Overview of the Impact of the War on the Vale

Introduction Page 2

Britain declared war on Germany at 11 o’clock in the evening of Tuesday 4th August 1914 and that same evening the King issued a proclamation that the Territorial Force had been “embodied” i.e. that all its members were required to report to their HQ – in this case Dumbarton. In expectation of the declaration of war there had been great civil and military activity in the town all day with khaki and the tartan of the soldiers kilts commonplace in the streets. By Wednesday 5th August 1914 the members of the Territorials in the Valley were making their way to Dumbarton with members of other units such as the Royal Garrison Artillery, who were the Clyde’s designated defenders, having to make their way further afield.

War had come to the Vale. In fact for many Reservists it had come a few days earlier and they had left to rejoin whatever unit they had previously belonged to. There were many men from the Vale and Renton already serving in the Regular Army as it was preparing to transfer to France. They were now being joined by many former comrades who had completed a spell in the Regular Army, had rejoined civilian live, married, found well-paying jobs (at least in comparison to the Army) started to raise families but had also been serving in the Army Reserve. The immediate impact on their lives were two-fold: not only were they being taken away from a settled family life but also their families could expect to suffer a dramatic fall in income as they switched from civilian to army pay.

War had come to the Vale. In fact for many Reservists it had come a few days earlier and they had left to rejoin whatever unit they had previously belonged to. There were many men from the Vale and Renton already serving in the Regular Army as it was preparing to transfer to France. They were now being joined by many former comrades who had completed a spell in the Regular Army, had rejoined civilian live, married, found well-paying jobs (at least in comparison to the Army) started to raise families but had also been serving in the Army Reserve. The immediate impact on their lives were two-fold: not only were they being taken away from a settled family life but also their families could expect to suffer a dramatic fall in income as they switched from civilian to army pay.

Since no Territorial or New Army unit was deployed at the front until the spring of 1915, all of the casualty reports until about February 1915 refer to men either from the Regular Army or Reservists who had rejoined their Regular Army units. These Casualty Reports tell us two things which are striking about the Reservists from the Vale: firstly how many of them were married with families (this wasn’t quite so true with Regulars) and secondly, how many of them did not work in the Vale. This contrasted with the Territorials, the majority of whom appear to have worked in one of the 8 textile finishing factories. The Territorials occupations can be explained by the long association between the factories and the local volunteer companies of which had been funded by the local factories, officered by the management, and whose other ranks had been encouraged to join by the factory employers.

Reservists on the other had mainly worked in the Clydeside yards and factories. The largest single group of them worked at Beardmore’s Yard at Dalmuir, with the Denny’s and McMillan Yards in Dumbarton close behind. John Brown’s Yard and Singer’s Sewing Machine Factory were also well represented. It’s perhaps not so surprising that men leaving the Army went to work outside the Vale, because in the years immediately before the War the Vale factories had been suffering from economic problems and strikes so there may well have been no jobs there anyway or they were not viewed as a good place to work. The system of exemptions was not yet in place in the very early stages of the War; otherwise it’s likely that most of the Reservists working in the Yards would have been granted exemption from serving. Given the desperate need for experienced men in France and Flanders and how touch and go the Race to the Sea against the Germans became, it’s probably just as well for the Army, but not for many of these men, that they were not granted exemptions.

Beardmore’s Fitting Out Berth Dalmuir

In fact, one of the most immediate consequences of the war in the Vale was that the textile factories went on short time in expectation of a collapse in demand in their markets. The Calico Printers Association Ferryfield and Dalmonach factories closed for Saturday 8th August and some days in week beginning Monday 10th August, making 1,000 people idle across the two factories. The 6 UTR factories also closed on Saturday 8th August because of the war, raising fears for the economic future in the Valley which had already been badly hit by the rundown of Argyll Motor Works.

