The Vale Empire Theatre

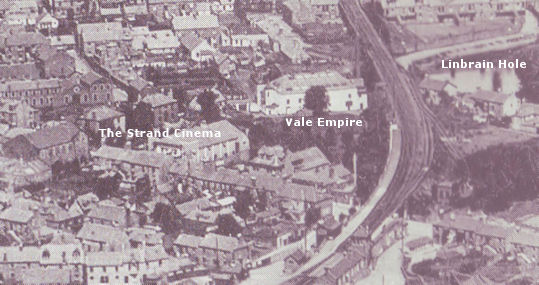

Steven Street Alexandria

1910-1930

For about 20 years in the first part of the 20th century the Vale had its very own variety theatre, famed and much loved throughout the area – The Vale Empire. It stood at the bottom of Steven Street backing onto the railway line, where the Co-operative Funeral Parlour now is and was converted for use as a theatre from its previous use as a chemical or dye-works. The Vale Empire was the creation of a bit of visionary who, as well as being a successful Alexandria businessman, was also a passionate amateur actor – James Boyd. He built a modern up to date theatre with as much detail paid to the behind-the-scenes facilities as to the fitting out of what was a very comfortable auditorium.

The theatre opened its doors on Monday 29th November 1910 with Harry Taylor the Musical Director, Manager Walter Gilbert and, of course, the owner and creator James Boyd, being rewarded with a full house. November 1910 may seem a little late in the day to be opening a variety theatre, considering that moving pictures had already appeared in Scotland; but very few in Scotland saw things that way in 1910. The Empire prospered and although within 6 years or so it had compromised and started to show films as well as live acts, it remained predominantly a variety theatre right until the end.

Its demise was brought on by a mixture of the arrival of the talkies and the crippling economic conditions in the Vale in the 1920’s and much of the 1930’s, when unemployment varied between 30 and 40% for many years. The last show for which we can find a record is as early as April 1930, although there may have been a few shows later than that. Sometime in late 1933 / early 1934 it was demolished and a couple of years later the SCWS funeral department had a erected a garage, workshop and stores on the site.

Unfortunately no close-up photographs of the outside of the theatre seem to have survived, although it does appear in the first aerial photograph of the Vale taken in the mid-1920’s.

However a number of cast photographs from Amateur Dramatic Society shows, taken on-stage, have been provided by Jean Henderson, whose mother Rebecca Malcolmson appears as Queen Elizabeth I in some of them, while Jim Biddulph has supplied advertising posters for the Vale Empire films and stage shows in the 1920’s which he salvaged from his days of working for William McKelvie, the printer in Hill Street. We are very grateful to them both for making these photos and images available.

Entertainment in the early 1900’s in the Vale of Leven

From the formation of the Bonhill Instrumental Band in 1817 there had been a strong tradition of music and singing in the Vale in various bands such as the Cordale, later known as the Renton Band and the Jamestown and Vale of Leven Instrumental Band. Organised singing was well represented too with groups such as the Teetotal Choir formed in the 1850’s, and from that choir there was a pretty continuous line to the Tonic Sol Fa Association (1861) to the Vale of Leven Choral Union (c 1880) and by 1909 the Vale of Leven Operatic Society, which was formed that year.

To begin with, the musicians and singers had a strong abstinence and church streak to them with performances mainly given in church halls or at church or community events, but that gradually lessened as the 19th century wore on. Such Scottish music as there was would have been provided by the Vale of Leven & District Pipe Band or performed at the Highland Association which flourished in the Vale for much of the 19th century.

Amateur dramatics had a distinctly lower profile, but there were drama clubs in both Renton and Alexandria in the later decades of the 19th century, and again some of them were church based. The Vale of Leven Amateur Dramatic Club seems to have been formed before 1900.

Of the “singing saloons” and “free and easies” which flourished in the cities and larger towns of Scotland, not a cheep is heard in the Vale. The singing saloons were a sort of 19th century karaoke club, while the free and easies were slightly more organised mini music-halls which were the direct precursors of the go-as-you-please contests which were to become a staple of the Alexandria cinemas and the Vale Empire in the 1920’s and 30’s and whose direct descendants are to-day’s reality talent shows. It may look pretty brutal on television on a Saturday night, but imagine what it must have felt like in front of a no-holds-barred audience, usually exclusively male and drunk, on a wet Thursday night in the centre of Glasgow in the late 19th century.

Needless to say these saloons and free and easies were very much working-class reserves, looked down on, not to say despised, by the middle and promoted classes. Even if such establishments did exist in the Vale, there was absolutely no chance that they would make it into the histories of Messrs McNeill and MacLeod or the douce pages of the Lennox and Dumbarton Heralds – these were bastions of self-improvement and moderation. So we don’t know if any of the various Vale pubs of the late 19th century did offer a platform to would-be entertainers and thereby helped to establish a tradition of music hall performers. If they did, very few people seem to have risen through their ranks to grace the boards of the Vale Empire or any other theatre.

However there was a tradition of attending high-quality variety entertainment in the Vale from the 1860’s onwards after the opening of the Public Hall in 1862. The Public Hall housed many activities in its side rooms – the Mechanics Institute moved there from Dalmonach School, the Masonic Temple also moved into a side room there from across the river in Bonhill, lectures and smaller public meetings, weddings etc were all held there. The main hall could seat 1,200 people and was the principal venue for larger meetings and entertainments. Apart from political meetings at election time and protest meetings against the tolls on the bridges, which could be guaranteed to fill it to overflowing, the “House Full” notices usually only went up when variety acts were appearing there. Many of them were top-line acts of the day such as the Christy Minstrels, but the biggest crowd-puller was W F Frame.

Wullie Frame “The Man in the Know” was a Glasgow-born comedian and singer who went on to own his own theatre for a time before forming his own small touring company which he took all over Scotland and then into England including London. Until well into his career he remained a precentor in a Free Church in Glasgow – apart from anything else he loved the music – and he was a total abstainer. So he was very acceptable to the ”improvers” in Scottish society as well as to the masses. WF was the biggest Scottish star before Harry Lauder and he was the first Scottish performer to tour North America, which he did in 1898-99. While there he even found time to visit an old friend from Alexandria, a Mr Thomson, who was literally, as it turned out, on his death-bed when Frame visited him. That tour was a huge success.

Nearer home, his first appearance at the Public Hall was in the 1870’s and he was still appearing there during WW1. From the 1880’s he could fill the largest theatre in Glasgow, which would seat about 4,000, for weeks on end. At venues like the Public Hall, however, which he visited when he went on tour, Frame usually did 1 night-stand. He, his company, costumes and props would arrive by train at Alexandria Station on the day of his performance. From there he would make a royal progress to the Hall, greeting everyone and chatting to them all with a smile and kind word. He was a genuinely decent person who liked being with people and needless to say he was a very popular figure in the Vale. After his show to a packed house he would retire to his rooms at the Albert Hotel at the top of Bridge Street and he, the company, the costumes and props would all be on the platform of Alexandria station in time to catch the 8.56 train up to Glasgow the next morning and on to his next show.

Other touring companies came and went at the Public Hall on a fairly regular basis, but no one thought that it could be filled by variety acts every night. This was the typical scenario in the smaller Scottish towns as the 19th century came to an end. Every town had a public hall which had a platform, some back or side rooms which could act as changing rooms and many had a balcony. All of these facilities could be pressed into service as an ad-hoc, temporary theatre but for all concerned they were a substitute for the real thing and no one pretended otherwise.

However, by the first decade of the 20th century things began to change and there was quite a boom in theatre openings in Scotland, particularly in the industrialised central belt. By the outbreak of WW1 in 1914 it is reckoned that there were about 60 theatres in towns across central Scotland, of which there were 20 in Glasgow alone. Many of these were in towns similar in size to Alexandria, to say nothing of the larger towns, some of which had at least two theatres. Broxburn saw a 500 seat cine theatre, the Empire Palace Theatre, open in 1910, while in Mossend another cine variety theatre, the 850 seat Mossend Pavilion, opened a few years after the Vale Empire in 1912.

Considering how creative the theatre business is, not a lot of imagination seems to have gone into theatre names. “Empires” abounded from the late Victorian years onwards, some owned by the Moss Empires theatre chain e.g. the Edinburgh Empire Palace – but others such as the Cowdenbeath, Clydebank and Motherwell Empires were privately owned. Over time the Glasgow Empire become by far the most famous Empire and one of the most famous variety theatres in Britain. Perhaps the only part of James Boyd’s plan which lacked ambition was his choice of name, but the other choices made at the time were also pretty limited – Pavilions, Palaces, Astorias, Princesses - really very little of distinction.

