RENTON A BRIEF HISTORY from 1715 to 2008 - Page 1

Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5

Renton, the most southerly of the Vale villages and towns, has the most distinctive personality of them all. This isn't news to any "Rantonian" or Valeman, nor indeed to many others, from time immemorial.

The late television historian, Dr Ian Grimble, opened one of his shows in the late 1960's / early 1970's standing on Dumbarton Rock looking north. As the camera panned up the Vale to-wards the Loch with the Ben providing, as ever, the perfect backdrop, Grimble said, “This is as far northwest as the Romans got, it marks the north-western boundary of the whole Roman Empire. To paraphrase Julius Caesar, “they came, they saw, they retreated ”, at which the camera shot came to rest on Renton.

If the Vale was the front line in the battle against the Romans, then Renton was the forward observation post. Of course, we're talking about very few people actually living in the area at the time, but there were certainly a number from well before Roman times as evidenced from various local archaeological remains. The best known of these around Renton are the “Standing Stones” at Mount Mallow or Carman Hill. This was probably a hill fort and was only identified by aerial photography in the 1954.

(More info on the Carman Hill Fort here.)

At first, it was dated as belonging to the Bronze Age or Iron Ages (about 1,000 to 300 BC), but it is now thought to date from the Dark Ages - after the Romans left, but before recorded history. It has a wonderfully commanding site overlooking the lower reaches of the Clyde and its sea lochs to the northwest, as well as the whole of the Vale and the Kilpatrick Hills, with quick and easy access to views of the southern end of the Loch. It is also reasonably large, covering an area of more than six acres, so it was probably home to 30-40 people. We will have to wait for future excavations to find out more.

It was about 700 years after the departure of the Romans before we learn much more about the area. We know that William Wallace was a regular visitor to the area during his short life. Indeed Blind Harry, who lived from about 1440 to 1493, and who wrote his epic poetic biography of Wallace about 1477, about 170 years after Wallace's death in 1305, says that Wallace escaped from the pursuing English from the shore at Havoc via a tunnel onto Carman Hill. Blind Harry claimed that he used a written source compiled shortly after Wallace's death, whose author was a boyhood friend of Wallace, and later his personal chaplain.

Most historians think that he relied more on local stories and traditions. Certainly no trace of a Havoc - Carman tunnel has ever been found, but then again, like the Standing Stones, no one has looked very hard. Even if we accept that there is no tunnel, it remains true that Wallace knew the area well enough - too well, he may have felt, since his last few days on Scottish soil were spent nearby, imprisoned in Dumbarton Castle by the traitorous Governor, Sir John Menteith, before being taken to London for execution a few weeks later.

Robert the Bruce, who took on Wallace's mantle, certainly knew the area. After his victory at Bannockburn in 1314 had secured Scotland's independence, Bruce built a castle at what is now Castlehill, in Dumbarton. Between then and his death at Castlehill in 1329, it was Bruce's preferred home.

Robert the Bruce, who took on Wallace's mantle, certainly knew the area. After his victory at Bannockburn in 1314 had secured Scotland's independence, Bruce built a castle at what is now Castlehill, in Dumbarton. Between then and his death at Castlehill in 1329, it was Bruce's preferred home.

He also built a hunting lodge close to what became Mains of Cardross farm, between the Renton - Dumbarton road and the river, and spent much of his time hunting in the Vale and Loch Lomondside, so he would have known the land around Renton particularly well.

As the Middle Ages progressed, various estate and farm names from around Renton began to appear. A tax valuation roll of 1657 lists Dalmoak, Dalquhurn Nether and Upper, and Cordalls, amongst others, and the area had by this time the place names and shape which we can still recognise to-day.

The Romans may be the first recorded failures at conquering Renton, but they certainly weren't the last. Unconquered, idiosyncratic, proud and independent are just some of the words used to describe the people of Renton - sometimes with a range of colourful adjectives thrown in. They are all true and Renton is the better for the many unique differences it shows from the rest of the Vale. To begin with, it enjoys a variety of names - most usually preceded by “the”, which range from variations in pronunciations such “the Rantan” through aspirations to grandeur as in “the capital” to the humbler “the village”.

