World War One and the Vale of Leven

Introduction Page 1

4th August 2014 is the centenary of the First World War – the event which defined the World for the next 100 years. After the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on 28th June 1914, the various European alliances clicked into gear and Europe stumbled into War. Britain was bound by treaty to defend Belgium from attack, as indeed was Germany itself, and it issued an ultimatum to Germany to respect Belgian neutrality. However, Germany’s plan of attack on France, the amended Schlieffen Plan, involved attacking France through Belgium and Germany duly invaded Belgium on 4th August 1914.

That was the German answer to the British ultimatum and at 11 pm London time (midnight in Berlin) on the evening of Tuesday the 4th August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. As the British Foreign Secretary of the day, Edward Grey, said “the lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time.” Although one hundred years on that comments might seem a bit too sentimental for current tastes, it proved to be one of the more accurate forecasts of August 1914.

Every combatant country was changed for ever by the War and although the changes were more profound in some countries than in others, it was the first war in which the impact was felt profoundly in every community in every combatant country. This was of course because of the vast numbers of soldiers involved in the fighting.

Every combatant country was changed for ever by the War and although the changes were more profound in some countries than in others, it was the first war in which the impact was felt profoundly in every community in every combatant country. This was of course because of the vast numbers of soldiers involved in the fighting.

Britain in particular had never had an Army anywhere near the size it required to conduct its part of the war from 1915 onwards. Unlike the major continental countries the British Army was totally voluntary – the Regular Army, the Reservists and the Territorial Forces were all volunteers. So on the declaration of war, there was no immediate empting of towns and villages of all of their young men. For the few days immediately before and after the outbreak of war, neighbours might have noticed small numbers of Reservists going off to rejoin units in which they might have last served as long ago as 10 years previously, Reservists being men who had previously served in the Regular Army. Most of them had long settled into civilian life, had got married, had families to raise and were in reasonably well paid jobs. You can imagine that most of them were not best pleased at having their civilian lives disrupted, and neither were their wives. But off they had to go, usually by train from Alexandria or Renton stations, seen off by their wives and children, to join their units wherever they were, preparing to depart for France.

All of the British casualties until the spring of 1915 were either Regulars or Reservists and a substantial proportion of them had wives and families. Later casualties tended to be sons or nephews rather than husbands and fathers, although there were still plenty of them too.

The other group of volunteers who were mobilised were the members of the local Territorial Force companies. The Vale and Renton had a strong Territorial Army tradition organised into two companies of the 9th Battalion of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders (The Dumbartonshire Regiment). These were E Company – Bonhill & Jamestown Company which had drill halls in both villages and F Company - Alexandria and Renton Company which also had drill halls in both towns.

On the evening of 4th August 1914 the local Territorials were ordered to report to their battalion depot, which in this area was at Dumbarton. There they were billeted in the local schools, which was an official secret for a week, before mustering on the Common on Tuesday morning 11th August 1914 and entraining at what was then known as the Joint Station and is now Dumbarton Central, to head south to their training camp at Bedford, where they stayed until crossing to France in the spring of 1915.

This quiet, almost unobtrusive, approach to going off to fight didn’t last more than a few days, only until Lord Kitchener’s appeal for volunteers which was issued on 8th August 1914. On the outbreak of war Lord Kitchener was appointed the Secretary of War to serve in the Cabinet of Herbert Asquith’s Liberal Government. Although Asquith proved to be a mediocre war-time Prime Minister, until the outbreak of war he had been a very successful peace-time Prime Minister and his Cabinet included some of the most competent British politicians of all time such as Lloyd George, Winston Churchill and Edward Grey. Kitchener was more than capable of holding his own in that company. On military matters he dominated it for the next 18 months or so.

This quiet, almost unobtrusive, approach to going off to fight didn’t last more than a few days, only until Lord Kitchener’s appeal for volunteers which was issued on 8th August 1914. On the outbreak of war Lord Kitchener was appointed the Secretary of War to serve in the Cabinet of Herbert Asquith’s Liberal Government. Although Asquith proved to be a mediocre war-time Prime Minister, until the outbreak of war he had been a very successful peace-time Prime Minister and his Cabinet included some of the most competent British politicians of all time such as Lloyd George, Winston Churchill and Edward Grey. Kitchener was more than capable of holding his own in that company. On military matters he dominated it for the next 18 months or so.