Many of the new theatres that were opening were of the cine-variety type – in other words they catered for the showing of films from the outset, as well as for live acts. In practice, this meant only that they acquired a screen which could be rigged up on the stage and a projector to project the films onto the screen. They might or might not have also built a projection booth to house the projector and the projectionist. Boyd chose not to do that at the Vale Empire in 1910, but to concentrate on providing the best range of theatre facilities which were practical in the building and most appropriate for his target audience – which was the people of the Vale and Dumbarton. The nearest variety theatre to the Vale Empire was the Clydebank Empire (no relation whatsoever to the present cinema of that name in Clydebank) so he had no local competition for a variety theatre.

Also, at the time there was little risk in not catering for moving pictures, or as they were perhaps more accurately called, “flickers”. In 1910 movies were more of a curiosity than a serious entertainment - picture and projection quality were poor and the contents typically were a bit boring. The biggest drawback films had in competing with the live theatre was that they were silent and audiences did miss dialogue, songs and music. Most cinemas tried to overcome this by having musical accompaniment to films – sometimes a small orchestra but usually a pianist or organist. Their aim was provide music which added to the sense of what was happening on screen – fast for a chase scene, sad for melodrama etc. Live musical accompaniment lasted until the talkies, and there were many excellent accompanists, but it was a poor substitute for sound.

Silence wasn’t such a drawback for comics who relied on sight gags such as Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and the Keystone Cops, but when James Boyd was converting the former chemical works to a modern theatre, the great movie comedians of the silent era were still a few years away. Although it was also in 1910 that Joseph Wingate opened one of the first purpose-built cinemas in Scotland in Church Street Dumbarton – the Picture Palace, which eventually became the Rialto – it was live theatre which was reigning supreme and Boyd was aiming to cater for the whole range of performances that could be provided by live theatre. In the largest cities some of the theatres could afford to specialise either in serious drama, or musicals or music hall but everywhere else the theatres had to be multi-purpose, putting on melodramas one week, music-hall the next, a touring opera company and then a revue, with a go-as-you-please thrown in occasionally to give local talent an airing. Add a couple of local concerts, a couple of weeks of the local drama clubs and operatic society’s annual show, the annual pantomime and you had your year’s programme to suit every taste and hopefully attract enough paying customers to make you some money.

That’s exactly how it worked at the Empire – and for many years it worked very well. It couldn’t afford the top line actors, actresses or music hall stars of the day, but no one expected it to. Second or more usually third tier performing companies appeared, typically for a full week. These companies were owned by different agents and managers and Boyd used many of them, but he made most frequent use of those owned by the biggest theatrical circuit of the time – Moss. Moss Theatres were started in Scotland in the late 19th century by an Englishman, James Moss, and by the time Boyd started to use their companies it had one of the largest theatre chains in the UK - Moss Empires. The touring company arm of the business, Moss Players, could be relied upon to supply a bill every week which would keep the audience happy for just about any kind of show – plays, revues and pantos. So this was the background of demand and supply which Boyd saw as his great opportunity in the Vale.

Mr James Boyd, Auctioneer

In fact it was a double opportunity because not only did it make business sense but also it allowed James Boyd to indulge a great personal passion – the stage in all its forms. It’s given to very few people outside the aristocracy and the very rich to be able to indulge themselves by combining personal passions and business ventures, and even fewer of them are to be found in the Vale. But James Boyd was lucky enough to be one such person. He had been active in amateur dramatics in the Vale for many years and was part of a group including his close friends Charlie Aitken, Sandy Lees and Tom Moncur senior, who were to become the back-bone of the Vale of Leven Amateur Dramatic Society in the first couple of decades of the 20th Century.

In a move which had later echoes in Victor Kiam’s TV adverts for Remington Electric Razors – “I liked the product so much that I bought the company” and Kevin Costner’s film Field of Dreams “Build it and they will come”, Boyd backed up his personal pleasure with serious money. These were not the actions of a young starry-eyed boy. In 1910 Boyd was 48 years of age, and he was an experienced businessman, well versed in dealing with the Vale public.

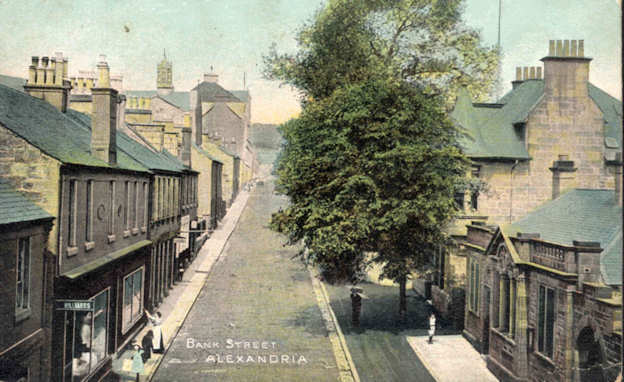

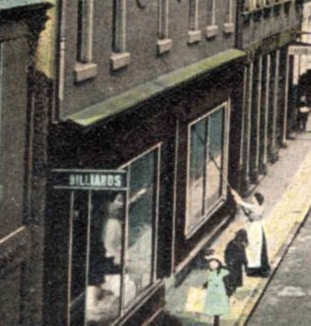

The Boyds were a long-established Vale family who at that time styled themselves as cabinet-makers and auctioneers. This meant that they made and sold furniture at a couple of locations in Bank Street. James  Boyd’s father, Andrew, had a workshop and a shop with a large frontage at 132 – 128 Bank Street in the building, demolished in the 1970’s, immediately opposite the former Post Office, now a dental surgery. In the photograph above (from about 1905) someone, possibly James Boyd’s mother or wife can be seen washing the showroom windows (bottom right), while the Billiards sign is also clearly visible.

Boyd’s father, Andrew, had a workshop and a shop with a large frontage at 132 – 128 Bank Street in the building, demolished in the 1970’s, immediately opposite the former Post Office, now a dental surgery. In the photograph above (from about 1905) someone, possibly James Boyd’s mother or wife can be seen washing the showroom windows (bottom right), while the Billiards sign is also clearly visible.

Further up Bank Street in what is now Bobby Biddulph’s carpet shop, he also had a work-shop and auctioneer’s rooms. As well as the shop and showroom, the Boyds also owned a Billiard Hall at 128 Bank Street – the sign Billiards in the accompanying photograph from about 1904 shows its location.

When Andrew died, his son James inherited the cabinet making and auctioneer’s business, and he was now in a position to pursue his passion for the theatre. However, becoming a theatre owner, manager and promoter didn’t mean that James Boyd relinquished these older businesses.He retained his interest in the business at 128-132 Bank Street, and indeed as owner of the Vale Empire he continued to style himself as an Auctioneer until his death in 1923.

The Empire did take most of his time and he rented 36 Bank Street out to another cabinet-maker, Peter Ewing. Thus a new name appeared on Bank Street, one which survived for another 50 years or so, later at a different shop in Bank Street, which Peter Ewing owned rather than rented, and after WW2 with a new owner, the Scotts. By that time the Peter Ewing’s shop was an ironmonger and although it survived another move, this time to Main Street, under its last owner, David Scott, it was closed by the mid 1970’s.

As well as his love for the stage, Boyd obviously had some insight into how to entertain the Vale public, or at least the male part of it, from his years of owning a Billiard Hall. Running a Theatre would be a lot more complex than running a Billiards Hall, but then again the potential rewards were substantially greater as well. Having the vision and passion to create a theatre was one thing, filling it was quite another. There were a few challenges to overcome, the target audience being the most important. The population for his immediate catchment area was only about 20,000 and while Dumbarton added another 20,000, distance no doubt reduced that potential.

As we’ve seen, by 1910 the era of mass entertainment was well established, but with the numbers involved in the Empire’s immediate surroundings it was important that no part of the community should feel excluded from attending a variety theatre, particularly on the grounds that it was “beneath” them. Mass entertainment in the Vale like many other parts of Scotland had already proved itself inclusive rather than exclusive and the main reason for this was football. In the 40 years before the opening of the Empire, football in the Vale had crossed all class backgrounds, such as they were in the Vale at the time. William Ewing Gilmour, head of the UTR and major benefactor to the Vale, turned up to support the Vale FC alongside the workers in his factories.