Sometimes it likes to see itself as “in the Vale, but not of it”, and there is a lot of truth in this. Renton was, and still is for registration purposes, in the Parish of Cardross, unlike the rest of the Vale, which is in the Parish of Bonhill. These days that distinction is totally irrelevant, but it was by no means so for the first  160 years of Renton's existence. The Parish was a local government as well as a religious entity, and matters such as education and poor relief were controlled at a Parish level.

160 years of Renton's existence. The Parish was a local government as well as a religious entity, and matters such as education and poor relief were controlled at a Parish level.

Cardross is only about 2 miles distant as the crow flies, but not many crows seem to have taken that particular route, and the intervening hill makes it a planet away as far as the people of Cardross were, and probably still are, concerned. Renton people quickly learned to fend for themselves as a community and that approach has shown itself in various forms of robust independence of thought and action since Renton's foundation.

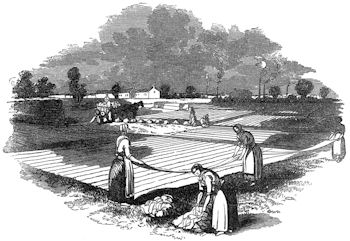

Renton has a very strong claim on a leadership position in the Vale for a number of reasons which shall be touched on. Not least, of course, is the fact that it was at Dalquhurn, on the lands that subsequently became Renton, that the textile finishing industry, which became the foundation of the Vale's prosperity and growth, was first introduced in 1715. This was a very primitive process of bleaching newly woven cloth (linen to begin with, mainly cotton later), by soaking it a number of times in water and leaving it out in the sun between soakings to be bleached in the open air, and thereby the impurities left over from the weaving process were removed.

The prime requirement was a plentiful supply of clean water, which the Leven provided via a lade, and sunshine, which couldn't have been any more plentiful then than it is now. The attraction of the Vale was the purity of the Leven's water, and the attraction of Dalquhurn was that this was where the tide, and therefore the salt water, ended. An additional bonus was that the large bend of Dalquhurn Point made the drawing off of the water into the bleachfields a very easy matter. The only other feature in the process was hedges, which were grown around the bleachfields to stop the cloth being blown away by the wind.

This was, therefore, a very simple, summer time operation, but it worked. An Andrew Johnston started a small bleachfield at Dalquhurn in 1715 and it jogged along on a very modest scale until 1727-28. Walter Stirling, and his partner Archibald Duncan, who greatly expanded the operation, acquired it at that time. They set up the Dalquhurn Bleaching Company on a 12 acre site and increased the number of lades to about 12, the traces of many of which can still be seen. This expansion was financed by £600 from the British Government, which wanted Britain to be independent of continental bleachers, since Britain was so regularly at war with European countries that bleaching cloth in northern Europe could not be guaranteed.

They also imported Dutch bleachers (we weren't at war with the Netherlands) to pass on their considerable expertise. This whole operation was a primitive forerunner of the model deployed over 200 years later when Strathleven Industrial Estate, was set up just across the Leven, funded by the government and with Americans and English playing the role of the Dutch in providing the initial technical know-how. Thus by the 1720's a new industry, and one which was to be the bed-rock of the Vale economy for nearly 250 years, was well established at Dalquhurn Works.

It was not until 1770, eight years after Renton was founded in 1762, that the second of Renton's textile finishing Works was opened at Cordale. William Stirling, who was a nephew of the Walter Stirling who had acquired and expanded Dalquhurn over 40 years earlier in 1727-28, bought the Cordale Estate in 1770 from John Campbell of Stonefield and Levenside (Levenside was renamed Strathleven Estate in the mid 19th century). William Stirling was already a noted Glasgow merchant, with a textile factory on the Kelvin and a booming retail business.

He was rated alongside the great Glasgow Tobacco Lords of his day, but unlike them, he wasn't about to take a beating from the American War of Independence. He is still recognised as one of the leading merchants who helped  Glasgow weather the problems caused by the loss of the tobacco trade as a result of the American War of Independence.

Glasgow weather the problems caused by the loss of the tobacco trade as a result of the American War of Independence.

