pitched up just off Inversnaid. Seeing only a few women and children about the houses on the shore, the government forces felt that it was safe to attack. A couple of cannon balls were lobbed into Rob Roy's settlement, destroying the roof of one house and bringing out an old women who rained Gaelic curses on them. This was the only response, and the commanders felt confident enough against women and children to land a small party of soldiers.

They marched up the hill to the Garrison of Inversnaid, roundly denounced Rob Roy in word if not deed, got back to their boats without delay, and sailed home. When they got back to Dumbarton, they immediately published a version of these events, which was almost unique in the annals of military communiqués in being entirely truthful. It broadcast news of the victory over Rob Roy, which was true because he had disappeared offering no resistance.

The amazing thing was that no one was killed or even seriously injured, and that everyone seems to have got more or less what they wanted out of it - except the Colquhouns and Grahams, who never saw their cattle or goods again, and no one seems to have been bothered too much about them. Rob Roy made another raid about six weeks later, but that was definitely just theft - he sacked Luss, robbing the parish minister in the process - and no government troops set out after him that time.

There is a cave about 1 mile north of Inversnaid in which Rob Roy is supposed to have hidden, but that falls into the category of “rural myth”. Its just possible, however, that it is the cave in which Robert the Bruce sheltered when he was on the run on Loch Lomondside.

At the top of the hill and close to the Inversnaid - Aberfoyle road lies the already mentioned Garrison of Inversnaid. There is disagreement about exactly when it was decided to build it - dates range from 1703 to 1713, but building started in 1718 and it was garrisoned by about 1720. It did see action occasionally - Rob Roy set fire to it, and his nephew captured it during the 1745 Uprising.

After the '45, things were a lot quieter, and the garrison was engaged mainly in road building. It is said that General James Wolfe - later famous for capturing Quebec - was stationed there about 1746. An idea of its size may be gained from Ruthven barracks, which are quite visible from the A9, south of Inverness, and were built at the same time as Inversnaid. The arrest in 1753 of Rob Og, Rob Roy's son, at a fair at Gartmore, is the only known act of law enforcement carried out by troops stationed at the Garrison. He was wanted for the abduction and forced marriage of a widow, and was hanged for these crimes in 1754, so these troops carried out a serious duty.

It was last garrisoned in the mid 1790's, and when the poets William and Dorothy Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge visited Inversnaid in 1803 they found that the barracks and outer wall appeared intact, although they didn't at first know what it was. Gradually it just fell into ruin and there is little left to see of it now in the attractive little hamlet of the Garrison.

In 1803 there was only a landing place and the ferry house at Inversnaid, but both Wordsworth and Coleridge were much taken by the beauty of the ferryman's sister - Wordsworth wrote a poem to her “To the Highland Girl of Inversnaid” and that laid the foundation of Inversnaid's tourist industry.

The ferry to the western shore still operates and has been on the go for over 200 years. It was the coming of Loch steamers which actually kicked the tourist industry off, and when the railway eventually came to Callander in 1858 and Aberfoyle in 1882 a grand Loch Lomond and Trossachs tour by train, steamers coach and horses and then train again, became not only possible but very popular. It's hard to believe now, but four-in-hand horse-drawn open coaches climbed the hill from Inversnaid Pier en route to Stronachlachar (steamer to Trossachs Pier) and on to Callander or Aberfoyle railway station. These coaches had the distinction of providing the last horse-drawn coach service in Scotland - they only stopped running in 1937.

The pier was built about 1847, and the hotel sometime before that. Even as late as the 1960's some of the supplies for the Hotel were delivered from Balloch by the Loch steamer, and the pier never closed to the steamer, although it did take advantage of the piers improvement program. However, Inversnaid was not behind the times - in fact it was the first place on the Loch to have electricity when the Hotel started to generate its own in 1900.

The hotel was always a great favourite with the boatmen on the Loch - fishermen and cruisers alike. Its heyday as a Loch watering hotel was probably in the period 1960 - 90, under George Buchan, whose family farmed at Garrison. It is now owned by Loch and Glens coach touring company, has been much extended and is busier than ever.

It prospers from the bus parties it caters for, residents of its bunkhouse, walkers on the West Highland way and water users. The harbour, which has been dredged, is the berth for the Inversnaid - Inveruglas ferry.

ROWARDENNAN

An alternative to Hunter's origin of the name is “Eunan's high promontory”. Whoever Eunan was, it's a pretty good description of the area around Rowardennan Hotel. Rowardennan is the end of the road on the east side of Loch Lomond, although the West Highland way continues northward to Inversnaid (a mere 7 miles) and beyond.

The hamlet has a Victorian / Edwardian look to it since the Hotel, the Youth Hostel and a couple of shooting lodges look as if they date from that period, which some of them do. As an overall impression it is quite deceptive, however, since the Hotel has evolved from an old Inn, dating from around 1696, and Rowardennan - Inverbeg has been an important east-west crossing on the Loch since time immemorial. A ferry still operates in the summer months from Rowardennan to Inverbeg.

Also, Rowardennan was on an old droving route, particularly when Crieff Tryst was in its heyday, before being replaced by Falkirk about 1770. Cattle were swum across the Loch from Inverbeg, led by specially trained cattle, which were kept at Inverbeg for that purpose. Being in Rob Roy country, Rowardennan naturally has a few tales to tell. One of them may be in the process of being uncovered right now by an archaeological excavation being carried out about half a mile north of the hotel. It is suggested that this ruined farmstead, which lies a couple of hundred feet above the West Highland Way, may have been home to Rob Roy at one time.

Also, Rowardennan was on an old droving route, particularly when Crieff Tryst was in its heyday, before being replaced by Falkirk about 1770. Cattle were swum across the Loch from Inverbeg, led by specially trained cattle, which were kept at Inverbeg for that purpose. Being in Rob Roy country, Rowardennan naturally has a few tales to tell. One of them may be in the process of being uncovered right now by an archaeological excavation being carried out about half a mile north of the hotel. It is suggested that this ruined farmstead, which lies a couple of hundred feet above the West Highland Way, may have been home to Rob Roy at one time.

The Hotel has a much darker tale to tell. In December 1750 the Hotel was where one of Rob Roy's sons, Rob Og, forcibly married and bedded a young widow, whom a party of McGregors had forcibly abducted from her home at Edinbellie, which is just outside Balfron. Rob Roy himself was long dead by then, of course, and so was the practice of forced marriages.

The motivation was, as ever with Rob Roy's family, money. The widow, Jean Kay, was thought to be reasonably rich for the day. There was no way the McGregors were going to get away with something like this, and both Rob Og and his brother James, who probably hatched up the plan, became fugitives. Rob Og, after hiding out in Argyllshire and then France, was caught at Gartmore in 1753, by soldiers from Garrison of Inversnaid (just about the only act of law enforcement in which they were known to be involved). Rob Og was hanged in February 1754 for this crime, aged 37.