The House That Boyd built

Boyd had probably been thinking over the possibilities for a while, when in 1909 a potentially-suitable building became available. There is no definite date for the erection of the Stevens chemical works and while neither it nor Steven Street appear on the first detailed map of the centre of Alexandria dated 1860, they are certainly there by the 1880’s. The building which is variously described as a chemical factory, a colour factory and a dye works, was owned by Hugh Stevens, who lived in nearby Oakbank House, and after he died by his sons Daniel, Hugh, and David. Stevens Street in which the works stood, was named after the family.

The Stevens chemical works’ principal output was dye-stuffs for the local bleaching and dyeing factories such as the Craft, Levenbank, and Dalquhurn etc. These dyes only supplemented what the textile finishing factories – famed for their Turkey Red dyes - produced themselves, so it was never core to their business. From the time in the 1870’s when the German chemical industry and BASF in particular devised modern dye-making processes and dyes which were much cheaper, more reliable and attractive than the existing ones, these smaller dye-making businesses were living on borrowed time. As it turned out, the newer dyes had serious longer term consequences for the whole Vale bleaching and dyeing industry but that was not immediately apparent to most in the industry.

The Stevens works wasn’t the only such small manufacturer in the area to succumb to the new German chemicals. Turnbull’s Pyroligneous Works at Millburn had closed by 1900 and their Balmaha works followed not long afterwards, while the Chip Mill at Jamestown had closed even before that. There is no definite date for the closure of the Stevens works, but it and Oakbank House are shown as “Empty” on the Valuation Roll of May 1909. By 1909 the Stevens’ contact address is given as Jarrow so they seem to have left the area shortly after the closure of the works.

James Boyd bought the empty works (and Oakbank House which became his home) soon after they became empty and immediately set about converting the building. A redundant chemical works is not perhaps the most promising starting point for a new theatre – no new uses were found for either Millburn Woks or the Jamestown Chip Mill, which were both demolished. However, the Vale Empire building was quite new, and as other renovations in the Vale have shown over the years – the flats in the former Levenbank Works at Dalvait Road, Balloch, Antartex in the old Craft and the Dalquhurn Shop – these former factory buildings did prove amenable to even extensive alterations. Boyd’s experience and knowledge as a cabinet-maker helped him greatly in the physical conversion – building an auditorium including a main balcony, side balconies and even private boxes, installing the seating, building the stages, fitting out the changing rooms, installing footlights, spotlights and stage lighting etc. The one thing he doesn’t seem to have got quite right first time was the heating in the auditorium and in March 1919 he was announcing that he was replacing it with one of the most up-to-date heating systems in the West of Scotland, so it must have become an issue by then.

But his experience was no doubt of even greater value in the behind-the-scenes stage management department such as having a workshop in which to build scenery sets and props and carry out routine maintenance, and all the back-stage paraphernalia such as overhead gantries, pulleys etc which are a fundamental requirement of the professional, multi-purpose variety theatre and which separate it from the ad-hoc arrangements of the town or village hall. The Vale Amateur Dramatic and Operatic Societies in particular loved the chance to play in the “real” theatre which the Vale Empire became.

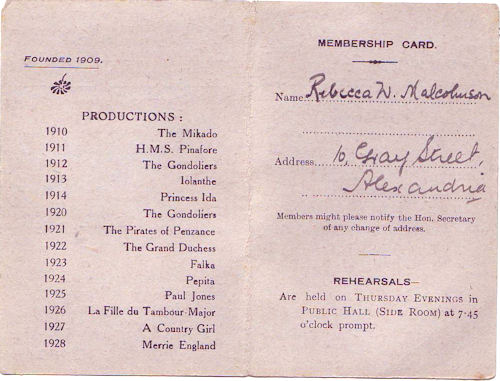

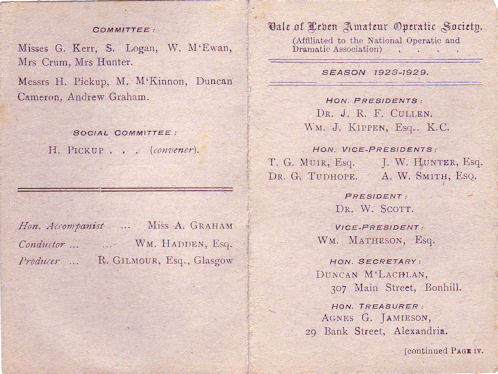

Rebecca Malcolmson’s Operatic Society’s membership card listing dates and shows

Rebecca Malcolmson’s Operatic Society’s membership card showing office bearers

By the autumn of 1910 Boyd had converted the former chemical works to a 1,200 seat working theatre. That was broadly in line with the capacity of the Empire’s local competitors – The Public Hall opened in 1862 with 1,200 seats and although that was later reduced when more comfortable cinema seating was installed, it was increased back to about 1,200 by extensions in the late 1950’s. When the Palace (later the Strand) Cinema was opened by Joseph Wingate in 1914, its capacity of 1,000 seats was similar to the other two venues in Alexandria. Nor, as we’ve seen, was the Empire’s capacity much different from other theatres opening in central Scotland at the time, or from the second tier Glasgow theatres of the day. A useful comparison in to-day’s terms is that the Glasgow Pavilion has approximately 1,800 seats.

The seating layout was also similar to that of many Glasgow theatres of the time, while the prices definitely reflected what the better seats were in the Empire, although of course what was a good seat near the front for a live act wasn’t necessarily a good seat for a film, and that too is reflected in the pricing:

Seating Areas Mid 1920s prices Mid 1920’s Prices Play / Revue Film

- Pit 6d 4d

- Area 6d

- Orchestra Stalls 1/3d 8d

- Side Balconies 1/- 9d

- Centre Balconies 1/3d 1/-

- Dress Circle 2/- 1/3

- Private Boxes 10/- not use

As we will see in the adverts for their shows, the prices for the Vale Operatic and Dramatic Societies’ shows were a wee bit higher than that.

Curtain’s Up

By the late autumn the Vale Empire opened its doors for business with Mr James Boyd, Auctioneer, as the owner and James Boyd & Sons as the operating company. From the outset there were performances once nightly, Monday to Friday, usually at 7.30 or 8, and twice on a Saturday – sometimes a matinee at 2.30 and an evening performance at 8 pm, at most other times a performance at 6.45 and another at 9pm. Until WW1 there were no shows on a Sunday and even when that rule was relaxed, any Sunday evening show was usually a concert in aid of war charities. Sunday evening concerts did re-appear in the 1920’s but again they were usually raising funds for charities or local clubs.

We don’t know the exact opening date of the Vale Empire or any other details of its first night, because the local newspapers carried no reports of it, and Boyd placed no adverts in the newspapers at the time – the two could well have been connected. Perhaps posters were used as the primary means of advertising the opening and the early shows. Boyd made liberal use of window posters, and almost right from the start the Vale Empire also had its own advertising hoarding at the top of Craft / Alexander Street which announced each week’s programme. No doubt word of mouth played its part as well.

The first reference to the Empire in print is in the Dumbarton Herald of December 14th 1910 (the Dumbarton Herald was published on a Wednesday, the Lennox Herald on a Saturday; they were both owned by Bennett & Thomson and the Lennox was usually just a rehash of the Wednesday paper plus anything important which had happened since). It reported that on the evening of Thursday 15th December there was to be a benefit concert in aid of Vale of Leven Football Club, to “reduce the debt hanging on the Club”. The Vale FC being in dire financial straits was a pretty regular occurrence from the 1880’s onwards, so there’s no surprise in a benefit being held for them. Unfortunately no further information about who was appearing, how much money was raised etc was forthcoming in the following weeks, so we have no idea how successful it was. You could surmise, however, that it was a smart move by Boyd to hold the benefit in his newly-opened theatre because it would get him early goodwill and publicity.

Too much shouldn’t be read into the silence in the newspapers because in the early years of both the Empire and the two Alexandria cinemas nobody did much advertising nor was there much editorial comment about them or their programmes. That was to change during WW1 and from then until its last few months the Empire advertised regularly and reports on its shows appeared in the news pages on a regular basis, although there were some gaps in both over the years.