400 people were actually still employed at Argyll Motor Works but their hours, too, were being cut back in August 1914 from 54 hours per week to 40. The working hours were:

Monday – Friday | 8.45 am - 12.45 am and then from 1.35 pm – 4.35pm

Saturday | 8.45 – 12 noon.

Singers Works, too, went on to short time working that week-end.

In fact the Argyll Motor Works soon became the Royal Naval Munitions Factory Alexandria, making shells for the Navy. It was the power-house of the local war-time economy with its inflationary wages, predominantly female work-force, and the demand for housing in the Vale from workers coming in from all over the country. In economic terms, WW1 was to become something of a boom time for many who remained at home in the Vale, a point made quite frequently and bitterly by correspondents to the Lennox Herald.

Many people who were not volunteering, nonetheless felt the need to do something warlike to protect the homeland and many people went up to the Alexandria shooting range on Millburn Muir to practice with firearms in the first few weeks of the war. This was entirely voluntary and unofficial and no equivalent of the Second World War’s Home Guard was formed during WW1, although home defence was entrusted to the Army Reserve and Territorial Forces. The practicing on Alexandria shooting range seems to have been a mixture of a “need to do something” and a show of solidarity with the young men who were volunteering.

One other quirky feature of the early days of the war was that the public were warned against using the River Leven after dark since armed Military Patrols were active guarding it. Similar patrols were seen on the Leven and Loch Lomond (as part of the River Clyde defences) during WW2.

However, the biggest impact of the War very quickly became apparent in the Valley as elsewhere – young men joined up to serve the colours.

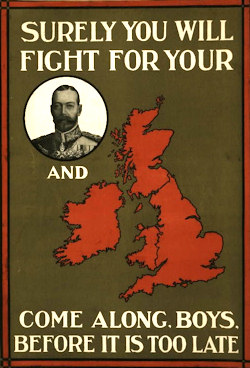

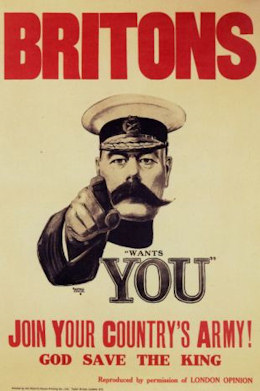

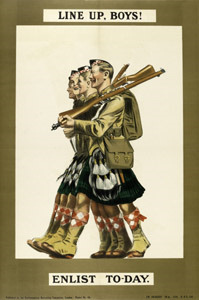

Recruitment - “Your Country Wants You”

The start of the recruitment campaign created the most famous British image of WW1 - Kitchener’s “Your Country Wants You” poster– which was released on 8th August 1914. Although the campaign got off to a slow start – there were only 7,000 recruits on 11th August – it soon picked up speed and on 3rd September 1914 33,000 men volunteered, the highest daily figure for the entire war.

The start of the recruitment campaign created the most famous British image of WW1 - Kitchener’s “Your Country Wants You” poster– which was released on 8th August 1914. Although the campaign got off to a slow start – there were only 7,000 recruits on 11th August – it soon picked up speed and on 3rd September 1914 33,000 men volunteered, the highest daily figure for the entire war.

So the recruitment drive of the late summer of 1914 quickly gained momentum and in the first 8 weeks of the war (i.e. the first week of August until the first week of October 1914) more than 750,000 men between the ages of 19 and 40 had volunteered to serve for 3 years or the duration of the war. Signing up did not necessarily mean the immediate departure of a young man to a regimental depot. Apart from anything else, the Army was overwhelmed by the number and was short of everything from competent trainers to uniforms and accommodation. So once they had signed up many young men went back home and waited to be summoned for duty, the wait usually lasting no more than a few weeks.

This wasn’t true, though, of one group of young Valemen – 13 members of the Vale of Leven Athletic Club had enlisted together and on the evening of 1st September 1914 they were all seen off amidst “enthusiastic scenes” at Alexandria railway Station by a large crowd of family and friends as they went off to fight for their country. Unfortunately none of their names were given in newspaper accounts so we don’t know who they were or what happened to them during the course of the war.