Since the mid 19th century, the main attraction of Rowardennan is as the starting point for climbing Ben Lomond, which towers 3,192 feet above. In those days most tourists would arrive by steamer at the pier, which was built about 1850, and a great many of them would hire a pony and a guide at Rowardennan and ride to the top of the Ben on the pony.

Since the mid 19th century, the main attraction of Rowardennan is as the starting point for climbing Ben Lomond, which towers 3,192 feet above. In those days most tourists would arrive by steamer at the pier, which was built about 1850, and a great many of them would hire a pony and a guide at Rowardennan and ride to the top of the Ben on the pony.

Nowadays they walk in on the West Highland Way, or come by car on the east shore road, and have to park there, because the road finishes at the car park at Rowardennan Pier. The pier, like the one at Inversnaid, was never closed to steamers while they sailed on the Loch, and although changed a little in shape by the refurbishment program, of 1978 - 83, it can still handle any cruise boat operating on the Loch.

There are now a number of starting points for the climb, all basically leading off from the West Highland Way, but the most popular now lead off from the pier car park. On the north side of the car park on an appropriately beautiful site looking north up the Loch and onto Ben Lomond, is a sculpture dedicated in 1995 to those who gave their lives in the service of their country.

From the 1920's to 60's Rowardennan Hotel was a favourite destination for a weekend visit by the boats and sailors of the Balloch flotilla. They would sail up on a Friday evening and old highland and island licencing hours (i.e. none) were kept until their Sunday evening departure. Times change, of course, but Rowardennan Hotel has remained a favourite Loch side hotel all the year round, as much with West Highland Way walkers as with boating people and the residents of the adjoining caravan site.

An old shooting lodge was acquired by the Scottish Youth Hostels Association about half a mile north of the Hotel, and with 75 beds this continues to be one of the busiest in Scotland. There is even a Ben hill race from Rowardennan for which the winning time, up and down, is usually less than one hour. Just south of Rowardennan, Glasgow University's Research and Field Station, which was the first of its kind when it was started on the Loch side in 1938, has been located since 1964.

Click on above images to view larger versions.

SALLOCHY

The area called Sallochy is situated about half-way between Rowardennan and Balmaha, just south of the Dubh Loch. It stretches from Ross Point south along the Loch and east up onto the hillside. Apart from the Loch shore, woodland, much of it oak, is now the area’s main feature. Naturally enough the woods also feature in Sallochy’s early history. Trees from Sallochy, as well as from nearby Inchcailloch and Luss, were felled to build ships for King James IV’s navy in 1494-95 as he prepared a punitive expedition to sail against the rebellious Lord of the Isles. The ships were built at Dumbarton and the timbers were sailed down the Loch and then the Leven to the ship-yard at Dumbarton.

Over the years Sallochy has acquired a number of spellings of its name. According to the JB Johnston's "Place Names of Stirlingshire" (2nd edition 1904), Sallachy, as he spelled it, dates from about 1350 and is derived from the Gaelic "salach" meaning dirty, which is hardly what you would expect or how you would describe it to-day.

By 1833, Woods' map was spelling it Salachy. The map shows 3/4 houses on the east side of the Balmaha – Rowardennan road, and these are probably the houses whose ruins are re-appeared after recent forestry clearing and are shown in the Google photos.

The most informative source in that area is, as usual, John Guthrie Smith's "Strathendrick & Its Inhabitants from Early Times" (1896). In his section on Buchanan Parish, Guthrie Smith tells how the Reverend Robert McFarlane who was minister at Buchanan 1707 – 1758, introduced a schoolmaster into the "highland" part of the Parish i.e. all of it north of Balmaha. The school-master taught school-children at two locations, Inversnaid on the north side of Ben Lomond and Sallachie, as he spelled it, on the south side. These are about 12 miles apart and separated by rough mountainous country, which sheltered Rob Roy McGregor in McFarlane's early years, so journeying from Inversnaid to Sallochy on what would only have been a very rough drover’s or more likely cattle-stealer’s track, must have been a struggle for the school master, who taught at each location alternately. The schoolmaster's house was at Inversnaid, and there is no mention of any school building at Sallochy, so someone's house or byre probably served as a temporary school-room.

It is also known that the school-master in 1729 was George Moir and he taught children the catechism on Sunday afternoons. Religious services were held at Sallochy, but again there is no suggestion of a church building. Services would have been held either in a house or outdoors, weather permitting, which was common enough around the Lochside at that time.

As if the terrain wasn’t enough of a problem, there were also the McGregors and Rob Roy in particular to take into consideration. Rob Roy was a leading Jacobite and no friend of the authority represented by the Church of Scotland, so it was not unreasonable to expect that he might disrupt the work of both minister and school-master – he certainly caused plenty of mayhem further south at Drymen and the Strathendrick area generally. However, nobody seems to have disturbed the teaching and preaching at either Inversnaid or Sallochy.

In 1759 it is recorded that there were 2 families living at Salachi, but there were 262 people residing between the Pass of Balmaha and Rowardennan, and it was them that the school and church services at Sallochy would have served – a substantial enough population at the time.

A few more houses seem to have been added by the mid 19th century, but Sallochy was never more than a wee clachan nestling between the hillside and the Loch, its inhabitants working on the land and in the woods for the local farmer or landowner. It is a fair bet that in spite of its beautiful location, life would have been pretty hard. The present houses probably mostly date from the mid-19th century when the older houses, to-day's ruins, were vacated and then subsumed by vegetation and 20th century forestry.

Some 20th century additions have appeared. There is the Glasgow University Research and Field Station which moved to its present location beside the West Highland Way at the base of Ross Point in 1964. It had originally been established in the 1930’s at Auchentillich Bay just north of Arden on the other side of the Loch to study Loch Lomond. Many people remember the University’s very modest hut at Auchentillich and can’t help but be impressed when comparing that with the present buildings at Sallochy to say nothing of the range of educational activities which take place there. The Centre is not visible from the road and most of its buildings can’t be seen from the Loch either. A fine Alpine or Scandinavian structure is visible from the Loch, but it blends in very well with its woodland setting.

There is a Forestry car-park at Sallochy sitting astride the West Highland Way, from which a number of walks branch out. You can walk stretches of the Way in either direction, the section just north of Sallochy offering a range of differing settings. Or you can take the shortish walk out to Ross Point through native woodland. If you are extremely lucky, you might just catch sight of a capercaillie which are said to frequent these woods, but you would have to be very lucky. Alternately you can go eastward into the old woodland on the other side of the Rowardennan – Balmaha road. When the walk is over you can sit on the sandy beach, cool your feet in the Loch and just enjoy the scenery all around you.

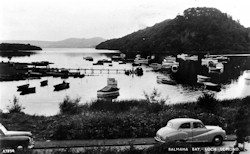

BALMAHA

There are two possible derivations of Balmaha: “Bal maitheas” meaning town of mercy or the goodness of God (one of the Celtic towns of refuge for the shelter of fugitives under the protection of the church), or “St Maha's place”. This derivation of the name seems to be gaining increasing credence, perhaps because of St Maha's well nearby.