Showtime

The Empire provided pretty staple fare to the people of the Vale and the formula didn’t vary much over the years. Most of the Empire shows were provided by touring companies, some English some Scottish. Each company specialised in its own type of acts. Some put on plays, or more specifically melodramas of the drawing room, comic or whodunit variety – nothing highbrow. Indeed the phrase “whaur’s your Willie Shakespeare noo?” might have been specially written for Scottish variety theatre audiences like those found each night in the Empire. They were very much products of their time: none of these plays would be performed to-day and their titles and authors have long been forgotten, in many cases deservedly so.

They were put on by touring companies such as Moss’s Selected Players, Lodge Percy’s Repertoire Company and later PD Productions. The titles of the plays included “The White Slaves of London”, “Eliza Comes to Stay”, and the comedy “When Knights were Bold”. The actors and actresses who performed them were well enough known on the circuit and some appeared many times at the Empire such as Fred Glen and Mrs Renee Emerson. However most were jobbing actors hoping for a big break but in the meantime making a living, just.

What was true for them all was that they worked very hard for not much financial reward. Although they would have a week’s booking at the Empire it was quite rare for one play to run for a week. More commonly, there would be two dramas in a week – one playing Monday to Wednesday and another from Thursday to the two Saturday performances. Sometimes there would even be three plays in the week, each playing for 2 days with 2 performances on a Saturday. Then on a Saturday night or Sunday morning the actors were off again to their next venue, and by Monday the next company had moved in.

Classical opera proved very popular with Empire audiences and it was provided firstly by John W Ridding’s English Opera Company and from 1918 onwards J W Turner’s “World Renowned” English Opera Company sometimes appeared instead. Both companies had a core list of operas which included such standards as Rigoletto, Il Travatore and Faust but they did add many others over the years. The opera companies had a particularly heavy work-load because they usually gave three performances on a Saturday. J W Turner’s programme for Friday and Saturday 17th and 18th November 1918 was typical. Advertising themselves as appearing “direct from the principal theatres” they were finishing off a week in Alexandria with:

- Friday Rigoletto

- Saturday Matinee at 2.30 Il Travatore

- Saturday 6.45 and 8.45 Daughter of the Regiment

The cast must have been pretty tired by the end of the Saturday night, but the Vale’s appetite for opera would have done Milan proud.

The most frequent and popular type of entertainment at the Empire was the music hall revue. Apart from the bill headliners who were almost all singers or comics, there were any number of music hall performers who appeared at the Empire covering the full range of speciality acts including jugglers, acrobats, trapeze artists, magicians, even mind readers and of course the chorus girls / dancing troupes.

We’ve only found one instance of a speciality act topping the bill at the Empire, and that was in July 1916. This act was a lady minder-reader – I’Ada – who was billed as “a Novel Attraction...a lady with supernatural powers”. Her slogan was that “She Knows You. She Knows Everyone. She Knows Everything.” Who knows? Maybe she did; in any event the Empire was certainly not going to undersell I’Ada or any of their other acts. There is no record if the men of the Vale, who were very chauvinistic indeed at that time, thought the idea of a woman who knows everything was in any novel, which is probably just as well.

Pantomimes were an annual feature, but not always at Christmas – for instance in 1926 the panto was put on in March; it was called Santa Claus, but he was a very late visitor from 1925. Pantos usually ran for only one week at the Empire and they usually guaranteed sell-out audiences. In the early years the Glasgow actor / comedian / manager Jack McKenzie provided the panto entertainment, while in later years the panto company might even come from England – with some unpredictable results. Their titles have changed little over the years – Aladdin, Robinson Crusoe, Cinderella all appeared at the Empire, along with many others.

The Vale Empire in WW1

Virtually from the start of WW1 in August 1914 the role of theatres and cinemas in entertaining munitions workers, troops home on leave and the population at large was well understood by the powers that be. People’s morale was a constant concern, especially after the terrible losses started to mount up firstly in Belgium and France and then in the Gallipoli and Serbian campaigns. In the Vale, as in other places, there were additional tensions arising from what were seen by some of the public as the undeservedly good pay and conditions of the munitions workers, particularly those in the Armstrong Whitworth shell-making and filling factory in the former Argyll Motor Works. Many of these workers deeply resented this, of course, seeing themselves as engaged in difficult and dangerous work.

Entertainment helped to provide some release from the tensions of war and 1914 was a good time for Mr Joseph Wingate to have opened his new purpose-built cinema - “Wingate’s Picture Palace”, renamed the Strand in 1928. It lay within a few yards of the Empire as the crow flies, but a bit further to walk. Wingate, who styled himself as a “Showman” throughout his life, joined the Public Hall in showing films as the Palace’s main form of entertainment. The Hall had acquired a licence to show films in 1912 and was the first of the Vale’s full-time cinemas. In fact both the Palace and the Hall also had live acts to support their silent pictures until the arrival of the talkies in 1929. All of Alexandria’s 3 entertainment halls did good business throughout the war.

Virtually from the War’s outbreak in August 1914, the Empire hosted shows to support some aspect of Britain’s war efforts such as concerts to raise funds for the Red Cross, the Soldiers & Sailors Families Association, and Princess Louise’s new Home for Limbless Soldiers & Sailors at Erskine. During the War when Alexandria men received decorations for their valour, concerts were given in their honour in the Empire – as they also were in the Public Hall. In Renton the Renton Public Hall was the scene of even more such events to honour Renton’s many decorated war heroes.

The Empire’s programmes began to reflect the need for light relief and for patriotism, so the shows included more comedians and comic sketches as well as comedy plays and even westerns, which were something of an innovation. The press obviously understood the need to improve the public mood and that entertainment was an obvious way of doing this, so newspapers actively boosted theatres and the cinema. The Empire saw its profile rise in the two local newspapers, but even so a few eyebrows may have been raised at the Lennox Herald’s report of 9th January 1915 on the Empire’s upcoming pantomime, a report which could have been written by James Boyd himself:

“Mr Jack McKenzie’s pantomime will occupy the hall next week...Mr McKenzie triumphed last year with Cinderella but Robinson Crusoe is stronger still, brimming with droll sayings, expensive costumes, rollicking fun, special scenery, dainty dancing and sweet melodies. As the house will be full, seats should be booked early. Mr Boyd is to be congratulated on having secured this powerful attraction so early in the season.”

That seems to be what we would now call a press release, printed virtually unaltered in the Herald. On reflection it probably was written by either Jack McKenzie or James Boyd and in any event they must have been delighted at such a straight sales pitch appearing in the news section of the paper.

By April 1916 James Boyd had obviously decided to take things more easily; in fact it’s possible that he was already suffering from a serious long-term illness. He had been running his theatre for almost 6 years and he was 54 years of age, so he decided to hand over the management of the theatre to a younger man. In those days (and even now in some places) the theatre manager was not only a back-stage figure attending to bookings, advertising, building issues etc, but was also a very visible front-of-house personality who was expected to appear in the foyer at each performance in evening dress greeting the theatres patrons. It was a very demanding role and Boyd had certainly earned his break. He retained ownership of the theatre and the operating company stayed as James Boyd & Sons, but an outsider was introduced as the new manager or tenant or lessee, depending on the report – Mr Henry L Osmond.

Under New Management – for a while

James Boyd received a presentation from his staff on the stage of the Empire in April 1916 and handed the theatre over to what was described as “its new tenant”, Harry Osmond. Osmond was well known in the profession and no doubt it was a safe choice by Boyd at the time. Osmond quite rightly set about stamping his name on the theatre – quite apart from anything else it would have been expected of him. The first newspaper adverts after he took over had his name immediately below the Vale Empire banner:

“Lessee & Manager – Harry L Osmond”.

James Boyd had never done this and in fact Osmond’s name disappeared from the adverts after 3 or 4 months. Obviously since he had to pay rent for the theatre, attracting a big audience all the time was the top priority for Osmond. It is tempting to see his early programmes as lowering the Empire standards by trying to draw in the public to see shows with sexual undertones. His first couple of weeks included:

“The Girl in the Taxi” - a comedy play,

And the week after that

“The White Slaves of London” - described as being direct from the Glasgow Metropole, but everything else about it is left to the reader’s imagination.

However that’s probably stretching things a bit, partly because the standards of the Empire drama had never been particularly high and partly because Osmond soon returned to the tried and tested Empire formula. May saw a revue and by the end of the month “Mr Osmond goes back to drama by staging two western plays”. These westerns were something of a novelty in those days but unfortunately no details were given about them. By way of further innovation, it was also Osmond who put on the aforementioned I’Ada as the headline act in July 1916.

