Tullichewan Camp, Balloch 1942 – 1953

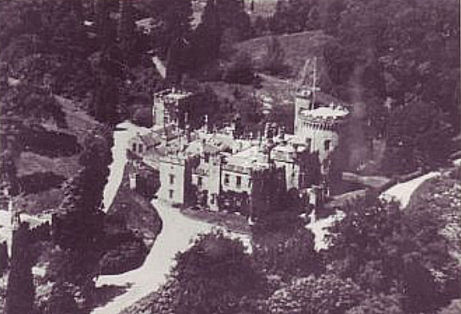

This is an image of Tullichewan Castle. The only part remaining is the stables building, which can be seen at the bottom left of the above image. The stables are clearly visible from the west side of the A82 just beyond the Roundabout above Balloch as you head towards Dumbarton. The Alexandria by-pass now runs through the site of the former castle, with most of it probably lying under the north-bound lane.

Introduction

Like a number of other estates and buildings in the Vale of Leven, Tullichewan Castle and some of its adjoining land was taken over by the government during the Second World War to assist the war effort. A camp was consisting of Nissen huts was built close to the orchard / walled garden, and the Castle was also used. Most of the smaller Nissen huts were used for accommodation, but other larger ones housed a drill hall, lecture rooms, stores and even a camp theatre. Accurate information about the camp is very difficult to come by from official records.

Fortunately there are still some eye-witnesses about, who can fill in the some of the gaps, while others have provided a written record of their time at the camp on the internet, Dennis Royal’s book Base Two useful provides accurate information about part of the Camp’s use, and we have first-hand contributions from some of its post-war residents, particularly Danny May. Phil Graham provided information about Body Lines Camp, while Malky Lobban from Australia and in his book “A Close Community” and Andy Miller from Canada provided memories about the Americans’ time at the Camp. Louise Yeoman of the BBC’s Radio Scotland’s Past Lives program has also managed to unearth some archive information about the WRENs use of the Camp and a number of recollections from former WRENs about their time at the Camp.

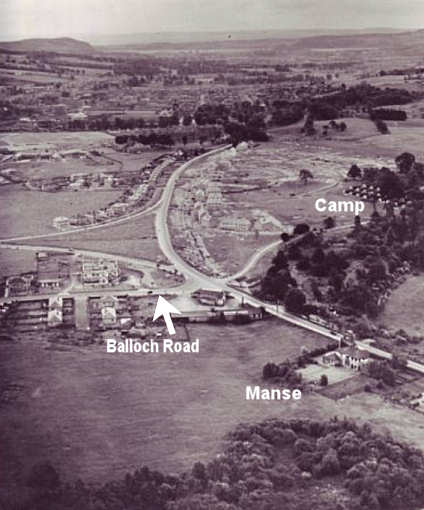

Indeed it is Louise’s interest which has prompted this more accurate re-write of the camp’s history. Finally, Graham Hopner of Dumbarton Library has made available a number of letters which he received over the years from formers WRENs and sailors or their relatives and friends. He also provided the aerial shots we have of the Castle and part of the Camp both of which were taken about 1946 / 7.

In summary, the Camp went through 4 distinct phases of use:

1 - Spring 1942 – June 1943. The Americans were in residence. The camp was built by the American civilians and their Irish colleagues who had started to lay the Finnart – Old Kilpatrick pipeline, in the spring of 1942. They were certainly its first occupants, being in residence from when the pipeline work started in May 1942 until it was completed in July 1943. At some stage, probably December 1943, they were joined by members of the 29th US Construction Battalion (the Sea Bees) who by April 1943 had taken on responsibility for the completion of the pipe-line (and the Finnart oil terminal) and stayed until the work finished about the end of June 1943.

2 - July 1943 – late 1944. The camp was a training base for the WRENs, many of whom went on to work on the most secret project of the war – the breaking of the German Enigma codes and the reading of Germany’s most closely guarded messages, based at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. We do not have a firm date for when the WRENs left Tullichewan, but it seems to have been before the end of 1944.

Up to this point Tullichewan Camp was called HMS Spartiate II by the Royal Navy whose property it was. The Secret Scotland website says that it was called Spartiate II from when it opened in 1942 until 1944.