There are two possible derivations of Balmaha: “Bal maitheas” meaning town of mercy or the goodness of God (one of the Celtic towns of refuge for the shelter of fugitives under the protection of the church), or “St Maha's place”. This derivation of the name seems to be gaining increasing credence, perhaps because of St Maha's well nearby.

Balmaha lies on the Lochside immediately opposite Inchcailloch, about 4 miles from Drymen, and the Highland Fault passes through the village. Balmaha is on the southern edge of Rob Roy country and he passed through it on his journeys to the Lowlands, and particularly on forays to annoy his neighbour, the Duke of Montrose. The Pass of Balmaha he would have used is not the present one, but one to the east of it over the shoulder of the Conic Hill.

For about 50 years until the 1920's, the Turnbull's Millburn Pyroligneous Works of Alexandria, had a factory right in the middle of Balmaha, the Liquor Works as the locals called it. It was located just about the western side of the present car park, making chemicals for the textile factories in the Vale of Leven. In the early days the chemicals were taken down to the Vale by boat from Balmaha, although latterly they went by lorry. This works consumed about 700 tons of wood a year, nearly all of it grown locally on the Montrose estates.

For about 50 years until the 1920's, the Turnbull's Millburn Pyroligneous Works of Alexandria, had a factory right in the middle of Balmaha, the Liquor Works as the locals called it. It was located just about the western side of the present car park, making chemicals for the textile factories in the Vale of Leven. In the early days the chemicals were taken down to the Vale by boat from Balmaha, although latterly they went by lorry. This works consumed about 700 tons of wood a year, nearly all of it grown locally on the Montrose estates.

Balmaha's more recent economy depends largely on tourism. Its village pub, The Oak Tree, is a popular stop with walkers on the West Highland Way, which passes through the village, and of course with the boating fraternity on the Loch. One of the oldest boatyards on the Loch is McFarlane's of Balmaha, which performs many functions. As well as slipping and maintaining boats, it is a base where anglers can get their catches officially recorded.

Balmaha's more recent economy depends largely on tourism. Its village pub, The Oak Tree, is a popular stop with walkers on the West Highland Way, which passes through the village, and of course with the boating fraternity on the Loch. One of the oldest boatyards on the Loch is McFarlane's of Balmaha, which performs many functions. As well as slipping and maintaining boats, it is a base where anglers can get their catches officially recorded.

Its main claim to fame is that it runs one of the very few inland mail boats in the UK, which delivers the Royal Mail each day to the inhabited islands of the Loch. These attractive wooden boats also carry passengers for a cruise amongst the islands. It was at Balmaha on 6th October 1980, that Lord Mansfield, Minister of State at the Scottish Office, declared the West Highland Way officially open.

Click on above images to view larger versions.

MILTON OF BUCHANAN

The Buchanan family were the most prominent landowners on the southeastern banks of Loch Lomond from at least 1231 until 1682, when the main male line became extinct and the Buchanans became very short of money. They had to sell the estate to the third Marquis of Montrose, who was subsequently elevated to become the first Duke of Montrose in 1707 for his role in the Act of Union. The Buchanans were therefore the predominant family in the area when place names were being allocated at the beginnings of modern history.

Naturally enough, they gave their name to a number of places. The parish of Buchanan was one of them. It was formed in 1621 from the union of the ancient parish of Inchcailloch and parts of Luss parish, which were nearer the eastern shore of the Loch. The parish church of Buchanan, located at what became Milton of Buchanan, was therefore the religious and administrative centre of the parish.

Although virtually empty of people - not least because the boundary runs right up the middle of the Loch, from the mouth of the Endrick to Island Vow - it's a lot bigger than might be expected, covering as it does most of the eastern side of the Loch. Also, it contains many of the most famous places on the Loch - Ben Lomond, Balmaha, Rowardennan, Inversnaid and Rob Roy's estate of Craigroyston (in Rob Roy's time it was known as Craigrostan).

Loch Arklet and a number of the islands such as Clairinch, Inchcailloch, Inchfad, Inchcruin, Buccinch and the Ross Isles also lie in the Parish of Buchanan. Buchanan Parish Church, in Milton of Buchanan is about 2.5 miles from Drymen on the Balmaha road. A private Buchanan family chapel had been there since before the creation of the Parish, when it became the “de facto” parish church.

The present Church site was first built on about 1770, although the church itself dates in the most part from 1828, when major repairs took place. The churchyard still serves as the local burial ground, and contains graves of servicemen from the Second World War who died when in the nearby Buchanan Castle, which was a military hospital for the duration. The local primary school is adjacent to the church.

There were two mills in the hamlet - hence the name. One of them, right on the bend in the road in the centre of the village, has been very effectively rebuilt as a private house quite recently, and incorporating the grindstones, it leaves no doubt as to its original purpose. It is possible to access the West Highland Way from Milton of Buchanan, avoiding the boring stretch through Garadhban Forest, and replacing it with fine views over the Loch and an open approach to the southeastern slopes of the Conic Hill.

BUCHANAN SMIDDY

This hamlet, which lies a mile or so north of Drymen, on the Drymen - Balmaha road was built by the Duke of Montrose in the early 19th century. It initially housed workers on his estate. It also housed the estate's blacksmith's shop, hence the name of the hamlet. The smiddy, which has been closed for many years, is easily identified in the row of two-storey houses.

DRYMEN

Drymen's name derives from the Gaelic for “on the ridge” which remains a pretty apt description for Drymen village to day. It is an ancient community, being both a village and a parish, and its first documented mention is in a charter of 1238. Also, Drymen has the clear claim in the whole Loch Lomond area to the first record of the building of houses for ordinary people. In 1440 the widowed Isabella, Countess of Lennox, by now living on Inchmurrin, gave permission for the building of a tenement of houses and a yard, adjoining the north side of the Kirk yard in Drymen.

The earliest landowners in the area were the Drummonds and the Buchanans, but the Grahams - in the form of the first Marquis of Montrose, who was raised to a Dukedom in 1707 - bought the Buchanan estate in 1682. They came to live in old Buchanan Castle, and the management of their considerable estates was run from there. After a shaky start in the Montrose - Rob Roy feud, the business generated by the Montrose estate did bring commercial benefit to Drymen, and this gradually grew over a couple of centuries. However, in 1700 Drymen was already a gateway into the wilder southern central Highlands, the lands of McGregor in particular.

The McGregors were cattlemen and came and went through Drymen in the course of their trade. Up until this time, most of their raiding and stealing had been directed at the western shores of Loch Lomond, where the Colquhouns were their enemies of choice. They seem to have got on reasonably well with the Buchanans, although they did undoubtedly do a bit of cattle stealing and operated blackmail in the lands of Buchanan and Menteith, and beyond.