The Empire shut for a summer break which was the same as that taken by the local works. In those days this was not the Dumbarton Fair at the beginning of July, but was in August. When it re-opened right at the end of August with a play – “Eliza Comes to Stay” Osmond’s name had disappeared from the adverts and never re-appeared, although his name continued to be used in editorial content in the papers. In September he introduced “go-as-you-please” competitions which he advertised as being held every Thursday night. They didn’t last long at this time and were soon phased out, but in the last years of the Empire the go-as-you-please shows were a permanent feature and in some weeks in the late 1920’s they were the only show being put on at the Empire. They were, of course, very cheap to stage.

It didn’t take long before the Hall copied the idea and had “go-as-you-please” competitions as well - by 1917 the Hall was having them every Wednesday and Thursday. The Hall programmes were also mixing live acts with silent films. In September 1917 the Public Hall Pictures and Variety, as it styled itself at that time, had a week which combined a film “The Defence of Verdun” and the very welcome return of W F Frame. The Battle of Verdun, involving the French and Germans was fought for most of 1916 and was the bloodiest battle of WW1; it is still the embodiment of French patriotism and the grim defence of Verdun by the French drew huge admiration from the British public. The film “The Defence of Verdun” was a box office hit in Britain and combining it with live appearances by “the one and only WF Frame”, was something of a coup by the Hall’s management for although he had been somewhat eclipsed by Harry Lauder by this time he was still a great favourite in the Vale. Stealing ideas from each other is a given in entertainment and the Empire was to return the compliment to the Hall in a few years, as we shall see.

December 1916 was a busy month at the Empire with the re-appearance of John W Ridding’s English Opera Company which performed three operas during the week – Rigoletto, Il Travatore and Maritana. For good measure they were also putting on a Sacred Concert on the Sunday night in aid of limbless soldiers and sailors. There were a number of Sunday-night Sacred Concerts at the Empire during the war, all in aid of war charities. What distinguished them from any other sort of concert was simply that the music was religious or classical and any spoken pieces would also be of an “uplifting” nature. They seem to have attracted good audiences, especially since they began at 8 o’clock allowing people who had been at an evening church service to go straight from church to the concerts, and to help a good cause.

The other highlight of December 1916 at the Empire was the presentation of a play written by Harry Lauder – “The Night Before”. Lauder’s brother, Alick Lauder, appeared in a leading role which was no doubt an additional draw. The play toured extensively and by all accounts it was worth the attendance money with Alick Lauder turning in a pretty competent performance. This was followed by a comedy “Bauldy” and then into January 1917 with the annual panto.

The Empire panto in January 1917 was Aladdin and that is one of the last references there is to Harry Osmond at the Empire. By March 1917 it was announced that the Empire was under new management. There was no mention of Osmond’s departure but it was almost exactly a year since he had taken over and it is quite possible that he had signed a one year lease which was not renewed by one or other of the parties. There is a brief mention of a new manager, a Mr Harry Reeves, in August 1917, but he never featured in any of the adverts nor have we found any other reference to him. Ownership and operational control remained as before with Mr James Boyd and James Boyd & Sons respectively

James Boyd returns as manager

At exactly the same time as Osmond’s departure in March 1917, the Empire announced that it was going to start showing pictures as well as continuing to present variety shows and from 12th March 1917 the Empire began showing two serial pictures – a favourite device of the silent film and children’s matinee era. It was said that mysteries would also be shown. From then on it advertised itself as showing Variety and a Picture Program. Of course the Empire was as well equipped as any theatre or public hall to show silent pictures and no doubt this was partly a defensive move by James Boyd in response to the competition from the Palace and the Hall.

Movies had vastly improved both in terms of production and content, and a number of movie stars had emerged such as Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, so their popularity with the public had greatly increased. But money probably played a part as well. In comparison to live acts, hiring films was cheap – typically a third to a quarter of the cost of putting on a live act, and a lot less management effort as well. When showing an all-film programme seat prices had to be considerably less to reflect this, but the risk of financial loss was also considerably less with films. As it turned out, it was not until the mid 1920’s that the Empire announced a fairly regular weekly programme given over exclusively to showing films. Until then, when a film was shown, it was part of a program which included live acts, and was a supporting feature to the live acts.

Even after the change of management and the introduction of films, drama and revues remained top priority at the Empire. When it re-opened after its summer break at the end of August 1917, under the management of Mr Harry Reeves the first offering was one of the most popular shows of the day – Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This was sometimes presented as a drama, sometimes as a musical, and when it featured again at the Empire in 1927 it was presented by the Vale of Leven Dramatic Society (it made a 3rd appearance in a touring company presentation in 1930 as one of the Empire’s last live shows, so obviously it had some appeal to the Vale public). The 1917 show was a professional touring production whose main claim to fame was that it featured “Real Negroes”. The term “Uncle Tom” and the names of the two slaves who feature in it – “Sambo” and “Quimbo” – have now become politically incorrect and no one would dream of putting it on these days, but it was another product of its time and at the time no one saw anything wrong with it.

In December 1917 the Empire ended the year with another leading show of the time, the hit comedy “When Knights Were Bold” which was billed as coming “direct from the Kingsway Theatre London”. The first Lennox Herald of 1918 reported that “Mr Boyd scored a big hit this week......it opened with a big house on Monday and continues till the end of the week. Sir Guy and Lady Rowena received especially enthusiastic receptions”.

The following week Mr & Mrs Lodge Percy’s Repertoire Company were putting on 3 plays – “Moths”, “Under Two Flags” and “For the Love of Peg”. The same paper noted that the Public Hall also did exceptionally good business that week.

11th November 1918 saw the end of the War with the Armistice coming into effect at 11 o’clock that day. In the evening of the 11th November J W Turner’s “world renowned Opera Company, direct from the principal English Theatres” was performing at the Empire. The following week the Empire panto was to have been performed by an English company. It was Dick Whittington and was billed as a lavish production which included 45 Star Artists, but, nae luck, the scenery which was also coming up from the south of the border, disappeared en route. Such were the problems of running a theatre company in wartime. It wasn’t until the end of March 1919 that the Christmas panto was put on and it was Jack & The Beanstalk rather than Dick Whittington.

The next show at the end of November / beginning of December 1918 was based on arguably the best known humourous product of the WW1 – “The Better ‘Ole” by Captain Bruce Bairnsfather and Captain Arthur Elliott. Bruce Bairnsfather was an English humourist who came from an old military family. He became best known as a cartoonist and he continued drawing cartoons after he joined the army. He created a character called “Old Bill”, who was an old soldier serving in the trenches in France. As soon as he began to appear in Bystander magazine Old Bill, with his walrus moustache and balaclava, became a particular favourite with the troops and with the general public. Some Colonel Blimp, as clueless about morale as his colleagues on the General Staff were about fighting the war, wanted Bairnsfather to stop, but the War Department propagandists had already spotted Old Bill’s priceless value as the country’s favourite figure of fun, and he was very much encouraged to continue. His most famous cartoon involved Old Bill and another soldier who was complaining to Bill about the shell-hole they were sharing under enemy fire. “If you know a better ‘ole, go to it” was Bill’s retort. The punch line caught the soldiers’ mood and it became a catch phrase in the army and in Civvy Street as well. It has proved remarkably enduring, because the collected cartoons are still in print almost a century later.

The War Department spotted the opportunity to develop the material into a theatre production and “The Better ‘Ole” which was presented at the Empire was the result. It was a combination of a play, pictures and scenery “to create the actual situation in the battlefields of Europe to let those who had to stay at home see what their loved ones in the army had to endure”. No one was naive enough to believe that it came anywhere near that, of course, but people respected and enjoyed the attempt made by The Better ‘Ole to get even a little insight to what it was like and it played to full houses all over Britain. Ironically, by the time it got to the Empire the war had just finished, but that wouldn’t have lessened its impact. The complexity of the scenery and sets gives further confirmation of the sophistication of the Empire’s stage management capabilities.