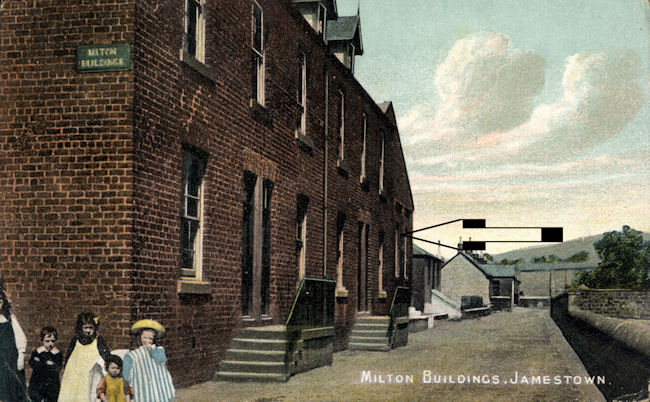

In the Vale and Renton, the four local Drill Halls used by the Territorials – in Alexandria, Bonhill, Jamestown and Renton - became recruitment centres manned by a recruiting sergeant who was usually a retired soldier. As the Battalion Head Quarters for the 9th Battalion (the Dumbartonshire Battalion) Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, Dumbarton was regarded by the authorities as the main recruitment centre for the county and some Valemen did join up there. Others joined in Clydebank, probably because they worked there, and others in Glasgow. At least 2 men took the Balloch – Stirling train so that they could join up at Stirling Castle, the Regimental Headquarters of the Argylls, most probably to try to ensure that they would actually serve in the Argylls rather than in some other regiment where the Army felt the need for men was greater. The Lennox Herald reported on 3rd October 1914 that 45 men had already volunteered at Jamestown Drill Hall by that date.

Jamestown Drill Hall in Milton Loan (indicated by arrow)

The flow of recruits did remain at a reasonably high level for some time – at least until the battles of the spring and summer of 1915. Then the realities of the war, which had savaged the Regular Army battalions of the British Expeditionary Force that had landed in France in August 1914, also began to take their destructive toll on the Territorial units and those who had volunteered in 1914.

The Territorials and the volunteer battalions of Kitchener’s New Armies were committed to front line fighting for the first time in the early spring of 1915. They had spent at least 6 months training at depots back in Britain, but at this stage of the war the training was almost completely devoid of practical experience of trench warfare. Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the First Army in 1915, was forced to admit that the 51st Highland Division was still "practically untrained and very green in all field duties" when it was committed to front line duties in France.

By the time it got to France the local Territorial unit, 9th Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders no longer belonged to the 51st Highland Division, but it was part of it during the 6 months training period at Bedford which Haig condemned in such shocking terms. The Bedford training was mainly made up of marching about the parade square, not a skill in great demand in the battlefields of the western front.

Mike Taylor in his history of 9th Argylls writes: “On the night of 19/20th February 1915 the 9th Battalion sailed to Le Harve and was soon engaged in the Ypres Salient, attached to the 81st Brigade, 27th Division. On 10th March 1915 the Battalion took its first casualties, with 5 men wounded. 10 days later a Corporal MacKay became the first 9th Argyll to be killed in action. For the first two months of their posting in Ypres the 9th’s casualties were relatively light, however it was then their turn to suffer.” The battalion certainly suffered; it was destroyed as a fighting force in May 1915 in the Battle of Festubert and its survivors dispersed amongst other battalions. This created a furore in Dumbartonshire but the 9th Argylls never fought again as a unit in WW1.