They were frequent visitors to Drymen and made use of its many hostelries - although it's a bit unlikely that Rob Roy was a regular in the Clachan Inn as some claim, even if it is the oldest pub in Scotland. It got its licence in 1734, the year of Rob Roy's death at Balquidder, where he had been quietly passing his twilight years. However, there were plenty of other hostelries in Drymen in his day, which he no doubt visited.

Almost from Montrose's arrival in the area, Rob Roy and he became sworn enemies. Their differences seem to have centred on money for cattle, which Montrose says Rob Roy stole from him. Not even Rob Roy disputed that money disappeared, but he said that he too was a victim of theft and he would repay the Marquis when he could. The dispute quickly got a life of its own, with Montrose emerging as an aggressive bully with no judgement, whose behaviour made Rob Roy into a “People's Hero”, while history has treated Montrose with the contempt it has reserved for the Scottish aristocracy of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Almost from Montrose's arrival in the area, Rob Roy and he became sworn enemies. Their differences seem to have centred on money for cattle, which Montrose says Rob Roy stole from him. Not even Rob Roy disputed that money disappeared, but he said that he too was a victim of theft and he would repay the Marquis when he could. The dispute quickly got a life of its own, with Montrose emerging as an aggressive bully with no judgement, whose behaviour made Rob Roy into a “People's Hero”, while history has treated Montrose with the contempt it has reserved for the Scottish aristocracy of the 18th and 19th centuries.

For Rob Roy the feud became a labour of love in which he lost no opportunity to make a complete fool of his more powerful rival. Many of the skirmishes in the feud actually took place in Drymen. Perhaps the best known of them was the abduction of the Duke's factor in 1716, which happened only a few miles away. Rob Roy was a Jacobite, and when the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion took place, Rob Roy led an armed band into Drymen and proclaimed for the Old Pretender. While they were at it, they also destroyed the gauger's excise book, which was a direct attack on the government's hated attempt to tax whisky distillation.

Both of these acts were humiliating for Montrose who not only lost money, but also was made to look weak. As a result of these actions, troops were based in Drymen, but this was very unpopular because they were billeted on people without their consent.

Rob Roy followed these acts up with attacks on the Duke's personal property. In 1717, he firstly raided the Duke's enclosed park at Buchanan Castle and carried away his best cattle, and shortly afterwards he raided the mill at Milton of Buchanan and carried off milled grain. Although nearly everyone in the area was a tenant of the Duke, they were unwilling to raise a hand to help him. This was no doubt partly because they felt intimidated by the McGregors, but it was even more because they favoured Rob Roy much more than they did the Duke of Montrose. History is virtually unanimous in agreeing with them.

Through all that period Drymen prospered, mainly because it lay at an important cross roads. A number of old drove roads passed through Drymen, as did the Dumbarton - Stirling military road, which was slowly built between 1770 and 84. A good indication of the increased activity on the roads around Drymen at the time is that the old Drymen Bridge was built about 1765. It replaced a ferry dating from the early 1500's, which had crossed the Endrick at about the same spot.

From about 1770, when Falkirk Tryst started to become Scotland's premier cattle market, Drymen was a favourite overnight stopping point for drovers. Not only were many pubs and inns catering to the drovers, but there was ample grass in what is now the Square and in fields just to the north of the village in which the cattle could graze.

For a time the very attractive village green hosted a market, and was known as Market Square. A number of the present buildings in Drymen also date from then. The present Church of Scotland was built in 1771, and although it's a striking white building now, for the first 190 years of its existence it retained its original red sandstone colour, only being painted white in 1961. The church underwent a maintenance and improvement program in 2010/2011.

For a time the very attractive village green hosted a market, and was known as Market Square. A number of the present buildings in Drymen also date from then. The present Church of Scotland was built in 1771, and although it's a striking white building now, for the first 190 years of its existence it retained its original red sandstone colour, only being painted white in 1961. The church underwent a maintenance and improvement program in 2010/2011.

The Winnock and the Buchanan Arms Hotels both date from the late 18th century and have witnessed many a tale over the years. Indeed, for many years Drymen most frequently came up in conversation in the Vale, in the phrase “Drymen Dancing”. These Saturday night dances in the Winnock were a regular feature of many a Valeman's (and Valewoman's) Saturday night from the 1930's to the 1960's. The finale was the rush for the last bus to Balloch from Drymen Square, stopping only at Gartocharn for the removal to the police cells of any miscreants.

That sort of social whirl wouldn't have been out of place in the 19th century Drymen, when there were seven pubs and inns around the Square and in the Main street - the Clachan and Winnock survive on the Square as does the Buchanan Arms on the Main Street. The Plough, parts of which dated from 1758, survived until 2001. By then it had been called the Salmon Leap for about 30 years, and was famed for many years as the venue for Billy Connolly's birthday party.

A number of other restaurants and tearooms such as the Anvil have proved worthy successors, making Drymen an ideal destination for an evening (or lunch-time) out. Many of the fine villas in Drymen date from the late Victorian - Edwardian period, and apart from that, for the early part of the twentieth century, the character of Drymen barely changed. It was a largely farming community with no industry and with the railway line just far enough away to be useful in transporting goods, but not intrusive in bringing in people, particularly commuters.

A number of other restaurants and tearooms such as the Anvil have proved worthy successors, making Drymen an ideal destination for an evening (or lunch-time) out. Many of the fine villas in Drymen date from the late Victorian - Edwardian period, and apart from that, for the early part of the twentieth century, the character of Drymen barely changed. It was a largely farming community with no industry and with the railway line just far enough away to be useful in transporting goods, but not intrusive in bringing in people, particularly commuters.

The First World War made the same impact as in other similar rural villages - young men went off to fight, and many never returned. The War Memorial in Drymen, however, has one distinction. It is one of the very few War Memorials anywhere in the UK to have been unveiled by Earl Haig, the commander of British forces in France in World War One. Haig was hugely unpopular after the War and kept a low profile, not venturing much into public view outside the Borders, where he had his home, and where he also unveiled a few war Memorials. He performed the task in Drymen as a “favour” to his pal, the Duke of Montrose.

In 1928 the present Drymen Bridge was constructed to replace the one of 1765. In 1936 the Duke of Montrose opened a golf course on the parkland of Buchanan Castle. The clubhouse made use of a surviving part of what is now called Buchanan Old House. This is part of the old Buchanan Castle, which burned down in 1852. The present Buchanan Castle replaced it in 1854, but that in turn had its roof removed in 1955 so that the Montroses did not have to pay local rates on it. Part of what is now the golf course had been laid out as a race course and gallops by a horse-racing Duke, whose horse Sefton won the Derby in 1878.