The first months of peace saw the Empire continuing its usual combination of revues and plays. Having missed the panto, they put on instead a “Grand Auld New Year’s Night” around the date of the Auld Scottish New Year in mid-January. This was a Scots variety show plus pictures featuring such acts as the Four Scotia Lasses who offered “musical variety and dancers”, Watson’s Great Vocal Comedy, and Kitty Grey “Wonderful Juvenile Chorus Singer”. This was followed by what appears a very risqué week of plays put on by Rolla Balmain’s London Company

- Monday – Wednesday: The Misleading Lady, “direct from the Playhouse Theatre London”:

- Thursday – Friday: Sapho! “The rage of Paris”

- Saturday Ghosts, “by request and something new to the Vale, the play prohibited by the Lord Chamberlain for 25 years” (in those days a government figure, the Lord Chamberlain, vetted the script of every play put on in Britain)

By the autumn of 1919 the mood of the Empire’s offering had changed again, this time in a totally unexpected direction – it found religion. It advertised “Adult Programmes” which were exactly the opposite of what that term usually means – they were in fact morality plays which were offered in a two separate weekly programmes. The plays in the first week included “The Unborn – a photoplay”, “The Girl Doesn’t Know” and “Should a Woman Tell?”

In what also seems to have been a first for the Empire, there were no admission charges for the first week’s plays. Another first was that the plays were accompanied by a lecture – “a moral lecture” according to the advert. This was delivered in person by the Rev A J Waldron, who was the Vicar of Brixton in London. He was one of the best known churchman of the day and was what would later be called a trendy vicar.

Waldron didn’t believe that everything which appeared in the Bible should be taken literally but on the other hand, he fervently believed in confronting social issues of which there were plenty in his parish, and was therefore highly regarded by many public figures. He was the author of one of the short plays in this week’s program – “Should a Woman Tell?”, which dealt with the question of whether or not a woman should tell her fiancée of any “delinquencies” in her past life. No such question was addressed to men, but again that was typical of the times. The play was performed in a great many theatres, not just in the UK, but also in the United States and Waldron often went on short lecture tours with it. His appearance at the Vale Empire was quite a feather in the Empire’s cap.

The following week’s play was even more overtly religious. It was called “The Rosary” and performed by a London company under the direction of Jessie Millward, a famous serious actress of the late 19th and early 20th century. However she was probably even better known as the lover of one the leading actor-managers of the last years of the Victorian age, who was murdered by a deranged actor in the foyer of the Adelphi Theatre, London. If there was any contradiction in such a person putting on morality plays, then the public didn’t seem to either notice or be bothered by it. The plays in both weeks seem to have played to good houses, which is even more impressive when you consider that “The Rosary” was competing against the Queen of Hollywood, Mary Pickford, at the Palace.

The 1920’s

In the immediate post-war period the Empire continued with its formula of a mixture of revues, pantos and, on a reduced scale, dramas. Films played an increasingly large part in the Empire’s programs although James Boyd set himself apart from his competitors with an announcement in March 1919 that he had “decided to show nothing but class pictures” from now on. How that was received by Joe Wingate is unfortunately lost in the mists of time, but as we shall see the Empire did show a more serious type of picture than any of the other cinemas in the Vale. By the beginning of 1925 the Empire was advertising itself as a “Super Cinema and Playhouse” but by then many changes had taken place at the Empire.

The most significant of these was the death of James Boyd on the 8th January 1923 at his home Oakbank, almost adjacent to the theatre. He had suffered a long illness but his death at only 61 was untimely. Although the ownership of the theatre remained with the Boyd family until it closed, Boyd’s death brought a change in the operating company which ran the theatre. Until Boyd’s death this had continued to be James Boyd & Sons, but soon after it was changed to the Vale of Leven Premier Picture & Variety Company. This was not entirely a new name: in 1916 the Public Hall had advertised itself as the “Premier Picture & Varieties Theatre”, but as we’ve said, plagiarism is a cornerstone of the entertainment industry. It’s also possible, of course, that people from the Public Hall management of 1916 were involved with the new operating company at the Empire and simply took their slogan with them as the name for their new company.

Films and Variety Bills

Throughout the 1920’s the management pursued a policy of interspersing a week of films with a week or so of variety bills. Even when showing films an element of live entertainment was included. As the poster for the film The Nibelungs in October 1925 shows the Copeland Trio were appearing on the same bill.

Throughout the 1920’s the management pursued a policy of interspersing a week of films with a week or so of variety bills. Even when showing films an element of live entertainment was included. As the poster for the film The Nibelungs in October 1925 shows the Copeland Trio were appearing on the same bill.

Click the image to see larger poster >

The Hall and The Palace did likewise when showing films. The Hall in fact still put on separate live shows throughout the 1920’s e.g. The Glasgow Orpheus Choir gave concerts in the Hall so it kind of hedged its bets until the arrival of the talkies.

Not so Joseph Wingate at the Palace: it was a cinema and concentrated on showing films, and live entertainers were only there to support the films. As the decade wore on Wingate’s advertising got ever more up-beat and his coverage in the press increased. Without doubt The Palace had leadership over both The Hall and the Empire in that it showed the most popular films of the day.

By 1928, even in the difficult economic conditions, Wingate felt confident enough about the future of the cinema to close the Palace for major refurbishment. When it re-opened in late October 1928 the former Palace had been not only refurbished, it had been re-named The Strand and thereafter it styled itself as “Alexandria’s Super Cinema”. From that point onwards the Strand began to pose a major threat to the Empire, even if it had not done so before. It was now more comfortable and it had a better location standing on the main thoroughfare of Bank Street rather than at the foot of a side street which was pretty dingy on a winter’s night. Also, it was now equipped to handle the talkies when they came in 1929, and was therefore best placed to show the most popular films of the day.

The policy laid down by James Boyd in 1919 of showing only “class films” was continued by the Empire’s management throughout the 1920’s. The more serious movies of the day were favoured at the expense of the lighter, more popular films being shown by their competitors. Of course the Empire did show some of the more popular films but films such as “The Nibelungs” in October 1925 followed soon after in November 1925 by “Madonna of the Streets” predominated and that trend continued into the late 1920’s – as an example in February 1928 it was showing Jules Verne’s “Michael Strogoff”.

< Click the image to see larger poster.

These were not the first films you’d turn to for a bit of light relief. The Nibelungs was made by renowned German director Fritz Lang but it was a dark Nordic / Teutonic tale of the sort typified by the Richard Wagner operas – not in great demand in the Vale neither at that time, nor anytime soon. Similarly with the Madonna of the Streets. Its star was the exotic Alla Nazimova who was one of the leading actresses of the silent movie era, as well known in her day as Rudolf Valentino. However, she took herself very seriously as an actress and tended to overact, while the story itself was tear-jerker.

(Nazimova made so much money out of her early silent pictures that she built as her private house The Garden of Allah which was to become one of Hollywood’s more scandalous addresses in the 1920’s – 40’s. She then lost most of her money on films which she directed with disastrous results and she had to sell The Garden of Allah. It was converted to a small, exclusive hotel which became home to many stars in the 1930’s and 40’s whose behaviour at the Garden of Allah ensured that its reputation did not change.)

The content of the variety business carried on as before, only there was less of it as films and Go-as-You-Please shows displaced revues and plays. However, concerts in aid of good causes survived e.g. The Grand Benefit Concert in aid of the long-gone Vale of Leven Ornithological Society in October 1925.

The content of the variety business carried on as before, only there was less of it as films and Go-as-You-Please shows displaced revues and plays. However, concerts in aid of good causes survived e.g. The Grand Benefit Concert in aid of the long-gone Vale of Leven Ornithological Society in October 1925.

Click the image to see larger poster >

Touring companies continued to perform at the Empire right up until January 1930 but there were definite gaps in the appearance of live acts. Often those that did appear had to make way on a Thursday night for the regular Go-As-You-Please, which seems to have become the major financial prop for the theatre.

A typical selection of these companies included in early 1925 PD Productions which brought a revuette to the Empire called “The Cosmos”. It described itself as “songs, concerted sketches etc.” and was headlined by Scots comedian Jimmy Merrylees, who had appeared at the Empire many times before. Another favourite was Cora Corina who headed an all-star variety program in January 1928, and this was followed in February 1928 by a revue provided by a company calling itself the Perth (Scottish) Entertainers. Its programme was typically Scottish fare of songs, music, dancing and of course Scots comics.