3 - 10th March 1945 until 10th June 1945. It was renamed HMS Tullichewan and used as a holding base for Combined Operations. It was officially paid off in June 1945.

4 - 18th August 1946 – 1953. One Sunday in August 1946 local families, who could not find houses anywhere else, moved into the accommodation huts in the Camp, very much against the wishes of the authorities. In fact the camp was still guarded by the Navy at the time. They stayed until they were rehoused in the new council houses, which were built elsewhere in the Vale of Leven. The last of them had been rehoused by 1953 and the camp was demolished.

This is an aerial of the top of Balloch Road and southwards across Tullichewan, Levenvale and the rest of the Vale shows the camp on the mid right hand side. The castle is just out of the picture. This picture was taken about 1946 by the Ordnance Survey who did a more or less complete aerial survey of Scotland in 1946 - 47 as part of what was called the Mosaics Project. They used ex RAF Reconnaissance Spifires and Mosquitos and pilots and its quite a story in its own right.

1. The Camp’s Beginnings

The German victories in Western Europe in 1940 meant that the ports in the south of England were extremely vulnerable to naval and air attack. Liverpool and Glasgow became the major ports for handling the imports on which the UK depended, while the Royal Navy withdrew most of its larger ships from the southern ports and looked to the northwest for a new Atlantic base. Faslane was chosen and designated a new Military Port. By late 1940 5,000 Royal Engineers and Pioneer Corps men and about 200 ATS women were working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 52 weeks of the year to build Faslane Military Port 1. It officially opened in August 1942 and by then the Army and Navy well understood the challenge of that size of civil engineering project.

At about the same time as Faslane was started, the UK authorities had also decided to build a new deep water terminal somewhere on the Clyde, and in early 1942 they eventually decided on Finnart on Loch Long. It would be operated by the British Combined Petroleum Board, which managed the UK’s oil resources during the war and at this time the whole project was entirely a British matter.

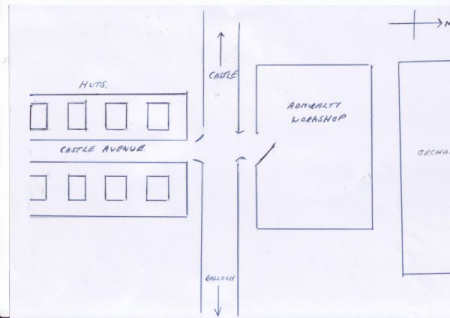

This is a simple plan of the camp drawn from memory by Danny May.

In the meantime, in March 1941 the US Congress approved the Lend-Lease Agreement which Roosevelt had agreed with Churchill to support the UK war-effort without actually joining in. A secret part of this deal was that the UK would provide the US with 4 bases actually in the UK (the others were mainly on the UK’s colonial islands in the Caribbean). It was kept secret, mainly so as not to further antagonise the Germans against the US, but it also meant that the British public didn’t know anything about it either and there was some surprise when American civilians started to turn up in numbers in the localities of the bases. The naval bases were at Londonderry (Base One because it was started first, being nearer the Atlantic Western Approaches and was the best available turn-round point for the the convoy escort ships) and Base Two, at Rosneath in the Gareloch. The other two were naval air-stations, one at Loch Ryan in south-west Scotland, and the other at Lough Erne in Northern Ireland.

After the sites had been selected, no time was wasted in making a start to building the bases. It was recognised that the building effort was probably beyond British resources at that time and the US Navy decided to use experienced US personnel. They chose 2 American companies to do the work, signing contracts in June 1941. As non-belligerents, the Americans were civilians and the cover name of Temporary Aviation Facilities (“TAF”) was given to the builders. Within a month or so 1,150 American builders were heading for Britain, starting at Londonderry, but soon spreading out to the other bases.

Local labour was also desperately needed too, of course, and given the need to maintain secrecy from the Germans, the remedy seems a little perverse. Because they were starting in Londonderry, the Americans recruited from Ireland, mainly from what was called “The Free State” at that time, in fact mainly from Donegal which was right on their doorstep. It seems perverse because The Free State was neutral and there was a German embassy in Dublin.