In 1928 the present Drymen Bridge was constructed to replace the one of 1765. In 1936 the Duke of Montrose opened a golf course on the parkland of Buchanan Castle. The clubhouse made use of a surviving part of what is now called Buchanan Old House. This is part of the old Buchanan Castle, which burned down in 1852. The present Buchanan Castle replaced it in 1854, but that in turn had its roof removed in 1955 so that the Montroses did not have to pay local rates on it. Part of what is now the golf course had been laid out as a race course and gallops by a horse-racing Duke, whose horse Sefton won the Derby in 1878.

In the Second World War, Drymen had a slightly higher profile than in the First, because Buchanan Castle was used as military hospital for the duration. When Rudolph Hess, Adolph Hitler's deputy Fuhrer, flew to Scotland in May 1941 intending to see the Duke of Hamilton with a view to ending the war, which at that stage was mainly between Britain and Germany, he ended up instead spending the night at the family seat of another Scottish Duke, in a guarded ward of the military hospital.

Drymen was always a farming village, and has retained that character until the last 20 years or so. Now an increasing number of commuters from the central belt have found the village a very congenial place to stay. It remains to be seen what impact the decision of the hapless National Park Authority to allow a substantial housing development on the outskirts of the village will have.

Click on above images to view larger versions.

CROFTAMIE

While many of the estates, farms and houses in and around the present-day village of Croftamie go back hundreds of years, the name “Croftamie” goes back little further than the 1840’s although there are, as we shall see, some references to an area called “Croftamy” before that. Even when the Forth & Clyde Junction Railway (&C) from Balloch to Stirling railway line reached the village in 1857, the railway company called the station Drymen Station, rather than Croftamie. That of itself was not unusual with the F&C’s naming of stations - of all the stations on the line, only Jamestown is actually in the village after which it is called - but it does suggest that Croftamie was not of any great size even by the 1850s.

A Balloch-Stirling steam train heading into Croftamie station in the early 1900s

Prior to that, there is a reference in 1823 on a Kilmaronock Parish map to an area called Craftamy, close to what is now the village. Some church records of that time also mention a Craftamy. However, the New Statistical Account of Scotland published in 1839, says that in the whole of Kilmaronock parish “not even four dwelling houses in it are closely continuous”. Just two years later however, in 1841, the spelling “Croftamie” makes its first appearance on the very first national Census of 1841, as the extract below from the Census, sent to us by Ron Aitken, shows.

The name then passed into general use because the Imperial Gazetteer of Scotland, published in the late 1850's, does make reference to “Croftamie”, (although the 1884 Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland still calls it Drymen Station.)

The name then passed into general use because the Imperial Gazetteer of Scotland, published in the late 1850's, does make reference to “Croftamie”, (although the 1884 Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland still calls it Drymen Station.)

In spite of its comparatively recent origin, then, there is no authoritative definition of the name Croftamie. Although the village is comparatively new, farms, houses and lands in the area are very well established, being steeped in history. In the middle ages the Earls of Lennox had one of their family seats - and also their gallows hill at nearby Catter Hill – where Catter House now stands.

In the early 1500's, an Earl of Lennox granted some Catter land to a Buchanan, on the condition that he kept a ferry running across the Endrick. For many years Catter House was the residence of the Duke of Montrose's factor. Other farm names have connections with the early middle ages. For example, the name Spittal indicates that its lands were once owned by the Order of Knights Hospitalers - one of the military / religious orders dating from the time of the Crusades. There are ruins of a building close to the Endrick, which probably belonged to the Order.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, drove roads were passing close to Croftamie. The Drymen - Glasgow road over the Stockiemuir would also be busy enough for the times. After 1770 when Falkirk Tryst became the principle Scottish autumn cattle market, the main drove road from the west passed over Cameron Muir and down into Killearn (this was still before the days of the toll at Finnich).

In 1819 the first of a number of rural industries is known to have started in what became the village of Croftamie. This was a joiner’s shop. A sawmill, which was powered by the water of the Catter Burn, soon followed the joinery. The sawmill was started by a Mr Edmonds and quickly became a success, employing over 30 men. The Edmonds family features prominently on the first of the two 1841 Census pages which are displayed, when Mr John Edmonds was 45. Mr Edmonds built Edmonds Terrace to accommodate his employees. Both of these enterprises proved long term successes - the sawmill worked on until 1937, when it was destroyed by fire. The joiners shop was still working until the Second World War, when it was converted to the Red House tea room. Later this became the Red House lounge, and is now the Wayfarers, which still incorporates some of the stone-built joiners shop.

This is an image of Croftamie with the Red House on the right taken from an old, 1950s postcard.

This is an image of Croftamie with the Red House on the right taken from an old, 1950s postcard.

Note that even then they were still referring to it as "Drymen Station".

Close to the sawmill and joiners shop, in what is now the car park of the Wayfarers, men from Glasgow came out each summer to make wooden clogs. This is the origin of the nickname for that area of “Cluggers”. Close by, too, from about 1900 was a small workshop in which was made a boot blacking called Pixol, and the Heather brand shoe polish.

On the other side of the Catter, just off the Glasgow road, a quarry was opened about 1850, and this was soon the largest employer in the area, employing about 60 men at one time. The stone was used to build a number of local houses, including Pirniehall in 1896. The quarry closed in the early 1900's.

Lint and meal mills also operated beside the Catter in the village - the meal mill operated right into the 1950's. With all this farming, quarrying and wood based business going on, carting was obviously active, and so was the village smiddy. It is reckoned that as many as 8 blacksmiths were employed in the Smiddy at its peak.

When the railway arrived at Croftamie in 1856, it came into the midst of a thriving, busy rural community whose main businesses were already in place, and where tenements, houses and the local inn (now the Croftamie Farm) had stood for a number of years. The village hardly grew up around the station, but it became a sort of focal point and the village expanded from it.

The farmer of the Spittal Farm (or Spittle as it is spelled on page 2 of the 1841 Census) had to pay a price for the arrival of the railway. In the 1850’s the farm buildings stood astride the intended track of the new rail line, down towards the Endrick, east of the station. The buildings had to be demolished and replaced by the present Spittal farm buildings adjacent to the station.

There were a few components of a typical village missing. For one thing, there was not, nor ever has been, a church. Kilmaronock Parish church is the parish church for the village, and people were expected to walk to it, summer and winter. Nor was there a village school. Although there was one nearby at Finnich Toll, this was in both a different parish, and a different county, which at that time were important considerations.

Croftamie village children were required to make their way to Kilmaronock School, which lay about half a mile west of the Parish Church on the Balloch - Drymen road. This matter was rectified in 1907 when Croftamie Primary School was opened and the school at Kilmaronock closed. However, Croftamie Primary School was itself closed in 1996.

The arrival of the railway was hardly earth shattering for Croftamie, although it did provide occasional light diversions. The Duke of Montrose negotiated an entitlement to a first class carriage for his personal use, and when he was in residence at Buchanan Castle it was kept in one of the sidings at Croftamie. The various exotic visitors to Buchanan Castle, such as the crown Prince of Japan and the Shah of Persia usually arrived at the station in this carriage, before transferring to a coach for the last few miles. Locals therefore got a chance to see these comings and goings.

