BONHILL PAGE 2

PAGE 1 | PAGE 3 | PAGE 4 | PAGE 5

The Vale escaped the wars of the mid 1600's - the Bishops War, the Wars of the Covenant and the overspill from the English Civil War, which saw Cromwell's  incursion into Scotland.

Although his forces were present at either end of the Vale and must have passed through it - they took control of Dumbarton Castle in 1652 and they burned the McFarlanes out of their castle on Inveruglas

isle in 1654 - they left the Vale untouched. Nor was it much affected by the religious troubles in which these wars were based. Charles I wanted to Anglicise the Church of Scotland by changing

church ritual and introducing bishops.

incursion into Scotland.

Although his forces were present at either end of the Vale and must have passed through it - they took control of Dumbarton Castle in 1652 and they burned the McFarlanes out of their castle on Inveruglas

isle in 1654 - they left the Vale untouched. Nor was it much affected by the religious troubles in which these wars were based. Charles I wanted to Anglicise the Church of Scotland by changing

church ritual and introducing bishops.

This provoked an angry response in Scotland that led to the signing of the National Covenant in 1638, and the formation of the Covenanting movement, which was eventually to play a large part in the shaping of the organisation of the Church of Scotland - an outcome which seemed unlikely for nigh on 50 years.

It was the Restoration of Charles II to the throne that

revived the dormant Covenanting movement. Like his father,  Charles wanted to bring the Church of Scotland back under his control and he re-introduced bishops. There was opposition, but he did have the

upper hand and he did not want to overplay it. Charles, as he said many times, had no wish to “go on his travels again” and he was happy to reach limited accommodations where he could, although

a large number of ministers who would not accept bishops were sacked.

Charles wanted to bring the Church of Scotland back under his control and he re-introduced bishops. There was opposition, but he did have the

upper hand and he did not want to overplay it. Charles, as he said many times, had no wish to “go on his travels again” and he was happy to reach limited accommodations where he could, although

a large number of ministers who would not accept bishops were sacked.

Many Presbyterians, particularly in the Southwest, revived the Covenant and were hunted down for practicing their religion. To defend their meetings or conventicles, many of which were held outdoors, they formed an armed guard, which was styled the Cameronians, which was later incorporated into the British Army as the Cameronians Regiment. This period of the late 1670's - 1680's became known as “The Killing Times” because of the violent intensity of the government's action against the Covenanters.

Covenanting was not strong in the parish of Bonhill - in fact the opposite was true, since the minister of the time, William McKechnie, was a supporter of his boss the bishop, unlike his colleagues at Luss and later Kilmaronock who were sacked from their churches. Most of the locals just kept their heads down - there were not many of them anyway. It is reckoned that there were only about 350 people in the whole parish in 1643. However, there was one brave Bonhill soul who stood up for religious freedom against the aggressive intimidation of the government forces.

This was a Bonhill man called Robert Nairn. Nairn was a shoemaker and a  Covenanter, and he refused to attend Bonhill Parish church, which was now part of a church headed by bishops, with McKechnie as

minister. It had become a criminal offence not to attend Church, and he had to leave home and hide out with friends, or in the open, from the officers of the law from Dumbarton who were very actively

hunting for him.

Covenanter, and he refused to attend Bonhill Parish church, which was now part of a church headed by bishops, with McKechnie as

minister. It had become a criminal offence not to attend Church, and he had to leave home and hide out with friends, or in the open, from the officers of the law from Dumbarton who were very actively

hunting for him.

Amongst the places he hid out for a time was Napierston Wood. However, the cumulative effects of what we would now call living rough, caught up with him, and, very ill, he returned home to die on 15th April1685.

Even in death, the Church still hounded Nairn and McKechnie refused him burial in Bonhill Churchyard. However, by this time the locals had had enough of the Church's attitude, and some young local lads broke the locks on the Churchyard gates and guarded his burial service in Bonhill Churchyard. A descendant, Thomas Nairn of Bankhead in Balloch, erected a gravestone on his grave in 1826.

Local tradition had it that he had been sheltered for a time in the farm of the McAllisters of Mid-Auchencarroch (who held on to their strict Covenanting views until the 1850's and beyond) and sure enough, when in the early 1800's a barn was demolished during renovations of their farm, a secret room was uncovered behind a double gable in which they found Nairn's lapstone, just where he had left it 120 years before. Other of Nairn's artefacts seem to have been passed down within the family and other of his descendants, the Nairn Marshall's who became wealthy in the 19th century and built and lived at Dalvait House in Dalvait Road Balloch until about the Second World War, loaned some of them to be displayed at the Empire Exhibition at Bellahouston Park, Glasgow in 1938. They seem to have been lost from sight since then.