There were also German spies on the banks of Lough Foyle watching shipping and submarine movements in and out of Londonderry. In fact there were tens of thousands of Free Staters already working in the UK, to say nothing of the same numbers serving in the British armed forces, and Glasgow was pretty well regarded as the capital of Donegal at that time anyway. In the event, there were no security breaches. German Intelligence never found out about the bases before the US joined the war, and even after that they don’t seem to have been much interested in them – by then they were too pre-occupied with the war with Russia.

In July 1941 officers from the USN Civil Engineering Corps arrived in civilian clothes at Rosneath, followed a month later by about 325 American and 1,000 Irish building workers. They recruited about 250 local employees and set about building Base 2. The build lasted from August 1941 to May 1942.

Just as the build was coming to an end, the decisions had all been made about the deep-water oil terminal. It would be built at Finnart with a 25 mile pipeline to Old Kilpatrick via Glen Fruin, Loch Lomondside, the Vale of Leven, Dumbarton with a spur to Bowling, and on to Old Kilpatrick. At Old Kilpatrick there was not only an Admiralty jetty just south of the Erskine ferry slipway, but also a connection to the Grangemouth oil refinery via a pipeline already laid along the Forth & Clyde Canal towpath. Another 7 mile pipeline would run from Finnart to Rosneath Base 2’s tank farms.

By the time contracts were being allocated for this whole project in the spring of 1942, TAF’s work was running down at Base 2, so they had plenty of spare resources already at hand. Perhaps more importantly, by then the UK authorities were mightily impressed with the speed and quality of TAF’s work in building the Secret Bases. It was no surprise, therefore, that TAF was awarded the contract to build Finnart and lay the pipelines. Work started on both in May 1942.

According to the Lennox Herald, TAF built not only the Tullichewan camp but also another one at Bowling to house the US civilian and Irish workers, who were going to lay the pipeline. This was done around May 1942. Whether or not the camp was called Spartiate II at that stage is unknown, although most sources say that it was.

The Americans made a considerable impact on the people of the Vale and have lived long in the Vale’s collective memory. Malky Lobban’s book “A Close Community” paints a vivid picture from his then-young memory, while Andy Miller writing to this web-site from Canada paints a similar picture. Partly it was the visual impact: they wore high-heeled boots, Levi jeans and Stetsons and they all seemed to smoke cigars. Partly it was their material wealth – flash cigarettes like Camel, Lucky Strike, Philip Morris, chocolates like Hershey Bars, white butter which no one had seen before. And partly it was that they were friendly by nature and people got on well with them.

But no good deed goes unpunished and their attempt to give local children a happy Christmas Party in 1942 in Tullichewan Castle (which they used as their mess hall) turned into a wee bit of a disaster when too many children turned up and many were locked out. Even after all these years, Malky Lobban, one of the disappointed children, still feels the pain.

Their material wealth gave them the means to engage in friendly bartering in all sorts of quite predictable ways. An amusing consequence, now at least, on their bartering was the regular appearance at Dumbarton Sheriff Court of girls who had been charged with “trespassing in huts in Tullichewan encampment”. In one case from August 1942 the Procurator Fiscal said that no security breach had taken place and he’d leave it to people’s imagination as to why the girls were there. In another case, the stuffy Sheriff complained that such cases were becoming too common – perhaps he was bitter that no young girls were breaking into his bedroom. Nowhere did it say who the girls were visiting in the camp, presumably omitted for security reasons.

Laying the pipeline was difficult work, partly because of the boggy ground conditions for much of the way, partly because of what the Americans thought of as non-stop rain. But considering it was nearly 70 years ago, good progress was made, averaging about 2 miles per month.

In November 1942, 740 Sea Bees of 29th Sea Bees (US Navy Construction Battalions) arrived at Rosneath and they were joined by another 300 in December making up 1,140 in all by the end of 1942. Some of these Sea Bees were drafted into the pipeline work and took up residence at Tullichewan. TAF’s contract ended in March 1943, and by April 1943 the Sea Bees assumed complete responsibility for the final phase of the Finnart and pipeline work. In July 1943 both the Finnart Oil Terminal and the pipeline were handed over to the British Combined Petroleum Board. Shortly before then, probably in June 1943, having no further use for the Camp, the American and Irish civilians and the Sea Bees vacated it.