For every eastern potentate, however, there were a few thousand cows, because much of the traffic on the Balloch - Stirling line right up to the Second World War was agricultural in nature. However, the stone quarry at Croftamie as well as another couple closer to Drymen, undoubtedly benefited from the proximity of the railway which could carry away the stone much more cheaply than having it carted by road; of course the railway benefited from the revenues from the transport of these stones.

There were never enough passengers nor businesses to make the line profitable and after World War I there were virtually constant threats to its survival. Passenger services were withdrawn from 1st October 1934. From 1934 there was a goods train three days a week from Stirling to Jamestown calling at Croftamie until August 1949, when through working from Balloch to Stirling stopped. From then until October 1959, when Croftamie station closed altogether, a goods train ran three days a week from Balloch to Croftamie. The very last train from Croftamie station was a Branch Line Society special passenger train from Balloch to Croftamie and back on the 17th October 1959 to mark the closure of the line beyond Jamestown station (the section between Balloch and Jamestown operated a goods service until 1964).

What had finished the railway line was the growth of road transport, and by that time Croftamie had carved out a niche for itself in two aspects of that. Stewart Cameron's road haulage company took over part of the old station yard, while close by Buchanan's Car Showroom became one of the largest Volvo dealerships in Scotland. Both have now been closed for many years, being replaced by other businesses such as James D Bilsland and the Scottish Stove Centre. However, the old line still provides a means of road transport – much of it around Croftamie has been converted for use as a cycle track, including the river crossing on the Endrick Viaduct.

As part of local government reorganisation in 1973-4, Croftamie transferred from Dunbartonshire to Stirlingshire believing that Stirlingshire would better manage its rural needs.

KILMARONOCK

Kilmaronock is the Parish immediately to the north and east of Bonhill parish. It starts just beyond Ballaghan at Boturich and ends at Drymen Bridge to the northeast, while to the east it encloses Bonhill by having a common boundary with Dumbarton Parish, south east of the Pappert Hill.

The islands of Inchmurrin, Creinch, Torrinch and the Aber Isle all lie within Kilmaronock Parish. Its name is Gaelic and means “cell of little Ronan”. St Ronan, who died about 737, had a cell or small chapel in the area in the 8th century, and even to-day St Ronan's well is in a wood close to the present day Kilmaronock Church.

At that time the area attracted many Celtic missionaries and St Kessog probably also stayed around Kilmaronock for a time. Almost six centuries later, there is a record of Robert the Bruce giving the church at Kilmaronock to the monks of Cambuskenneth near Stirling, and they kept it until the Reformation in 1560.

A marriage settlement of 1404 involving the marriage of Margaret Dennistoun of Kilmaronock and Sir William Cunninghame refers to lands in the parish whose names are still in use on farms to this day - Cambusmoon, Caldarvan, Duncryne, Easter and Wester Finnery, the Mill and the Mill lands of Mavie - and the lands of Gartocharn. This is the first written reference to Gartchocharn, which was not to become a village until the 1840's onwards.

The Cunninghames were an Ayrshire family who built the Castle at Kilmaronock as it is seen to day - a red sandstone tower, most of which still stands, which was in occupation until about 200 years ago. The Cunninghames eventually became the Earls of Glencairn. One of them built a house in Dumbarton High Street in 1623, which is still standing and is in better condition than most of the rest of Dumbarton Town Centre, although that's hardly very difficult.

The Cunninghames were an Ayrshire family who built the Castle at Kilmaronock as it is seen to day - a red sandstone tower, most of which still stands, which was in occupation until about 200 years ago. The Cunninghames eventually became the Earls of Glencairn. One of them built a house in Dumbarton High Street in 1623, which is still standing and is in better condition than most of the rest of Dumbarton Town Centre, although that's hardly very difficult.

From the Cunninghames, the barony of Kilmaronock passed to the first Earl of Dundonald, (who also acquired Levenside, now Strathleven) at about that time i.e. 1670, and both Kilmaronock and Levenside in turn passed to Lord Stonefield. The Cunninghame family, although they disposed of the barony of Kilmaronock, continued to live and farm in the parish over the centuries.

The present Kilmaronock Church dates from 1813 and acts as the village church for both Croftamie and Gartocharn. The churchyard is still very much the local cemetery. A breakaway church was built in what became the village of Gartocharn about 1770-71, 70 years before the Disruption of the 1840's split the Church of Scotland. This was the Relief Church, and the cause of the breakaway was the same issue thatcaused the disruption - the right of the congregation to appoint their choice of minister. Lord Stonefield, who had become the patron of Kilmaronock a number of years before, wanted to appoint a minister, who was rejected by the majority of the congregation.

The dissenters decamped and built a Relief Church at Gartocharn, which still stands. The churches were not re-united until 1948 but both have continued in use on a seasonal basis, with Kilmaronock being used for summer services and Gartocharn for winter ones.

The dissenters decamped and built a Relief Church at Gartocharn, which still stands. The churches were not re-united until 1948 but both have continued in use on a seasonal basis, with Kilmaronock being used for summer services and Gartocharn for winter ones.

As well as two churches there were also two schools - one called Ardoch Bridge in School Road Gartocharn, the other quite close to Kilmaronock Church on the A811. Although usually referred to as Kilmaronock School, this was the Relief Church School, not the parish school. It closed in 1907, when the school at Croftamie opened, and has been a private house ever since, but it is still quite recognisable as schoolrooms and an attached schoolhouse.

The parish has always been farming in character, although quarries and mills have been operated in it over the centuries. With the modernisation of farming, a number of the farms have been combined, and now many of the farmhouses are owned and occupied by commuters to nearby towns. However, Kilmaronock has successfully kept the urban spread at bay, and is still essentially the rural parish it always has been. Kilmaronock Millennium Hall was built for 2000, as it name implies. It is the parish hall, and lies in the middle of Gartocharn.

Click on above images to view larger versions.

GARTOCHARN

“The place of the humped hill” in Gaelic - garradh being place or enclosure, and carn being humped hill. The humped hill is obviously the Dumpling, or Duncryne to give it its proper name.

The lands of Gartocharn were first documented in 1404, and appear again as Gartcarne in 1485. At that time the reference was to a farm, on the site of which the village grew up centuries later. Gartocharn village is very much a mid 19th century creation.

The New Statistical Account of Scotland published in 1839, says that in the whole of Kilmaronock parish “not even four dwelling houses in it are closely continuous”, and the village does not appear on any map until 1865, although it was established before then.

Until the building of the Dumbarton - Stirling military road, which was started about 1755, the road, or more accurately, track, between Balloch and Drymen ran much closer to the Lochside, down by the Aber shore. The Aber was much more the centre of activity at the time. There was a mill and milldam there, and also a small harbour from which locally quarried sandstone was shipped out via the Loch and Leven to Glasgow. Townhead of Aber and Aber Mill were small but thriving hamlets. The Aber also featured in one of the Duke of Argyll family's few political miscalculations in its rise to the top in Scottish government.