Early Reporting on the Reality of Life – and Death - at the Front

The horrors of the fighting at the front were reported with virtually no suppression of the facts by the Dumbarton and Lennox Herald almost from the start of the war. On October 10th 1914 the Lennox quoted a Renton soldier who was home wounded. He didn’t want to be named but he was one of 5 brothers with the colours, which as we’ll see later, narrowed it down to three families at that time. His brother had also been wounded as had another Rentonian serving in his battalion, Sydney Mayhew of Lennox Street; Mayhew had been badly wounded and was progressing as well as could be expected. The anonymous soldier said that he couldn’t credit the amount of destruction there was and after describing the hard fighting he said that he was glad to be back in his home village. That yearning to be home remained a constant theme with all of the soldiers throughout the War.

Destruction in Lens, from the Wattie Bisland collection

A letter from the front in the Lennox of 17th October 1914 also described the destruction, how hard the fighting was and how bad the conditions. It was from Private William Perry of Campbell Street Bonhill who as a Reservist had been called up to rejoin his old Regular Army Battalion, 2nd Argylls. He had been wounded and the regiment was having a hard time. He was soaking wet most of the time with no means of drying out. He didn’t think the war would last long, which was probably as much a wish as a forecast.

An even more graphic account of the fighting and the conditions appeared in an anonymous letter from another soldier serving in 2nd Argylls in the same edition of the Herald. Under the headline “An Arduous Campaign” the writer describes how 55 men went out to guard a railway line in case the Germans came. 7,000 Germans did come and “mowed the Argylls down like sheep”. Only 18 men came back. The soldiers went 15 days without dry clothing, being soaked from head to foot. It was not a picnic and he wished it was all over.

Similar stories continued to appear in the two Heralds from now on and we’ll publish many more. These two papers gave a true picture of what soldiers were suffering at the front so no one in this area, who was thinking of joining up, was ignorant of what faced them at the front. People volunteered for many different reasons, of course, including boredom with their present circumstances, improvement of their finances, patriotism, peer pressure created when all their mates were joining up and sympathy for Belgium, a small country being invaded by a large country, Germany, which like Britain had promised to help protect it. Any of these reasons could have overridden the knowledge of what lay ahead. Local historian John Agnew, who was a young man at the time, was certainly in favour of the war and wrote of the patriotic enthusiasm for it which he witnessed in the Vale as men joined up.

He doesn’t say how long this enthusiasm lasted but perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that volunteering held up as long and as well as it did. In spite of the carnage of 1915, recruitment still ran at a rate of about 100,000 men per month throughout the year. However that was not enough to replace losses and build up the new units required for the campaigns which were planned for 1916. Conscription seemed to be the only answer but the government tried to postpone the inevitable for as long as possible. In 1915 it introduced a half-way house between volunteering and conscription, under which men “attested” their willingness to serve. This became known as the Derby Scheme. It was accompanied by a system of exemptions from service, never gained any credibility and was soon deemed a failure. It was, therefore, only a question of time before conscription was introduced, which it duly was in January 1916.

Conscription

The government had already taken some steps to find out exactly how many men were eligible to serve on the basis of age alone (the upper age limit had been raised in May 1915 from 38 to 40). In July 1915 it passed the National Registration Act to discover how many men there were between the ages of 15 and 65 serving in a broad range of trades. All those between these ages who were not already in the services were required to give details of their employment.

The government had already taken some steps to find out exactly how many men were eligible to serve on the basis of age alone (the upper age limit had been raised in May 1915 from 38 to 40). In July 1915 it passed the National Registration Act to discover how many men there were between the ages of 15 and 65 serving in a broad range of trades. All those between these ages who were not already in the services were required to give details of their employment.

he results were available by mid-September and showed that there were about 5 million men in that group of whom about 1.6 million men were working in “starred” occupations i.e. occupations which were viewed as vital for the war effort and which men would not be allowed to leave to join the services. So on the face of it there was a pool of 3.4 million men to be called up, but of course a large part of that was over the upper age limit of 40 years of age.

Parliament passed the Military Service Act in January 1916 which introduced Conscription. The Act meant that all single men between 18 and 41 years old were liable to be called up for military service, unless they were widowed with children or ministers of a religion.