Kitchener was a very intelligent man who had had a successful career fighting the sort of wars in which the British Army had, after much failure, managed to become quite competent – against lightly armed and unorganised inhabitants of lands which Britain had decided to colonise. The reverses which Britain had endured in the Boer and South African wars had forced major reorganisations in the Army, and therefore the British Army of 1914 was as fine a fighting force as any in Europe, but far too small for the job in hand in 1914. Kitchener had played a part in creating this modern army and his successful campaigns with it had earned him the respect and affection of the British public.

Even as the losses mounted he managed to maintain that popularity with the public, if not with his colleagues, both civilian and military, until his death by drowning when the ship on which he was sailing to Russia struck a mine off Orkney and sank in June 1916.

Unlike some around him, Kitchener knew that it would be a long war and that the British Army of 1914 was far too small to fight it. If he had had his way, Britain would have maintained its century-old policy of not engaging in continental wars but instead use the British Navy to enforce a blockade in favour of its continental allies (the Royal Navy did maintain a blockade on Germany and by 1918 it was so successful that the German home front collapsed, substantially weakening the German Army’s efforts at the front.) However, Kitchener knew that this was not an option and set about creating a number of New Armies each of 100,000 men, recruited and trained from scratch.

In taking this approach he by-passed the Territorial Forces for which he had an unjustified low regard and which were to perform as well as the regulars when given their chance on the western front in 1915. Inevitably his armies were going to require millions of men and although he was slow to appreciate the huge amount of munitions and ancillary material his armies would require to support their fighting he certainly understood that the whole country would be involved and society would be radically changed by the war effort.

And so of course it turned out. Virtually every family in the country had a family member involved. In virtually every street someone was killed during the war and many more wounded or captured. On this website we have already told of the building of the war memorials after the war and listed the names of the men who were killed in the fighting.

Although the war impacted on every aspect of society (and there are many stories to be told about industry, social issues and civilian life during the war), our first duty is to tell of the men – and women - who served and suffered.

Vale men served and died in the Army, Royal Navy and the Royal Flying Corps, later the Royal Air Force. They served in virtually every theatre of the war from Flanders and France, Italy, Serbia and Salonika, The Dardanelles / Gallipoli, Egypt & Palestine, Africa, Mesopotamia and even in Afghanistan; they served at sea including at the Battle of Jutland, the one major naval battle of the war. They are buried in graveyards or their names are commemorated on war memorials in most of these theatres, as well as the Royal Navy Memorials at Chatham and Portsmouth.

Menin Gate Memorial Ypres , Names on Interior Walls and Arches

A number of women from the valley also went off to serve, usually as nurses, wherever the fighting was heaviest such as France and Flanders but also in Serbia and Egypt. Although thankfully, none from this Valley were killed, many nurses from elsewhere did die since they often worked in dressing stations close to the front, certainly closer than the top brass based themselves.

Unfortunately there is no accurate figure of how many men left this area – Bonhill, Kilmaronock, Luss parishes and Renton – to go and fight; the best estimate that we can arrive at is just over 3,000 and we’ll explain how we arrived at that figure and some others below in this Introduction.

We know the names of 559 men on the 4 local war memorials and we have managed to prepare short biographies of over 450 of them so far. In addition, we have found a number of local men who were killed but whose names, for whatever reason, do not appear on any local memorial. Also we have so far been able to identify another 300 or so men, who were wounded or captured, but we shall add substantially to this list as our researches go on. These short biographies and names will start to appear in a few weeks and will be regularly added to as more details and additional names are found. Assuming that the ratio of men killed to men wounded applies to Valemen as it does to the rest of Scottish servicemen (1:2.3) then is fair to assume that about 1,300 Valemen would have been wounded / captured / fallen ill with a whole variety of trench-based diseases such as dysentery and typhoid.

The story of these men and women will be told in the section called “The Men Who Marched Away”. This is a major undertaking and will be a work in progress for some time with regular updates as and when it is appropriate The aim is to provide:

1. A “Roll of Honour” covering the 3 parishes and Renton - a list of as many of the men who served as possible. Hopefully this will include a full name, the town / village from which they came and hopefully their address, the regiment in which they served and any other information we can find out about them. Being realistic it’s not foreseeable that we’ll be able to collect anything like a complete list but we’ll do our best.

By its nature the most readily available names come from people who were killed and wounded / sick / captured and since we aim to provide short biographies of those killed and details of those reported wounded, there will be a certain amount of duplication, but that’s better than omission. Accompanying this Introduction we’re also publishing an article on Rolls of Honour which were and were not prepared in the Valley. Pride of place on this subject goes to the 1915 Renton Roll of Honour, which vindicates all of the stories down the years about Renton’s contribution to the war effort in WW1.