Until the building of the Dumbarton - Stirling military road, which was started about 1755, the road, or more accurately, track, between Balloch and Drymen ran much closer to the Lochside, down by the Aber shore. The Aber was much more the centre of activity at the time. There was a mill and milldam there, and also a small harbour from which locally quarried sandstone was shipped out via the Loch and Leven to Glasgow. Townhead of Aber and Aber Mill were small but thriving hamlets. The Aber also featured in one of the Duke of Argyll family's few political miscalculations in its rise to the top in Scottish government.

In 1685, King James II's attempts to return Great Britain to Roman Catholicism prompted a revolt by the Duke of Monmouth. The ninth Earl of Argyll became its Scottish arm, and marched his troops towards Glasgow from his Inverary base. They crossed the Leven at the ford at Balloch, heading for the Stockiemuir road and Glasgow.

At about what is now the Aber milldam, they heard of government troops ahead. Instead of fighting them there, they took evasive action, aiming to get to Glasgow across the Kilpatrick Hills. This was perfectly feasible, of course, but somewhere beyond Pappert they got hopelessly lost, the army melted into the night. Argyll was captured the next day near Inchinnan, and executed. He would have been on a losing side that time anyway. However, if he had waited another 3 years until the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when James fled abroad– which is what just about everyone else did - he would have survived to a ripe old age.

The Aber lands were sought-after as being more arable and profitable than those further inland, and the farmers who farmed there were referred to as the “Aber Lairds”, by their, perhaps slightly jealous, neighbours. Even before the Relief Church was built in 1770-1, there was a small dissenting Reformed Presbyterian church on the slopes of the Dumpling. Its whereabouts have long been forgotten, but it is known that when a dissenting church was opened at Drymen in 1819, some of the furnishings of the Dumpling Church were gifted to it.

When the breakaway Relief Church was built in 1770 - 1, it was built on the lands of Gartocharn farm, close to the military road. Availability of land, rather than proximity to the military road, was probably the main factor in the choice of the location of the Church. This Church was known at the time, and for many years thereafter, as the Relief Church of Kilmaronock, not Gartocharn.

The military road made an impact, however. For one thing, a stagecoach service started from Balloch Ferry to Drymen using the military road. For another, transportation by carts became feasible for agricultural produce, stones from quarries, timber etc. Therefore, being close to the military road had its attractions. However, the movement to-wards the village was gradual to say the least - it took about 80 years from its completion in the 1760's for the impact to coalesce into a village.

That doesn't mean to say that nothing was happening in the community of what was to become Gartocharn - far from it. Ross Priory had been long established as an outpost of a branch of the Buchanan family, and it was in a bedroom there that one of their regular visitors, Sir Walter Scott, wrote most of his novel, Rob Roy. The view from that bedroom has barely changed in the 200 years since the novel was written, looking out over the Aber and Endrick to the Pass of Balmaha and the hills beyond.

Today's Gartochraggan Farm appears in the novel as “Gartscattachan”. At about the same time, French prisoners of war from the Napoleonic Wars were put to work on the local farms. Tradition has it that it is from these prisoners that France Farm, close to the centre of the village, got its name. This is just about the only new farm name in the area, because if the village is comparatively modern in its development, the farms and their names are decidedly not - most stretching back to at least the 15th century.

Today's Gartochraggan Farm appears in the novel as “Gartscattachan”. At about the same time, French prisoners of war from the Napoleonic Wars were put to work on the local farms. Tradition has it that it is from these prisoners that France Farm, close to the centre of the village, got its name. This is just about the only new farm name in the area, because if the village is comparatively modern in its development, the farms and their names are decidedly not - most stretching back to at least the 15th century.

Family names, too, stretch back over the centuries - the Cunninghames and Buchanans have already been mentioned, but among the most obvious names for most of the twentieth century and before, were the McKenzies, Mitchells, McKechnies, Caldwells and from across the Loch, the Colquhouns. The McKenzies arrived in the area with the purchase of Caldarvan in 1802, and continued to be prominent Glasgow businessmen, even as the expanding family turned to farming. By about 1880 they farmed at Cambusmoon, Mavie Mill, Easter and Wester Finnery as well as living at Caldarvan House.

It was about this time that most of the villas at the heart of the village were built, and the simple lay out of Gartocharn was established. Gartocharn Hotel was a classic Victorian hotel building and also dates from this time. However, we know from an unusual source - a report of a Holy Fair at Gartocharn earlier in the 19th century - that at least two other licenced premises preceded it in the immediate neighbourhood of Gartocharn Church.

Burns wrote a poem about a Holy Fair which was included in the Kilmarnock Edition, and which captures the nature and atmosphere of them perfectly. Holy Fairs were a prominent feature of Scottish rural life in the 18th and 19th centuries. The idea was that a day or so was given over each year at participating churches to a roster of ministers giving pelters to the congregation, in a format virtually indistinguishable from to-day's rock festivals.

There were marquees erected in the church grounds to accommodate the preachers and the congregations, an elevated stage or pulpit, a non-stop stream of preaching activity to keep everyone occupied, if not actually entertained, and food and drink were laid on to sustain the far-travelled crowds. The Relief Church of Kilmaronock ran such Holy Fairs and crowds made their way from the Vale for the fun. A key feature according to a contemporary witness was “the running to and fro during the services from the church to the public-houses, at least two of which were conveniently near”.

Drunkenness, fights and sex were all common features. It is said that it was the minister's wife who pulled the plug on the Holy Fair in Gartocharn, which was the last one in the district. However, Gartocharn has preserved its reputation as a place where people know how to enjoy themselves, as the Poachers Club shows - founded in 1955 and still going from strength to strength. By the late 1950's, the old 19th century Ardoch Bridge School, after which School Road had been named, needed replacement.

The controversy, which surrounded the building of that new school, has long been forgotten. At the time, however, arguments against it ranged from its location, to one councillor saying that Gartocharn didn't need a new school at all. This was at least unique, as it was the only known case of a councillor arguing against a council investing in education in their ward. The school was duly built and opened in 1968, and has proved to be a huge success on its new site. Ironically, shortly thereafter a Gartocharn councillor (perhaps the same one who said a new school was not needed) went one better. He failed to be re-elected (he was an absolute shoe-in) because he forgot to send in his nomination papers on time - he got the date wrong. In the political equivalent of hell freezing over, the seat went to Labour by default. It disappeared in the local government re-organisation of 1974, without being returned to its rightful owner.

Over the years, Gartocharn has been a place where like-minded people slip seamlessly into the community, no matter what their background has been. Perhaps the best example of this is Alistair Pearson. It is hard to believe now that Alistair Pearson only arrived to farm at Tullochan immediately after the Second World War. However, he quickly became a fixture on the local landscape, much mourned at his death in March 1996. Alistair was the most decorated soldier in the British Army in the Second World War, and whilst best known for his exploits as Commanding Officer of 8th Battalion of the Parachute Regiment in Normandy from 00.30hrs of D-Day onwards, he had already fought a hard war in North Africa and Sicily before then.