The Military Service Tribunals and Exemptions

There was a system of Military Service Tribunals to adjudicate upon claims for exemption upon the grounds of performing civilian work of national importance, domestic hardship, health, and conscientious objection. The law went through several changes before the war ended the most important of which were:

- Married men were exempt in the original Act, although this was changed in June 1916.

- The age limit was eventually raised to 51 years old

- Consideration was being given to lower the younger limit in 1918.

Conscription lasted until mid-1919.

The exemptions from service, which were a prominent feature of the Conscription Acts of 1916, had one hard-to-believe, but true, consequence: there were fewer recruits to the forces in 1916 with conscription than there had been in 1915 without it. Exemptions were the main cause of this drop in numbers. It was only by tightening the definition of “work of national importance” in the later stages of the war that the impact of exemptions was reduced.

In theory Exemptions could only be handed out on an individual basis after each individual’s case was considered by a Military Service Tribunal. These Tribunals were localised, usually with one per County. The local Military Tribunal met on a regular basis at Dumbarton Sheriff Courthouse. The numbers who served on it varied, but it was usually 4-5 establishment figures such as retired military men, lawyers, business men and the occasional Sheriff. They heard individual applications for exemption from service and in the Vale most applications came from family businesses such as shops, farm workers and even on one occasion a Vale publican – he had no luck in spite trying for exemption a number of times. By and large exemption applications by individuals were refused, although one man who was a stoker at Alexandria Gasworks was successful in his application because the Gasworks supplied gas to the RNAF. However, in the case of the Royal Naval Ammunitions Factory itself and other factories and yards working in direct support of the war effort, the Tribunal did grant “group” exemptions to the people who worked there, rather than hear each case individually.

Exemptions were in all cases only granted on a temporary basis and at the discretion of the Tribunal, so that during 1916 the Tribunal did withdraw exemptions from many young men who were working in the RNAF; the men were replaced in their jobs by young women. There then arose a common complaint that these young men, instead of going off to serve in the Army, simply moved up to Clydeside and got a group exemption from a shipyard or engineering factory.

Anyone wanting to change from one protected job to another also had to apply to the Tribunal, which could consider any objection from their current employer. Perhaps for this reason not many locals did apply to change jobs. However, a number of Belgian refugees, who were also covered by the Act, did apply to move out of the Vale. They mostly wanted to move down to the London area where there was a large Belgian refugee presence, particularly in Richmond-on-Thames. One Belgian wanted to move to Paris. All of the Belgian requests mentioned the rainy weather and how it was giving them rheumatism as the main reason for why they wanted to move and all applications to move were granted.

In the Vale the whole question of exemption from serving in the armed forces became a bitterly divisive issue from the middle of 1915 onwards. This was because much of the public perceived that there were many young single men working in the RNAF and there was a strong feeling that these jobs should go to married men with families, particularly married men who had been discharged wounded or incapacitated from the armed forces. Since the shells being made there were for use by the Royal Navy, the factory had come under the control of the Admiralty, but continued to be managed by Armstrong Whitworth. The Admiralty’s direct involvement gave an edge to the many complaints, since the complainers were criticising a government department which was actually fighting the war and which could not just ignore the complaints, which the Admiralty would clearly have preferred to do.

In the Vale the whole question of exemption from serving in the armed forces became a bitterly divisive issue from the middle of 1915 onwards. This was because much of the public perceived that there were many young single men working in the RNAF and there was a strong feeling that these jobs should go to married men with families, particularly married men who had been discharged wounded or incapacitated from the armed forces. Since the shells being made there were for use by the Royal Navy, the factory had come under the control of the Admiralty, but continued to be managed by Armstrong Whitworth. The Admiralty’s direct involvement gave an edge to the many complaints, since the complainers were criticising a government department which was actually fighting the war and which could not just ignore the complaints, which the Admiralty would clearly have preferred to do.