2. Short Biographies of Valemen who were Killed during the war. Men actually died for a whole variety of reasons from “Killed in Action”, to typhoid and dysentery in the trenches, and men accidentally killed. Even men in uniform who were on leave are included as died on active service.

- The first man from the Vale whose death in action was reported in the Lennox Herald on 7th November 1914 (it had already been reported on 5th in the Glasgow Herald) was Lance-Corporal Thomas Murphy, 2 KOSB of 13 North Street Alexandria who was Killed in Action on 22nd October 1914 during the Battle of La Bassee. Having no known grave his name appears on the Le Touret Memorial in Northern France. However it does not appear on the Cenotaph in the Christie Park and we can only assume that all of his Alexandria connections had either died or left the area by the time the lists of the dead were being drawn up after the war.

However, he was not actually the first man from the Valley to die in WW1. That dubious “honour”, which I’m sure he’d happily have foregone had he known anything about it, fell to Private James McFadyen of 37 Back Street Renton whose short biography appears below. He was killed on either the 20th or 21st October 1914, although it took the War Department a long time to confirm his death as you will see. James McFadyen’s short biography is as follows:

Private James McFadyen, (3/3933) C Company, 2 ASH, 37 Back Street Renton. James McFadyen was probably the first person from the Valley to be killed in action, on either 20th October 1914 (information received by his mother from one of his fellow Argylls who was home wounded) or the 21st October 1914 according to the Scottish National War Memorial; there is no Commonwealth War Graves Commission record for Private McFadyen. His mother was told at first by the War Office that her son was missing. He had been a regular correspondent with her before the 20th October and she had received no letters from him since before that date, so it was obvious to her that the silence was ominous.

His comrade who was home wounded told Mrs McFadyen that it was virtually certain that her son had been killed in the fighting in the 1st Battle of Ypres. He told her that McFadyen’s section had been outnumbered on the day in question and was almost completely wiped out. Although he had been born in Dumbarton he belonged to Renton, where he “resided in the famous Back Street there, a street which has given many fighting men to their country during this present crisis” (the Glasgow Herald). He was a Reservist having been a Regular many years before, serving in the South Africa War. He was now about 34 years of age and was employed at McMillan’s Yard Dumbarton when called up at the outbreak of war (another report said that he was a labourer in Denny’s Yard).

3. A List of Valemen Wounded / Sick / Captured. There were weekly reports of the wounded in the Dumbarton and Lennox Herald and from time to time in the Glasgow Herald, and it is from these reports that we are building up this List. It is a time consuming piece of work and we will add to it as the research continues. This entry on the list is a good example of how Jimmy Russell followed up on people recovering from serious wounds:

- Private Festus Harkins, (9497) C Company 2 ASH, 139 Back Street Renton. It was reported in the Glasgow Herald of 25th December 1914 that Mrs Harkins, Back St Renton, yesterday received a telegram from the War Office stating that her husband Private Festus Harkins C Company A&SH was dangerously ill from a gunshot wound on the face. He received this wound at the front on December 13th 1914. He lies in the General Hospital Boulogne. He took part in the Boer War and is one of 3 brothers with the colours. A Reservist, he was employed as a holder-on at McMillan’s Yard Dumbarton when called up.

Reports in January 1915 say that he had been dangerously wounded and has been moved to 4th General Northern Hospital Southampton. He has received 6 wounds, chiefly in the head. His wife has received word that he is as well as can be expected. At first his condition was very serious but it is now expected that he will pull through. By March 1915 it was reported that he was lying in Lincoln Military Hospital. Festus Harkins did survive these wounds.

Existing Stories from Soldiers Who Served

Of course, we already have a number of interesting stories on the web-site about men who served and we shall be adding to them as more material is received. Two excellent War Diaries of local men which continue this story-telling are now appearing on the web-site for the first time with this update.

With this first edition of The Men Who Marched Away we are very fortunate to be able to publish two contrasting and fascinating war diaries of local men – one the diary of Private John Hogg of Alexandria, who was sent off to the Khyber Pass in 1917 where he took part in the Third Afghan War. This is in downloadable PDF format.

The other is the diary of Sir Iain Colquhoun, the laird of Luss who fought bravely on the Western Front, was wounded and decorated, but was nonetheless court-martialed for being judged to have observed a Christmas Truce in December 1915. It was Billy Scobie who made available to us a copy of Sir Ian Colquhoun’s Diary, which has been in the Imperial War Memorial, London, for a great many years.

Coming in the Near Future.