For most of the 18th century Bonhill was indeed a “wayside village” where nothing much happened outside of the usual farming activity. One bright spot would have been the occasional drive of cattle, more in the autumn, from Argyllshire en route to the Glasgow market, which would have crossed the Bonhill Ford. This ford had been in operation since time immemorial, and was only closed when the first Bonhill Bridge was built in 1836. The area on the east bank of the Leven, just about where the toilets used to be, where the cattle shook themselves dry after crossing the ford, was for many years known as the “dripping ground”. At some time, probably in the late 18th century when the bleach fields and dyeworks had already started, the ford crossing was supplemented with a ferry service, owned by the ground superior, Smollett of Bonhill.

The ford could not be used when the River was high and boats were common on the river for centuries before the bridge, so it is likely that there was some ad hoc arrangement for crossing the river by boat before a ferry service was introduced. Since there were not many inhabitants and since most of them had little reason to travel, there wouldn't have been much demand for a ferry crossing at Bonhill anyway until the late 18th century, although the exact date when the ferry started is not known.

The crossing was just to the north of where the Bonhill Bridge is now, and the ferryman's house stood more or less where the dental surgery is now at the north east corner of Bridge Square on the west bank of the Leven. Smollett, who probably still lived close by at Place of Bonhill House when the ferry service started, owned the ferry crossing at Bonhill. It was a nice little earner for him, and the revenues he took from it were the basis of a running sore in the life of the whole Vale for much of the 19th century.

One activity that probably did generate cross-river journeys before the coming of industry was going to Bonhill Parish Church on a Sunday. The old, small, medieval church was replaced in 1747 with a larger building to accommodate a parish population which had by then grown to about 900. A manse was added in 1758 in front of the Church in what is now the Churchyard. This Church only lasted until 1797 when a larger Church was built, reflecting the substantially increased village and parish population - the parish population had increased to 2,700 by 1800. The quality of the build did not seem to be a strong point with Bonhill Church at that time. This Church was built nearer the river on poor foundations and soon the walls started to split. The manse seems to have been little better. The minister who arrived in 1809 and stayed on until his death in 1848, the Reverend William McGregor, was a man of strong character and stronger opinion. Although he was a confirmed bachelor, and it might be thought that his domestic standards were at best flexible, he took one look at the state of the manse and decamped to a house at Mill of Balloch in Dalvait Road Jamestown where he based himself for the 39 years of his tenure.

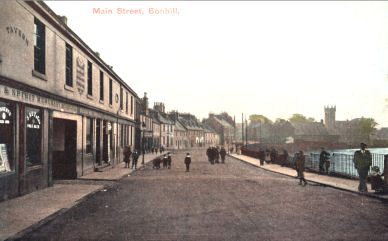

Bonhill Main Street (Click to Enlarge)

In about 1755, as part of the continuing military road-building program, the road from Dumbarton to Stirling was upgraded from a track to a military road. It came through Bonhill on the line of the “back road” which existed until the building of the hillside housing estates from the 1960's onwards. There was a local tradition that during its construction, General Wade's soldiers used and upgraded Ladyton Springs. The soldier part of that tradition could well be true, the General Wade part certainly is not. He was not involved in any road building projects in Scotland after 1737, and left Scotland for good in 1740. The road through Bonhill would have been built under the supervision of Wade's successor, Major Caulfield, who was responsible for the building of by far the largest part of the military road network.

The military road became part of Main Street Bonhill, and its construction was very timely indeed, because the textile trade had already taken hold in the Leven Valley and was shortly to make its first appearance in Bonhill. It is worth noting, though, that the Dumbarton - Bonhill - Balloch road had a poor reputation with passengers, especially coach travellers. Even in the 1820's, when steamers started to sail from Balloch onto Loch Lomond, and passengers were coached into Balloch from Dumbarton they complained bitterly if they were transported via Bonhill. Not only was the road surface rough, the route was a bit up hill and down dale. The two circumstances made for a sore and uncomfortable ride, and unhappy passengers by the time Balloch was reached. The flatter road on the west side of the Valley was much preferred.

There were already five bleachfields / printworks in the Vale, before the first one was opened in Bonhill. It is a fair assumption that some of the workers in what were still very small factories had already settled in Bonhill before Dalmonach Works, Bonhill's first large factory, opened in 1786. The village had probably started to expand before 1786, and it continued to do so for another 100 years.