Terms such as “shirkers” and “cowards” became common parlance in the Vale, and Bonhill Parish Council joined in the attack. These complaints to ministers eventually did produce results and the numbers of young men were dramatically reduced. However, they were mostly replaced by young women rather than married men or former servicemen and that sparked another round of complaints about high wages, wage equality of women, women’s fashions, dancing – you name any social convention and some grumpy old Valeman was drooling off a letter to the editor of the Lennox about the goings on in the former Argyll Motor Works.

On one issue the complaints were entirely correct – the inefficient management of the factory which was not only incompetence but verged on fraud. Through the local MP the matter was raised in Parliament and the Ministry of Munitions sent an Admiral to investigate. The Admiral found nothing amiss and now we’ll never know whether he was also incompetent or knew that he was intentionally writing a whitewash report. In the 1920s in a Court of Session case based on payments from the Admiralty to Armstrong Whitworth and Argyll Motors the judge decided that there was substantial malpractice in the factory and overcharging which really was fraud. The BPC’s charges on that score at least were vindicated, albeit far too late. However it was the Admiral’s visit which seems to have been the trigger for the shake-out of young men in the Factory.

There was a need for some degree of Exemptions and that was most strongly recognised by David Lloyd George who became a highly successful Minister of Munitions after the Shell Crisis of 1915 and Prime Minister in December 1916. Although Britain was still a very strong industrial nation in 1914 and although it took some time to re-adjust, by 1916 industry was very much on a war-time footing with munitions production. It had to be, because for the first two years of the war Germany alone was out-producing all of its enemies put together in munitions and armaments. If that continued, then there was no way that Britain and France could hope to win the war, so the system of exemptions for the best of the craftsmen in the munitions and shipbuilding industry was valid. However, it was open to abuse and the levels of exemptions seen in 1916 could not be, and were not sustained

No class divide in the Volunteering – Nor of the Pain

It wasn’t only young working men who volunteered, it was also the middle and upper classes the great majority of whom joined up straight from public schools and universities. As a result WW1 was the first war in which the pain and losses were shared pretty evenly across all classes. In the valley of the Leven and on the shores of the Loch it wasn’t just Back Street, Burn Street and Random Street in which virtually every household mourned. Virtually every mansion in the area saw a family member killed or wounded including:

- Strathleven House – the Crum-Ewings lost a son

- Tullichewan Castle – the Campbells lost a son at the Battle of Jutland, at 16 years of age one of the youngest local men to be killed – there was at least one other 16 year-year old from Renton

- Woodbank House – the Ewing Gilmours lost a son

- Auchendennnan House – the Chrystals lost a son, and we will publish Mr Chrystal’s eulogy at his son’s memorial service as a fine example of mourning transcending background in the suffering brought on by wartime loss.

- Boturich Castle – the Findlays lost a son who was killed in the Gretna Rail Disaster.

This shared pain and sorrow across the classes lasted throughout the war as the loss of so many young men and the maiming of even more was carried to every street and hamlet in the area. A particular torture for many families was for a serving relative to be posted “missing” and for those at home to be left wondering, sometimes for many years, whether their loved one was alive or dead. Sometimes they did turn up alive, more often than not they did not and their relatives were left with a name on a battlefield memorial as the only record of their loved one’s fate, and sometimes not even that.

The Political Impact of the War

Being the first war to be conducted on an industrial scale, the War was also the first one between nations to have a huge impact on the home front, socially, politically and economically. It occurred at a time when many social and political movements for change were gaining momentum in Great Britain – women’s suffrage, the rise of the Labour party in politics, the emergence of strong trade unions in the work-place. These forces for social change were, somewhat paradoxically, happening at a time when Britain was at its height as a colonial power and when the ethos of “King, Country and Empire” was still a potent force in most people’s thinking.