From time to time plays made a re-appearance. In July 1929 Moss’s Selected Players were something of an exception in that their program of 4 plays was not interrupted by the Go-As-You-Please. The variety of the plays shows not only the dexterity of the players but also how hard the theatre management was working to attract an audience. The plays were:

- Monday / Tuesday “Charity” which is described as a drama

- Wednesday / Thursday “Jeanie Deans”

- Friday “Passion Hour” which is described as “an adult play” although that meant something very different in 1929 from what it would mean to-day

- Saturday “Charlie Peace or the Banner Cross Murder”. The advert said that Mr Fred Glen in the title role will be a special attraction, which could well have been the case because Fred Glen was one of the leading actors in the west of Scotland at that time.

As usual there was one house nightly at 8 o’clock, and two on a Saturday 6.45 and 9 pm.

By November the Empire was advertising a Go-As-You-Please every Thursday with prize money of:

- 1st Prize 30/-

- 2nd Prize 15/-

- 3rd Prize 10/-

These Thursday sessions were all that the Empire was offering during November and much of December 1929, with the exception of the Dramatic Club’s presentation of The Rebel Chief.

However in the last week of December and the first week of January 1930 it put on a Grand Annual Pantomime – Moss’s Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp. The cast for this included Mrs Renee Emerson, W E Moss, Fred Green, the comedian Harry Harold, and the Six Richmond Girls. There were no less than 3 performances of the show on New Year’s Day. Prices were 6d, 1/-, 1/3, which seem to have been quite low, but were probably a telling indicator of the economic circumstances in the Vale by then. (2.5p, 5p and 6p in today's money)

The pantomime was followed in the next week in January 1930 by a full program of plays again presented by Moss’s Selected Players, culminating in Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the Saturday night, which by our count was making its third appearance in the Vale, including the Dramatic Society’s offering. But even at that, Thursday night was given over to a Go-As-You Please. The last professional performance which we have been able to find at the Empire was on Saturday 22nd February 1930 when Marcella Albani appeared in a performance of The Tragedy of the Opera.

The Vale Amateur Societies at the Empire

Perhaps the most memorable feature of the Empire as far as many in the Vale were concerned was its use by two of the local performing clubs – the Vale of Leven Amateur Dramatic Society which dated back to the 19th century and the Vale of Leven Amateur Operatic Society which was founded in 1909. There were many people who were members of both clubs, and while the Operatic Society confined itself to light opera, the Dramatic Society or Drama Club, as it was also called, sometimes put on musicals as well as dramas.

Many of the members were prominent Vale folk. Doctors seem to have been attracted to honorary positions in the Operatic Society, while J Kippen, laird of Westerton House and Estate, was an active Honorary President of the Dramatic Society. Many of the names such as Lindop, Pickup and Fanning were prominent for the next 30 years or so in entertaining the people of the Vale, while the Dowds family produced not only music teachers but also the most prominent Musical Director in post-WW2 Scottish theatre – Bobby Dowds, of whom more later.

For all of these amateurs, being able to perform on stage at the Empire or work back stage there was a dream come true. They might have been amateurs, but the whole Empire environment was highly professional and they made the most of it while they could, which was just as well because it didn’t last all that long. Thankfully we have Jean Henderson’s photographs which give some indication of the scale and quality of the productions put on by these amateur societies. We also have a full list of the annual productions of the Operatic Society up until the Empire closed and we have pieced together some of the Dramatic Club’s productions as well, but by no means all of them.

Both societies rehearsed through the winter and put on shows in February / March and while one was enough for the Operatic Society, the Dramatic Society typically presented a second play in September / October.

The Vale of Leven Amateur Dramatic Society

His involvement with amateur dramatics was one of James Boyd’s reasons for opening the Empire, and the friends with which he had shared that passion remained involved with the Dramatic Society into ripe old age. Sandy Lees, who had a pub in Alexander Street, played the lead role in the Society’s production of the Scottish play “Rob Roy” soon after the end of WW1, when he was 70 years of age. The members were obviously doing it for the love of being on the stage and the Dramatic Society’s productions were always in aid of local charities, although they did not always actually make any money.

The 1925 production of “The Lady of Lyons” by Lord Lytton, which ran for a week in January 1925, was put on with high hopes. Ticket prices ranged from 6d to 3/6 and could be bought from C W Gilchrist at 112 Main Street, Alexandria and as an added incentive Gilchrist advertised a Great Crossword Puzzle for everyone who booked tickets from them. The show was produced by Charles Aitken who was the Club’s top director and the musical director was the well established Thomas Scott. An augmented orchestra and full chorus was advertised and to top it all the tram company was continuing its policy of putting on late cars from the Fountain each night to take show-goers home to Jamestown and Dumbarton. All of that looked, in fact still looks, like a solid foundation for a successful show.

A letter in the Lennox on 7th February 1925 tells a different story. It was from Tom Fanning, who went on to form his own Vale amateur entertainment company about 10 years later – The Happy-Go-Lucky Players - but who at this time was Secretary of the Dramatic Club. He was complaining about the public’s lack of support for the production. It was, he wrote, a financial failure and there was no money to donate to charity. However he said “members will persevere along the same lines next season, with the expectation that the indifference of the Vale of Leven public to high class plays will eventually be overcome”. The tone of the letter suggests a mixture of anger and concern.

The Dramatic Club did indeed persevere and in October of 1925 they put on their next show, a play called “The Professor’s Love Story”. This was a comedy in 3 acts by Sir J M Barrie, the Scottish playwright, who was of course the author of Peter Pan, and one of the most successful playwrights in the world in the early 20th century. If the Vale audience didn’t turn out for Barrie, then just who would they turn out for? This time the producer was RA Neil from Alexandria and the cast included Andrew Graham, Archibald Carmichael, James Mudie, John Simpson, John Aitken, Sam Snowden, Misses Helen Snowden, Helen McFarlane, Muriel McGregor, Rebecca Sharp, and Kitty Fraser. The ancillary arrangements were as  before – trams, booking etc, but the prices were a bit higher ranging from 1s for the back area to 5s for the Dress Circle and 15/- for a private box which held 6. The show was a great success and Mr Kippen delivered a vote of thanks to everyone involved, particularly those who came along.

before – trams, booking etc, but the prices were a bit higher ranging from 1s for the back area to 5s for the Dress Circle and 15/- for a private box which held 6. The show was a great success and Mr Kippen delivered a vote of thanks to everyone involved, particularly those who came along.

The Club’s production in January 1927 was a return of a show which had been performed at the Empire about 10 years previously by a touring company – “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, this time without the “Real Negroes”.

We have the accompanying poster including the cast list for this show, thanks to Jim Biddulph.

Click images to view larger versions.

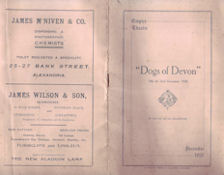

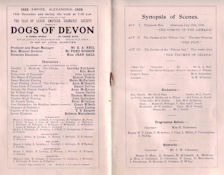

The December 1928 production by the Drama Club was in fact a comic opera "The Dogs of Devon"

Jean Henderson, whose mother Rebecca Malcolmson played Queen Elizabeth I, has provided a complete program for that production which contains not just the full cast list (which even allowing for a bit of doubling up here and there, had over 60 artists) but also the off-stage team of make-up, property master programme sellers and stewards.

The Orchestra has names that will still be recognised by many in the Vale to-day especially the Perellis who featured for many years in local dance bands and the Dowds.

A further bonus is the on-stage photographic record of the cast members, which not only gives a clear picture of the costumes but also of the scenery and the size of the stage. One of these photographs even made it to the pages of a Glasgow newspaper, probably The Bulletin.

The only person whom we can definitely identify in these photos is Queen Elizabeth who is played by Rebecca Malcolmson.

|

|

|

From the left, cast members onstage, The Dogs of Devon Visit Dumbartonshire and The Dogs and Good Queen Bess. Click images to view larger versions.

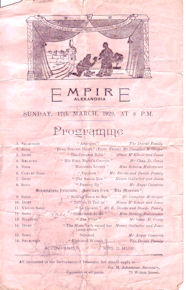

Music seems to have been just about as important to the Dramatic Society as acting was, although the music preferred by its members was perhaps more wide ranging than that usually performed by the Operatic Society. The program (left - click to enlarge) for a concert put on by the Society one Sunday night in March 1929 gives some indication of the members’ versatility.

Prominent amongst the performers were Mr Dowds and the Dowds family. The family included Andy, who went on to teach many people in the Vale to play a musical instrument, particularly the piano, and Bobby who was the one person who came up through the ranks of the Dramatic Society to go on to a very successful career in the theatre, and of whom more below.