2. The WRENs at Tullichewan.

It didn’t lie vacant for more than a few weeks, because we now know from a former WREN, who was in the first group of WRENs into Tullichewan Camp soon after the pipeline workers had left, that the WRENs moved in in July 1943. They found the place a real mess – dirty / untidy, in need of repair, hardly a working toilet anywhere: in short pretty well what you might expect after a group of hard working and hard living men had just left. For the whole period when the WRENs were using the Camp, it was known as Spartiate II. Spartiate I was headquartered in the St Enoch Hotel in Glasgow with out-stations at Bowling and Greenock. It was a fully operational base which was in charge of river security on the Clyde, deploying cabin cruisers – many of which had been built by Silver’s yard at Rosneath - armed with machine guns to carry out patrols. There appears to have been no connection between Spartiate I and Spartiate II, other than the name. The security patrols on Loch Lomond did not make use of Tullichewan.

Tullichewan Castle

The camp was in two separate locations: Tullichewan Castle and about 300 yards down the northern driveway in a north-easterly direction, a group of Nissen huts in which the trainees and their NCOs lived. There was also a drill hall, a mess, a fo’castle, galley, and various offices and lecture rooms. No mention is made in any WREN accounts of a camp theatre, but many Vale people well remember dances, shows and concerts being held in what they took to be the camp theatre complete with stage, when the Navy was in possession. It’s possible that the drill hall building was put to that use after the Navy took over in 1945, which is from when most Vale recollections of a theatre date.

It almost goes without saying that from the moment that the WRENs moved into Tullichewan Camp, the officers took themselves off to live in Tullichewan Castle, where they stayed for the duration, while the other ranks were given the job of clearing up their living quarters in the Nissen huts to make them habitable.

Spartiate II for all the time it was used by the WRENs was exclusively a training camp where initial basic training was carried out. Initially it was used to train inductees from the North of England and Scotland, while those from the Midlands south were trained at Mill Hill in London, which was the headquarters for the WRENs. However, for a time bombing or more likely the V1 / V2 attacks, made Mill Hill unsafe and all WREN training took place at Tullichewan. It is reckoned that as many as 650 WRENs were accommodated there at the peak time, which must have made it very crowded.

Accounts vary about how long the introductory basic training courses lasted – some former WRENs reckon they were there for 2 weeks, while others say 3 or 4 weeks. In any event it was a short time, although it certainly did not seem short to those who went through it. It is likely that it was an intentionally rough and pretty brutal few weeks and the attitude was “if you can survive this you’ll survive anything the WRENs can throw at you”. Mostly the camp was handling young “ladies” from middle class backgrounds, many of whom had signed up on the very day that they were old enough to do so, on their 18th birthday. For many, this was their first time away from home. Anything short of home comforts would probably have been a shock to the system, and Tullichewan was certainly that all right.

The typical travel arrangements were that the young ladies would arrive by train from Glasgow at Balloch station and walk up Balloch Road and across Luss Road to arrive, suitcase in hand, at the guard-room. There they would be assigned to a hut – there were 8 trainees to a hut, double bunked - and the training would start the next day. The daily routine was to be wakened at 4.30 by a tough old CPO who ran a stick along the corrugated iron sides of the huts shouting “Wakey, Wakey”.

From 5 to 7 am they did daily duties such as scrubbing floors, cleaning the latrines and emptying the bins. Since most of them were from well off homes and had maids who did this sort of thing, all of this was a completely new experience, which still seems quite foreign to some of them more than 65 years later. However, they mostly seem to have handled it pretty well, in the spirit of the times. After breakfast at 7.30, there began a daily programme of drill and lectures.

Some describe the conditions and the training as “horrendous” while others say it wasn’t too bad. Just how critical they are of the interior of the huts seems to be influenced by whether they were there in the winter when they were freezing – only a single stove in the middle of a hut which had 8 bunks in 4 double tiers. In the winter the stove always seemed to go out and the supplying fuel seemed to be the duty of the only soldier who is mentioned in any of the recollections, not fondly remembered either, it has to be said. One former WREN describes him disappearing of an evening “down to a pub in Balloch”.