Elections were suspended for the duration of the war at both national and local level. So the Bonhill Parish Council which was elected in 1913 served throughout the war until local elections were held in 1919. The 15 Councillors were predominantly Conservatives, mainly small businessmen, although there were one or two trade unionists also elected. The Council failed miserably on the first major war-time task it set itself – the drawing up of a Roll of Honour to record every man from the Parish who was “serving with the colours”. However it did much better on matters relating to its “bête noir” - the Royal Naval Munitions Factory.

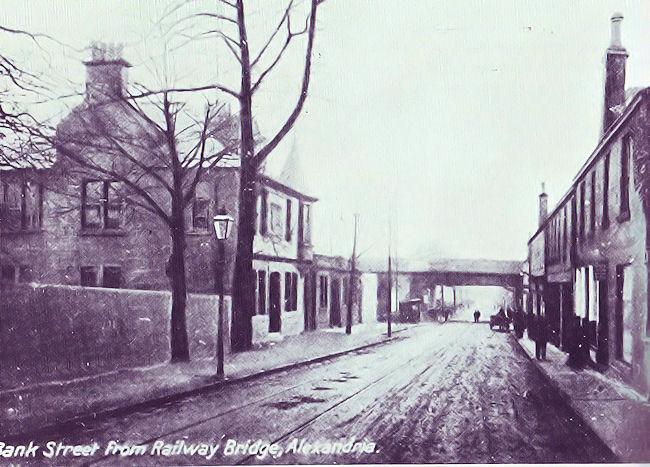

Constitution Club Offices of Bonhill Parish Council, Bank Street

Councillors had no qualms about taking matters on which it felt strongly to the highest level in the land and these matters nearly always involved the Royal Naval Munitions Factory in some way or another. The Councillors were unrestrained when speaking on matters such as shirkers or a lack of work in the Factory. They were just as forthright in their condemnation of replies and reports from government ministers, whenever the Councillors thought that the replies were unsatisfactory – which was most of the time.

In the 1919 local elections a few more left of centre councillors were elected and although it was certainly a more divided council than the 1913 one, the left didn’t make anything like the gains which the Independent Labour and Labour Parties were making on Clydeside. Until the 1922 election the Vale was still a safe haven for what its opponents called the “wee bourgeoisie”.

The Rolls of Honour

The monumental task of trying to identify the people of the Valley of the Leven who “served with the colours” during WW1 is made much more difficult by the failure of Bonhill Parish Council to carry out the task which it set itself early in the war of doing exactly that in the form of producing a Parish Roll of Honour. At that time a Roll of Honour was a list of men who served in the forces. It was only after the War that the title was taken to mean a list of those who were killed in the War. We describe this failure and the preparation of other Rolls of Honour in an article below on Rolls of Honour. It is no surprise that Renton takes pride of place with its first Roll of Honour.

The first thing we would like to have known for certain was just how many men served. The second is how many were wounded. And while we do have a fairly accurate figure from the 4 local war memorials of how many were killed – 559 – that is not a completely accurate figure either.

So we’ve had to make some rough calculations about the number who served and the numbers who were wounded. The methodology which we used was as follows:

- Numbers who served – This is a simple calculation based on the area’s share of the total Scottish population and multiplying that percentage by the official figure of the total number of Scotsmen who served in the British forces during WW1. The 3 parishes and Renton represented 0.0046% of the total Scottish population at that time while 690,235 Scotsmen served during the war. On that basis the number of local men who served in the British forces was around 3,175.

- Numbers wounded - There is a reasonably accurate correlation between the numbers killed and the numbers wounded in the British Army during WW1. Approximately 2.3 soldiers were wounded for every soldier killed and that would mean 1,280 Vale men would have been wounded during the war. These are raw figures, however, and record a wounding rather than the number of men who were actually wounded (many men were wounded more than once and some of those who had been killed were also wounded at least once before being killed.) So the number of men wounded was almost certainly less than 1,280, because as we’ll see many Vale men were wounded more than once.

Next: Men Who Marched Away - Joining Up in the Vale >