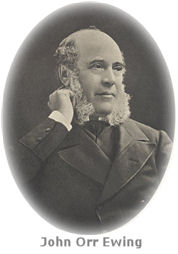

When he acquired Cordale Estate in 1770, William Stirling formed a new company, William Stirling and Sons, and that company operated until it joined with the Ewing and Orr Ewing Works to form the United Turkey Red combine in 1897.

Cordale was founded as a printworks, not a bleachfield like Dalquhurn, and was a very successful operation on its own for over 20 years. Dalquhurn Bleaching Company, too, continued as an independent company, but when in 1791 Cordale Works needed additional capacity, buying Dalquhurn was the obvious solution and that was what William Stirling and Sons did, integrating Dalquhurn into the Company and harmonising their operations. Both Works survived for the next 150 years, both growing steadily from the late 18th century until the early 20th century.

These works were the main source of employment for the people of Renton for the next 150 years. No other major factory was ever opened in the village, but Cordale and Dalquhurn did provide remarkable economic continuity from the 1790's onwards. William Stirling and Sons developed Cordale as two distinct entities - Cordale Printworks was built on the Point beside the river. West of it, a quite separate estate was walled off on the land between the Point and the Military road and Cordale Estate laid out and Cordale House built, of which more below.

Dalquhurn bleachfields were laid out on land acquired from William Cochrane of Kilmaronock, and their immediate neighbour was James Smollett. The Smolletts were a leading Dumbarton family in the 17th century, who were merchants and lawyers. James aspired to join the landed gentry and bought Place of Bonhill just a few yards across the Cardross - Bonhill Parish boundary of Poachy or Mill Burn, in 1684. This gave him the entitlement to call himself “Smollett of Bonhill” which the family retains to this day.

In 1692, he added Dalquhurn Estate to his properties in the Vale, so by then he owned a good deal of the land on which Renton was later built. Dalquhurn Estate, which was small by Smollett's standards, included Dalquhurn House, which adjoined the bleachfield. Sir James, as he became, having been knighted in 1690 by King William III, lived at Place of Bonhill, but one of his sons and his children lived at Dalquhurn House. It was at this House in 1721 that Tobias Smollett, James's grandson, was born.

Tobias Smollett became one of the earliest novelists in the English language, and was one of the best-known and best-regarded writers of his day. Among his novels were Roderick Random and Humphrey Clinker, while his best-known poem, “Ode to Leven Water” definitely dates from before the arrival of the large-scale textile industry on the Leven's banks, with its lines

Tobias Smollett became one of the earliest novelists in the English language, and was one of the best-known and best-regarded writers of his day. Among his novels were Roderick Random and Humphrey Clinker, while his best-known poem, “Ode to Leven Water” definitely dates from before the arrival of the large-scale textile industry on the Leven's banks, with its lines

“Pure stream, in whose transparent wave

My youthful limbs I wont to lave”

Although the two novels mentioned above are still in print, most Vale folk can go through 11 or more years of schooling without reading a word of them, while Ode to Leven Water only ever seems to get an outing as part of the toast to "Oor Toon" at Alexandria Burns Club's annual Saint Andrew's Night celebration. This neglect of local and national culture is absurd, of course, not least because Smollett was a man of moral as well as physical courage, and examples such as he are in short supply in every age.

His moral courage is exemplified in his poem “The Tears of Scotland”. It was written as a condemnation of Cumberland's treatment of the Highlanders after Culloden in 1746, and its appearance at all, rather than its quality, is what marks it out as deserving attention.

Tobias Smollett never lived any of his adult life locally, spending most of it in London and in the Royal Navy, as a naval surgeon. To have written such a poem in the climate of the times was a considerable risk, to do so and serve in the Royal Navy was courting severe punishment. Smollett confronted the risk and survived. He died in Livorno (Leghorn) in Italy in 1771.

His reputation in the United States, particularly in academic circles, has always been far higher than in the UK, but even here it is undergoing something of a revival, with the publication of a recent biography. Had he lived just a few years longer, he would have inherited the lands and title of “Smollett of Bonhill” from his cousin James, who died at Cameron House without descendants in November 1775. He would therefore have lived in some style and comfort, instead of the poverty in which he died.

Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5