That has a ring of truth to it. One talks of walking to Alexandria and Jamestown and mentions going to the YMCA. She doesn’t actually say so, but the YMCA in Bridge Street housed a Forces Canteen and she may well have been heading for that. Most say after all these years that they have fond memories of their stay there, mostly based on shared experiences and making new friendships rather than on their surroundings outside the camp.

It is very striking that there is hardly any collective memory in the Vale of the WRENs being at Tullichewan. And yet they were the group that was at Tullichewan for the longest time – 18 months from July 1943 until the end of 1944. They were also there in the greatest numbers – at any one time probably 200 – 300 and as many as 650 at peak times. But any one of them was only there for a short time, too short a time to make contact and friendships with the locals. In any event, they were probably too tired of an evening to want to go out much. Perhaps conclusively, there was a very marked shortage of that group of people who would have taken a great interest in 200-300 young women on their doorstep – most of the young men were away at war.

Historically, the greatest interest in the WRENs probably lies in what they did after their basic training. Many went off to work on Britain’s greatest secret of WW2, one which was kept from the public until the 1970’s – the decryption and reading of German military signals – army, air-force and navy - by the Enigma code breakers based at Bletchley Park. At Bletchley and its outstations, much of the essential administration and electrical equipment operational work was done by WRENs – wiring the bombes or computers which actually broke the coded messages, listening to and transcribing the German radio messages, loading paper tapes, transporting tapes between the secret bases etc.

In all there were about 1,500 WRENs involved in this most secret and arduous work and many of them had done their basic WREN training at Tullichewan. Indeed Louise Yeoman of the BCC’s Real Lives programme has discovered that one of the former WRENs who worked on ENIGMA and who is currently a guide at the Bletchley Park Museum (February 2010), did her initial training at Tullichewan.

There are a number of descriptions of their experiences at Tullichewan and Bletchley written by former WRENs on the internet, particularly at the BBC’s WW2 People’s War site. These include Marian Durran’s Story at www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/43/a2478143.shtml

... and another by a couple of former WRENs at the same site. Since some accounts have mis-spelled Tullichewan (Tulliechewan is the most common variant) try a few spellings if you search the net.

In the early 1990’s a former WREN, Mrs HEL Moore who by then was living near Darlington, wrote to tell Graham Hopner that she was writing a history of the WRENs at Tullichewan Camp and that she already had written 18,000 words and collected a number of photographs. Unfortunately that work seems to have come to nothing.

By the end of 1944, the WRENs had stopped using Tullichewan Castle and Camp and it lay empty for a time.

3. HMS Tullichewan.

On 10th March 1945, when it was clear that the war in Europe must end soon, the Navy recommissioned the camp as HMS Tullichewan. They intended to use it as a holding depot for Combined Operations, a unit which had had a strong presence in western Scotland from the early days of the war. Combined Ops had a major base at Inverary and had moved into another on the Gareloch. Unless there was a plan to send Combined Ops to the Far East to help in defeating Japan, a plan which has not so far seen the light of day, it’s a bit of a mystery why the Navy should have gone to the bother of commissioning HMS Tullichewan.

However, people do remember the Navy at Tullichewan, and Graham Hopner has one letter on file from a friend of a sailor who served at Tullichewan in 1945. The most common memory is, as mentioned above, of attending social functions in what is usually described as the camp theatre after the war. The only other record of note about the Navy being at Tullichewan camp at this time is that HMS Tullichewan entered a football team in the last Holidays at Home competition in the summer of 1945, in which they were beaten 3-0 in the final by a Babcock & Wilcox works team.

The Navy “paid off” HMS Tullichewan on 10th June 1946, but didn’t vacate it entirely. As we shall see, they left a guard at the front gate. It seems that the Admiralty had plans for the Castle and for some of the buildings in the Camp. It is said that they were going to use the Castle as a hostel for key workers that they were going to bring over from the RNTF at Greenock to work at RNTF Alexandria. That’s always possible, but the Admiralty also announced in the summer of 1946 that they were going to expand employment at both factories by very similar numbers, and that they would employ the same number of people at both places, so you have to wonder why they would be sending anyone from Greenock at that time. They also retained one of the buildings as a store / workshop and some version of that building survived in Admiralty use for many years.