At Tullochan he settled into being a Gartocharn farmer. Later he became an unparalleled success as Lord Lieutenant of Dunbartonshire, where his leadership, energy and enthusiasm never failed to amaze the wide range of people with whom he came into contact. As comfortable with the man or woman in the street as with the Queen, and with no side to him at all, perhaps the most enduring memory of Alistair is of him sitting in the public bar of Gartocharn Hotel, dog at his feet, surrounded by his farming colleagues, all with dram in hand.

Gartocharn has remained distinctly rural in nature, and has quietly prospered on the back of farming. A number of small businesses, such as Coopers haulage business, grew up to support the farmers' needs, and the local garage and Lomond View Stores do well where other villages have lost such supporting services.

Other businesses and services have contributed to Gartocharn's success and prosperity. Between them, the Hungry Monk (as the Gartocharn Hotel became known before it's latest reincarnation as the House of Darach shopping outlet) and Ross Priory (Strathclyde University's staff and graduate club) employed more than 80 people at peak times.

Other businesses and services have contributed to Gartocharn's success and prosperity. Between them, the Hungry Monk (as the Gartocharn Hotel became known before it's latest reincarnation as the House of Darach shopping outlet) and Ross Priory (Strathclyde University's staff and graduate club) employed more than 80 people at peak times.

The primary school and nursery are booming, attracting pupils from outside their core area and providing about another 20 full and part time jobs. Unemployment is less than 3%, a figure the rest of the country would die for.

The only recent closure of note was the Police Station, which after about 100 years in Gartocharn (the first 50 or so in Duncryne Road) closed it doors in 2001. However, the latest new building, Kilmaronock Millennium Hall is a great success, as well as being a very attractive building with fantastic views over the Loch and the hills. It hosts everything from weddings to a Farmers Market every Friday, in a classic example of how a village or parish hall can be the hub of a vibrant community.

Gartocharn is not immune to change of course. Farms are being consolidated into larger units, and non-farmers already own many farmhouses. New housing development has been quite successfully kept at arms length, and Gartocharn has largely preserved its “green belt” status over the years. Local authority housing at Cambusmoon Terrace was built in the 1930's, and a small local authority development was added in Church Road in the 1950's and 60's, but nothing since then. Some new private houses have appeared here and there, and farming families have been justifiably puzzled sometimes by the difficulties, which they encounter in building new houses on their own land for family members.

The cost of preserving the village as a highly desirable place to live and not allowing any new house building is that house prices go up beyond the reach of young locals, who are priced out of their own village. That is a problem across rural Scotland, of course, not just in Gartocharn.

BALLAGHAN

The name Ballaghan comes from “the place in the hollows” in Gaelic, which is a pretty apt description for the hamlet of Ballaghan. Like much of the surrounding land, the name Ballaghan appears in early charters.

In 1450-1, it is recorded that Isabella, Duchess of Albany and Countess of Lennox, gave the lands of Ballaghan to the Friar Preachers of Glasgow. The Friars seem to have built a chapel in the area, as evidenced by the names of the old adjoining farms of Old Kirk and Shanagles or Shanacles. Shanacles derives from the Gaelic, “sean eiglais” or old kirk in English. Thus we have two adjoining farms with identical names, one in English and one in Gaelic, so it's a safe assumption that there was a small chapel or even very small monastery on that land.

No trace of any such building has been found, although no detailed search, such as an excavation, has taken place. However, the Friars were very much late comers, and much earlier archaeological remains have been found on the site, which provide evidence of some of the earliest residents in the area. In the early 1700's, an urn containing ashes (assumed to be human) was found, which has been dated from about 1,000 years BC.

More recently, a Bronze Age cist (a sort of stone coffin) was uncovered, which dates from even earlier than that, perhaps about 1,200 BC. These finds suggest continuous habitation on this land from the Bronze Age onwards.

The main estate on the Ballaghan lands is that of Westerton, centred on Westerton House. It is mentioned in the Partition of the Lennox of 1493, by its original name of Blarquhosh, when it passed to John Haldane of Gleneagles, after whom the Mill of Haldane is named. By the early 19th century, stone quarrying had joined farming as the major activity in the area. Ballaghan Burn drove a stone mill, which stood where the Reid and Robertson store now is. It cut mainly red sandstone, quarried a few hundred yards to the south of the mill. Some of the sandstone was used locally, but a lot of it was sent to Glasgow. The mill operated for most of the 19th century, and only fell into disuse in the early 20th century, when flooding made the quarry uneconomic to work.

Just east of the mill there was a tenement building, whose nickname of “Paddy's Castle” gives a pretty good idea of the origins of some of its 19th century tenants. Most of the houses at Ballaghan were originally built for the masons and stone millers who worked in the mill - Milton Grove still stands as testament to this. The current houses on Westerton Hill date from the 1970's. One of them started life as the Ballochmyle Hotel, which flourished for a time in the late 1970's and early 1980's, but eventually fell by the wayside. Shortly after closure, the mill was demolished to make way for a bus garage, and it is that garage, plus extensions, which is now the Reid & Robertson store.

The bus garage was always privately owned by whoever was operating the buses on the Balloch - Gartocharn - Drymen - Balmaha route. Owners included McKinlays, until the 1950's, then McFarlane's, and then Barrie's with their Loch Lomond Coaches. More recently it belonged to McColls before they moved to Dalquhurn and then to Strathleven Industrial estate. When Reid & Robertson vacated Dalmonach about two years ago, they took their agricultural supplies business into the former garage building.

DESERTED VILLAGES

There are at least two deserted “villages” on the Lochside, although villages is a bit of an exaggeration, since they both consist of no more than about six houses.

Clachan Dubh is the more southerly of the two, lying on the hillside at about 350 feet, just above the electricity supply lines, close to Stuckgowan estate's southern boundary wall. No one is quite sure why or when it became deserted, but it seems that the estate owner, McMurrich, cleared it for sheep grazing.

Blairstainge is the other deserted village. It lies in Glen Falloch about a mile north of the Head of the Loch, on the east bank of the River Falloch, but high above it, and some distance from it. Walkers on the West Highland Way will be quite familiar with it, since the path passes right through the township. Little is known about Blairstainge - there are no Ordnance Survey or early map references to it. In its day, it wouldn't be considered remote by any means, so it probably was not deserted for improved home comforts. The ruins are similar in build to sheilings, of which there are a fair number in the surrounding hills (sheilings were the rough stone-built huts in which crofters spent the summer when they took their cattle or sheep onto the higher summer grazing). It seems likely that the agricultural changes, which emptied the sheilings, also emptied the village, perhaps about 1850, but that's only a guess.