There are of course many other Vale stories from the Great War which will duly appear. These include:

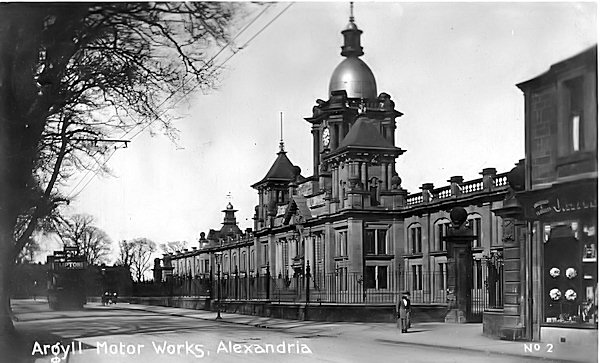

1. The Belgian Refugees who arrived in Alexandria December 1914 and departed almost exactly 4 years later in December 1918. They were driven out by the German invaders who destroyed their homes in the towns and villages of Flanders. They mostly worked in the ex-Argyll Motor Works and lived in Govan Drive, Argyll Street and later “The Huts”. They are the one group of immigrants to the Vale who have left absolutely no trace but we do have the names and trades of many of them and we’ll list them in the remote hope that maybe someone in Belgium will one day see the list and get in touch.

Destruction in Ypres Walter Bisland Collection

2. The Former Argyll Motor Works During WW1. Although it’s commonly believed that the Argyll Motor Works closed down completely in June 1914, there were still actually 400 people working there the day war broke out. Ironically, in common with all the other local factories, management’s first reaction was to cut back their employees working hours. The government initially had a small number of munitions suppliers to whom they awarded all munitions contracts and one such was Armstrong Whitworth who were head-quartered at Elswick, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Armstrong Whitworth knew that it had to increase its capacity as a matter of urgency and it bought the premises, shop floor machinery and some of the stock of the Argyll Motor Works in December 1914. From shortly thereafter it produced shells for the Admiralty and the Admiralty eventually took over direct control of the Factory, although Armstrong Whitworth continued to operate it on a day-to-day basis. The Admiralty renamed the works the Royal Naval Ammunition Factory, Alexandria (“RNAF”) a name which it retained until its closure on 31st December 1919.

Argyll Motor Works becomes Royal Naval Ammunitions Factory

However the Vale people called it “The Gunworks”, although it never at any time made a single gun, and that’s a name which we’ll also use from time to time in the articles about the Factory. The Factory was the Vale’s main civilian contribution to the war effort but from 1915 onwards a number of different issues arose and we will tell the stories around them. The stories are a good barometer of the mood of the people of the Vale; inevitably the public mood became more sombre, perhaps even bitter, as the war went on, and this certainly is reflected in the public reaction to these different issues. These issues included:

- The number of young single men who were working in the Gunworks. These young men received exemption from military service under the government schemes for exemptions for people who worked in an industry which was vital to the war effort such as munitions. The young men still working in the Royal Naval Munitions Factory were accused of being “cowards” and “shirkers” by many members of the public and a campaign was led by the Bonhill Parish Council to winkle them out and force them into the armed forces.

- They were replaced by young women but that didn’t satisfy many Vale men because having proved that they could do the job as well as the men they were replacing, under government regulation the women achieved equality of pay. This gave some poor souls apoplexy and the Lennox Herald’s Letters to the Editor make comical reading to the present day reader. There was clearly no pleasing some people and the Vale’s well-tuned misogyny returned once more to the fore

- The incompetence and deceit verging on fraud in the management of the factory, of which there were many accusations at the time, and which were mostly confirmed by a court case in the 1920’s.

- The part played by Bonhill Parish Council in bringing concerns about these issues to the government’s attention at the highest level.

The Role of the Press, National and Local, In Covering the War. From the outset the War Office exercised very tight control over reporting from what it called “the war front”. As a result you cannot believe a word in the war reports in the national press for the first couple of months.

The casualty reports are especially noticeable not only for the delay in their appearance – the first one did not appear until 3rd September 1914 and that list contained only Officers names, while it was 9th September 1914 before any casualty list containing the names of Other Ranks was issued. By that time the first major battles at Mons (22-23rd August) and Le Cateau (26th August) had taken place and the Battles of the Aisne and Marne were still going on; thousands of men had been killed, wounded and captured. The striking class distinction in Casualty Reports was maintained throughout the war.