A story from his brother Andy typifies the spirit in which the Dramatic Societies were performed by the members and received by the audience. In one of the Society’s productions the moon was hung in front of the roofs and chimneys!

The mistake was spotted by the audience as soon as the curtain opened and their laughter stopped the show for a minute or so. The laughter was a mystery to the actors on stage because they couldn’t see the offending moon hanging above their heads. Only the stage hands and manager were not amused.

The Vale of Leven Amateur Operatic Society

The Operatic Club had presented light operas from 1910 onwards when The Mikado launched them on the Vale public. Thanks again to Jean Henderson we have some photos from their shows. The Society’s early productions were not put on at the Empire, but all of their later ones were, until the Empire closed. After that the Society’s annual productions transferred to the Co-operative Halls. The Society’s first seven productions were Gilbert & Sullivan Operas.

This made perfect sense because these operas were not just very popular then as now, but they were also quite fresh having been written only a decade or so before the Society started to perform them. They are well within the singing and acting abilities of most participants in amateur operatics, which is one of the reasons why they remain firm favourites with operatic societies to this day.

When the Society decided to change from Gilbert & Sullivan they chose another composer who has remained a great favourite, Offenbach, and in 1922 performed his Grand Duchess of Gerolstein. The production in February 1927 was Lionel Monckton’s “Country Girl”. We have not only a poster for that production, but we also have photographs of many of the cast.

When the Society decided to change from Gilbert & Sullivan they chose another composer who has remained a great favourite, Offenbach, and in 1922 performed his Grand Duchess of Gerolstein. The production in February 1927 was Lionel Monckton’s “Country Girl”. We have not only a poster for that production, but we also have photographs of many of the cast.

The cast list for Country Girl illustrates the cross-over in membership between the two Societies – e.g. Cosmo Macbeth and Andrew Graham who perform in Country Girl were regular actors in the Dramatic Society productions. Andrew Graham took the lead in the Dramatic Club’s 1925 production of The Professor’s Love Story while Cosmo McBeth was in the Dogs of Devon 1928 with the Drama Club. Rebecca Malcolmson was another who was a member of both societies. Nor was the cross-over restricted to the players, Mr J Kippen was the President of the Dramatic Society and an Honorary Vice President of the Operatic Society.

This cross membership forced the players to make some choices because both societies put on a production in February – March each year, and it wasn’t possible for actors to be in both, mainly because of the rehearsals rather than the performance itself. Since the Dramatic Society usually presented a play in September – October time, if someone missed the first one, they had a good chance of appearing in the autumn production.

The following year, in February 1928, the Operatic Club’s offering was Merrie England which was another offering based in Elizabethan times and again it had been written by a very popular composer Edward German.

The following year, in February 1928, the Operatic Club’s offering was Merrie England which was another offering based in Elizabethan times and again it had been written by a very popular composer Edward German.

Click images to view larger versions.

First performed in 1902 it quickly became very popular with amateur clubs. Its peak year was probably 1952 when, spurred on by the Queen’s coronation, a truly astonishing 500 amateur societies performed it. It has fallen into obscurity since and so we are spared the delights of hearing such certain hits as “Dan Cupid Hath a Garden”.

In February 1931 the Society presented The Mikado in the Co-operative Hall, the first time for many years that they had not used the Vale Empire. This is the most positive evidence we have that the Empire closed sometime in 1930. The loss of the Empire did not mean the end of the Operatic Society. In March 1934 they performed the Yeoman of the Guard at the Co-operative Halls and after the final performance Mr A W Smith was presented with a medal for 25 years of service with the Society.

There are a couple of photographs which we have been unable to accurately identify.

(Click images to view larger versions.)

The costumes in the first of them suggest that it might have been from a performance of the Pirates of Penzance, but that’s just a guess. What is particularly impressive in this photo is the size of the cast (46 people) and how they and the scenery are comfortably accommodated on the stage.

The second shows an impressive trio of costumes being worn by members of the cast.

The Final Curtain

By March 1930 there were no adverts for nightly performances at the Empire of either films or variety. On 1st March 1930 there is the last advert which we can find for the Empire and that is for a Go-As-You-Please. After that there were no more adverts and it’s only thanks to a couple of short news reports in the Lennox that we know that the Empire was still open at that time.

On 12th April 1930 the Lennox reported on a professional boxing match which had taken place in the Vale Empire and which had attracted a good house, perhaps because Willie Quinn of Renton was on the card. Although boxing was popular in the area, the usual venue for it was the Northern Halls at the bottom of North Street, so boxing at the Empire was a rarity, another indication that the management was trying anything to keep the theatre open.

The absolutely last event we can find being held in the Empire was also in April 1930, shortly after the boxing match. No-one will be surprised that it was a display of Highland Dancing organised by Jessie Stewart.

By about this time the Vale of Leven branch of The National Unemployed Workers Movement was renting out the Empire’s workshop for their rooms. No doubt the rent helped a little, but by February 1931, they were complaining to the Council that the owners wouldn’t provide them with toilet facilities. In February too, the Operatic Society’s move to the Co-operative Halls is apparent proof that the Empire was closed as a theatre. The Valuation Roll for May 1931 still lists the building as being used as a Theatre, still owned by Trustees of the late James Boyd and still being tenanted by the Vale of Leven Premier Picture & Variety Company. However by this time there is no evidence of any theatrical activity.

By May 1932 it is officially described as “empty”, with no tenant or occupier. The theatre was therefore closed and completely unoccupied, although the NUWM still occupied the workshop as its branch rooms in 1932.

The Empire was demolished in late 1933 / early 1934. The site was acquired from the Boyd family by the Scottish Wholesale Co-operative Society’s Funeral Department. The SCWS was the overall organisation to which all Scottish Co-operatives, including the Vale Co-op belonged, but it was a completely separate organisation from the Vale Co-op. The SCWS Funeral Department already operated in the Vale but was looking for new premises. Within a year or so it had built a garage, workshop and mortuary on the old Empire site, and although it has replaced these mid-1930s buildings, it has been on the site ever since.

It is clear that in its last few years the Empire had been fighting an uphill battle, and it’s likely that the arrival of the talkies forced its management into a decision about converting the theatre to show talkies or closing up. It’s not so clear why they decided to close rather than convert, because many others who were in a similar position to the Empire made the choice to convert and survived – the Strand, Hall and Roxy all did so in the Vale and survived for another 30-40 years. The early 1930’s were a particularly hard time economically in the Vale, and one can only guess that the management company, the Vale of Leven Premier Picture & Variety Company, had lost its appetite for the fight.

The Empire was sadly missed by everyone who took part in performances there and by its Vale audiences; all of them had very fond memories of the Vale Empire. The performing clubs particularly regretted its loss when they had to make do with the lesser facilities on offer from the alternative halls, but that was the way of the world and they moved on, with the occasional regretful glance back at the “good old days” of the Vale Empire.

Postscript - Bobby Dowds, from the Vale Empire to the Glasgow Empire

The one person who cut their teeth at the Vale Empire and went on to be a major figure in the Scottish theatre was Bobby Dowds. As already mentioned, Bobby was a member of that accomplished Vale musical family, the Dowds. With his father and brothers Bobby appeared in a number of the Dramatic Society’s shows at the Empire in the late 1920’s and this experience obviously gave him a taste for the theatrical life. By the late 1930’s, Bobby was the musical director of theatres in Dundee, including working with Dundee Repertory Company, then as now, a leading training ground for young theatricals.

After the war Bobby had moved to Glasgow and by the 1950’s was the musical director and sometimes accompanist at the Glasgow Empire, one of the top two or three variety theatres in the UK. According to Frances Bruce in Scottish Showbusiness: Music Hall, Variety and Pantomime (2000) “Bobby Dowds, a long-serving musical director at various theatres including Glasgow Empire, was highly regarded for his musical skill, being able at short notice to provide full transcriptions for the instrumentalists in the orchestra from piano scores supplied by visiting headlining singers.”

These headlining singers included some of the biggest international stars of the day such as Guy Mitchell, The Deep River Boys, Frankie Vaughan, Sarah Vaughn, Billy Daniels, Larry Parks who had a couple of huge film hits playing Al Jolson, Lonnie Donegan who was the top of the bill when Des O’Connor took his famous dive, as described below, as well as more local talent such as Dickie Henderson and Andy Stewart and the White Heather Club.