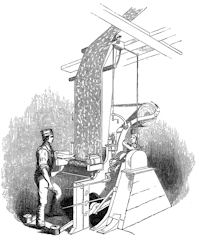

Dalmonach Works (Click to Enlarge)

From the outset Dalmonach was a printworks, as opposed to a bleachfield, and although it started on a very modest scale it went on to much greater things. To begin with it had a succession of partners,

including the Kibble family of Garelochside, who are now best remembered for the Kibble Palace, newly restored and re-opened in the Botanic Gardens, Glasgow, which they donated to the city. Dalmonach

Works was destroyed by fire in 1812, and was rebuilt to a design and under the supervision of Henry Bell of the steamship “Comet” fame. Dalmonach was an innovative works in terms of technology

and education, and was highly regarded by its peers in the Vale. It was for many years regarded by  most people in the industry as the most important works in the Vale. There are many examples of its

leadership in technology - it was the first works to use a two-colour printer, which it did about 1814.

most people in the industry as the most important works in the Vale. There are many examples of its

leadership in technology - it was the first works to use a two-colour printer, which it did about 1814.

< Click Image to Enlarge

Later Dalmonach had machines capable of printing on cloth 60 inches wide, and printing 16 different colours. These machines were the only ones in Scotland capable of printing so many colours. At its peak it had 28 machines at work, and the works employed more than 800 people. It passed through a number of owners and name changes in mid century but by 1871, it reverted to James Black & Co., the name it retained until it closed in 1929.

Dalmonach's destiny was sealed in a few months between 1898 and 1899. In July 1898, James Black & Co was floated on the stock market as a public company. The floatation left the company exposed to being taken over, and this is exactly what happened. In 1899, the Calico Printers Association, (CPA), was formed in Manchester by 46 British textile companies, 32 English, 14 Scottish. The aim was to use size to protect everyone's commercial interests. The theory was that the benefits from economies of scale and wider market contacts, which on paper the CPA represented, would considerably increase the founding companies' future success. The reality was quite different, which was what some people in the Vale had warned when James Black joined the CPA. Because CPA's English firms dominated it, the CPA gave work to them first, regardless of how efficient or suitable they were. Within three years the CPA had lost half of its floatation value of £6 million. The words of an irate shareholder at the third AGM of the CPA cannot be improved upon to describe the situation: “ the shareholders have received nothing for the last two years, and the shares have depreciated to the extent of £3,000,000. The position of the Association represents a disaster unparalleled in the commercial annals of Manchester”. The impact at Dalmonach was dramatic. Between 1906 and 1909, Dalmonach was running at much less than full capacity while by 1910, the workforce had been substantially reduced. By this time CPA had already closed a number of other, hitherto successful, operations in the West of Scotland. The works were now in steady decline and finally closed in 1929, another victim of remote management. Thirty years later in 1960 the CPA came back to the Vale to finish off the UTR.

When James Black & Co became owners in 1831, Dalmonach's reputation for innovation was extended to education and social issues. In the early 1830's, James Black built Dalmonach School on the site of a blacksmith's shop at the main gate of the Works, where it still stands to-day. Dalmonach School was not just a typical works school, offering part time education to children who worked for James Black. It aimed to attain the highest education standards for all pupils, and it id that by attracting the best teachers. Fees were kept very low and its pupils came from all over the Vale, from Dumbarton and from the Lochside. It retained its reputation until about 1870 when the Parish School Board was taking its responsibilities seriously enough for Black to transfer the pupils to the state education system and close down Dalmonach School.

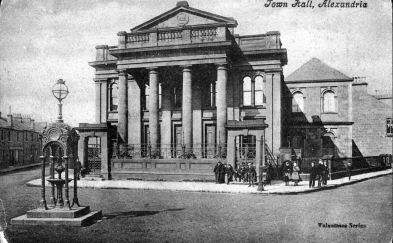

Alexandria Public Hall (Click to Enlarge)

However, the School had always been made available to many organisations as a meeting place. The Vale of Leven Mechanics Institute and Library, a club for Vale folk at which scientific, industrial and engineering matters were considered, met there for many years before transferring across the river in 1863 to what was then the new Public Hall. The first Sunday School in the Vale met there, as did various new church congregations awaiting the building of their churches.

PAGE 1 | PAGE 3 | PAGE 4 | PAGE 5