4. The People’s Place.

By the end of the war there was a desperate shortage of housing in the Vale, as there was in much of the rest of Britain. An indication of this was that even after the war ended, there were still 6 families living in the shanty town or encampment of home-made huts at Lesser Millburn. Although this was well down from the 150 people who had been there through the previous winter of 1944-45 it was an affront that people should still be living in the Vale in these conditions in the middle of the 20th century.

The encampment, which had existed since the hungry 30’s but has been almost completely written out of the Vale memory, was a good indicator of the level of poverty and social deprivation between the wars. To help ease the problem, the Council had already taken over the hostels on the south side of the Carrochan burn at Jamestown and put families in there. It had been looking at using the small Ballaghan Camp which had housed Italian POWs, but thought that it was unsuitable at that time.

However, by 1946 most of the conscripted soldiers had been demobbed and had come home. In the Vale, like elsewhere, many came home to find no accommodation for them and their families. In the meantime, many if not most of the camps built for war-time needs had been emptied of their military or POW inhabitants and were lying empty. The remedy seemed obvious all over Britain, particularly to ex-servicemen with families; everyone that is except central government.

By the spring of 1946 ordinary people all over Britain were taking over the empty camps, almost always against the express wishes of the authorities, whose official approach was that these camps were “vacant but not spare.” They compounded this piece of idiocy by saying that some of them would be needed in the future to house Polish soldiers, who weren’t going back to Poland, and their families. So, British ex-servicemen, newly returned from serving King and Country were to be denied housing for their families and instead it was going to be handed over to the Poles, or even more likely, was going to lie empty indefinitely. As the letter quoted below from the camp residents committee amply shows, people were not going to accept that; their attitude is best summed up as “that’ll be right”.

There were three more or less empty camps locally: at Tullichewan (which still had a Royal Navy presence), Bodylines at Dillichip, Bonhill (which had housed Italian PoWs but which was empty by August 1945), and at Kilmalid / Gooseholm just inside the Dumbarton burgh boundary (which by the end of the war housed RASC stores). People power swung into action and all three were occupied in August 1946, two on Sunday 18th August, the other a very short time later.

The move started at Bodylines (or as all official references call it, Body Lines) early in the day that Sunday, when 22 ex-servicemen and their families moved unopposed into the camp and quickly made themselves at home. “At home” is a wee bit of an exaggeration, because that day there were 4 families to a hut and each family was separated by having a blanket strung across the interior of the hut to delineate each family’s living space. These arrangements, which are gob-smacking now, were a considerable improvement on what they were moving from. The interiors were soon improved a bit and 1 or 2 families per hut separated by fixed wooden partitions became the norm. By Sunday afternoon they were all in and settled. This was the quiet before the storm which broke about their heads at midnight.

Across the valley, the storm was very much up front as a crowd of people tried to force their way into Tullichewan Camp in the early afternoon. The Camp was still guarded by the Navy and this first attempt to enter the camp was repulsed. The remedy was really quite simple – get a bigger crowd, which is what the families did. In the evening, a much bigger crowd simply overwhelmed the guards, who were powerless to repel them. By midnight 60 families had claimed accommodation in the accommodation huts and many did not leave again for 7 years. People power had won, and by the end of the week there were 84 families living in the huts at Tullichewan.

Over at the Bodylines Camp, which had been entered without any opposition whatsoever, midnight saw things turn a bit nasty for a while. At midnight in the pitch dark a lorry load of 20 armed Polish soldiers turned up to occupy the camp. Why did they arrive a few hours after it had been occupied, when it had been lying empty for so long? Almost certainly the answer is sheer coincidence because it seems that they did not expect to find anyone in residence and that this surprise, plus the darkness and language problems caused a confrontation between the soldiers and the camp occupiers.

It could have got out of hand were it not for the timely arrival of the Vale police who were quickly on the scene and calmed things down. But those present thought that it had been touch and go for a time. The Poles sought orders from above and were told to return whence they had come – which was a camp at Bellahouston in Glasgow. By early morning on Monday 19th August the families were in undisputed possession of Bodylines, and they too stayed there until the early 1950’s. There were about 30 families at Bodylines, which made it much smaller than Tullichewan.

Questions were inevitably asked about why a lorry load of foreign soldiers were driving about Scotland, armed, a year after the war ended. They were never answered, but it was quietly accepted that that was just a cock-up, which was never repeated, at least to the public’s knowledge.