The casualty reports are especially noticeable not only for the delay in their appearance – the first one did not appear until 3rd September 1914 and that list contained only Officers names, while it was 9th September 1914 before any casualty list containing the names of Other Ranks was issued. By that time the first major battles at Mons (22-23rd August) and Le Cateau (26th August) had taken place and the Battles of the Aisne and Marne were still going on; thousands of men had been killed, wounded and captured. The striking class distinction in Casualty Reports was maintained throughout the war.

In stark contrast, the Lennox and Dumbarton Heralds are mines of information about local men in the forces and especially of the dreadful conditions at the front – not a word of which was appearing in the national press. The two Heralds placed almost no restrictions on information which came into their hands about local soldiers in the trenches. This information usually came from letters to a soldier’s family and passed on to the paper’s reporter; occasionally it came from an interview with a wounded soldier on home leave.

The papers faithfully reported what the soldier said, no matter how bad a picture it painted of how awful conditions were or how the fighting was taking such a heavy toll of British soldiers.

In many ways it was these papers’ finest hour. The Vale was particularly well served at this time in that James Russell was the papers’ Vale correspondent and he faithfully went round the streets of each village and town and collected whatever information he could about the servicemen.

In many ways it was these papers’ finest hour. The Vale was particularly well served at this time in that James Russell was the papers’ Vale correspondent and he faithfully went round the streets of each village and town and collected whatever information he could about the servicemen.

As he was to do in later years on so many different subjects in the Vale, Jimmy Russell was the reporter of record: accurate to a fault, even-handed, thorough and with an unfailing nose for the public mood. He was an invaluable source of information about the Vale during the war (and after) without whom these pages would be very much poorer.

The Government promises to the Servicemen. To encourage men to enlist specific undertakings were given to soldiers that they didn’t have to worry about what might happen to their families. The government would look after them. Variants on such promises were repeated during the war, accompanied by such slogans as “a land fit for heroes”, “homes fit for heroes”. None of the promises were kept, of course, and even in an age when the public is hardened to politicians’ mendacity and downright deceit, when the term “military contract” can be seen in all its insincerity, the blatant disregard of promises made to the WW1 soldiers still shocks.

Soldiers encountered this deceit when still serving, but the severe economic problems after the War, which were particularly bad in the Vale in the 1920s, exposed the deceit in all its callous disregard for the promises made when there was a war to be one.

The War on the Home Front. During war-time many aspects of life continued in the Vale with an apparent air of normality. Annual Flower Shows continued to be held, Bowling and Golf Clubs held their usual annual competitions and posted the results in the Lennox, people still sat for musical qualifications. Day trippers still came to Balloch to sail on Loch Lomond or just take the sun. There were of course references to war-time organisations such as the Soldiers & Sailors Families Association and the regular British Red Cross fund-raising events.

Perhaps the most unexpected event on the home front in the Vale during the War was the purchase of Balloch Castle and Estate by Glasgow Corporation. It was perhaps the one single tangible effort to create a “Land Fit For Heroes”. The Glasgow Councillors (helped by Alex Wylie of Cordale amongst others) who pushed the sale through in the face of some determined opposition, had started off being influenced by the River Leven Rights of Way protests and graduated to being determined to having a national amenity available for returning soldiers and sailors. It was one of the ironies of the war that the official opening of the Park took place on Saturday 1st July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, a day on which the British Army sustained 60,000 casualties.

A Collection of Photographs from France and Flanders. Walter Bisland, a noted local historian of Dumbarton and its people has very generously made available to the web-site a collection of photographs of towns and battlefields in northern France and Flanders taken immediately after the war. We don’t know for certain who the photographer was but it seems possible that she may have been the woman who appears in a few of the photos. She was working for a voluntary organisation, probably the YMCA, at this time and put her spare time to good use in recording the destruction in the towns and battlefields of the area. She seems to have had a Dumbarton connection through which they were given to Walter many years ago. Since then he has been searching for a suitable means to bring them to a wider public and we are delighted and thankful that he has chosen the valeofleven.org.uk website. The photos will appear in articles, including this one, but will also be shown in their entirety in the near future.

Note on Vale, Renton, Luss, Kilmaronock or any of the other Vale of Leven towns and villages. It would be too cumbersome throughout these pages to always refer to all of the communities from which men and women came. As strong advocates of the retention of correct local identities, we are conscious that in this and other WW1 articles we will sometimes use the term “The Vale” to encompass communities which are not part of the Vale and certainly do not regard themselves as part of the Vale. Please bear with our occasional failure in accuracy in this case, otherwise the articles would become difficult to write in places and even more difficult to read.

Next: A summary of WW1's Impact on the Vale >