At Tullichewan, the Navy gave in gracefully, withdrawing its guard to the small area of the Camp of which it was obviously making use, and this was never at any time an issue. The Castle, empty and boarded up, was also left untouched after the Admiralty said that it did intend to use it. Although there are some Internet and published references to workers at the Torpedo Factory staying there after the war, so far we have found no proof of this. In any event, a light touch by the Navy and a quiet word all round seem have settled the matter. The Navy had what it really needed and 84 families had a roof over their heads.

Central government, which since July the previous year had been Clement Attlee’s Labour government, was horrified, as governments always are when the people in whose name they claim to be acting confound them. They labelled the people who had taken over the camps “squatters” and condemned their actions. The Health Department of the Scottish Office even went so far as to express the hope that they would move out “after the winter” and return to re-occupy the homes which they had just left. Even the Lennox Herald, which usually could be counted on to spout the establishment view in any situation, could see the flaw in that particular piece of nonsense – the people had no homes to return to, which is why they were in the camps in the first place.

The same Department had already said that the huts were quite unsuitable to spend a winter in anyway, so clear thinking was not their strong point. Again the Lennox Herald was sympathetic to the Tullichewan residents, saying that Tullichewan had been built by the Americans and was the most comfortable of the three camps, but any number of WRENs would testify that this was a very relative term.

The position of the Lennox Herald and of people generally who recognised the very real need was that this was a less than perfect, but at least practical, short term solution. That view was in sharp contrast to officialdom. Central government knew that it did not have any short term answer but instead of admitting that and publicly endorsing the people’s action, it condemned it. It fell back on a legal position, which it could have immediately changed had it been so minded. This had practical consequences both for the local authorities involved – Dunbarton County Council and Vale of Leven District Council – and for the families, and a Labour government might have been expected to know better. By its dog-in-the manger attitude it denied legality to and created long-term uncertainty for people who were just trying to find a place to live and bring up their families. Hardly “homes fit for heroes” a la First World War, but infinitely better than nothing.

The position of the families living in the Camps was set out clearly and unequivocally in a letter which appeared in the Lennox Herald, in pride of place at the top of the front page, on September 7th 1946, two weeks after the camps were occupied. It comes from the Secretary and Chairman of a committee set up by camp residents. The Lennox (which emerged from all of this with great credit) published the letter in full, and it’s worth also quoting the major part of it in as it appeared.

“The position created through the action of the authorities to provide modern homes with up-to-date furniture for foreign wives and families of foreign soldiers while condemning our own people to years of overcrowding in rat and vermin infested slums is the chief reason for the action which has been taken by our members.

The local authorities should use whatever powers they have to requisition huts, mansions and all available unoccupied dwellings and repair and reconstruct them.

There are those who say that squatters should now be placed at the back of the Council’s housing list. We seek no advantage, but expect our rights and should not be penalised for having the guts to do something for themselves instead of waiting for some council to give them a home.

Two families are sharing a hut with no partition and in most camps conditions are primitive. There is bad lighting, no cooking facilities, little or no heating, rats and smoking chimneys. We are clearly not well housed.”

The letter sets out the position of residents of the local camps quite clearly. It also touches on something which was being said at the time – that they were queue jumping on the Council’s Housing Waiting List. The major problem with that point of view in 1946 was that while there was a huge Waiting List, there weren’t any houses to give to people anyway, so it was impossible to jump the Waiting List. However, that was a view which some civil servants and politicians tried to feed the public as an alternative to doing anything constructive, and it did worry camp residents.

Some residents felt at the time that there was also a bit of a stigma to living at the camp, that they were termed a “squatter” and looked down on, but that’s not a Vale collective memory. At the time many people thought of the residents as having no alternative, and of doing absolutely the right thing. “More power to their elbow” was a common view. That most were ex-servicemen ensured that the public at large were on their side. Certainly to-day the view of almost everyone who remembers these times is “quite right too”.

The government’s refusal to recognise the reality of the situation was a problem for a couple of years. Strictly speaking it was an insurmountable legal obstacle for the local councils, particularly the officials. They were bound to adhere to what central government said was the legal situation. They had no duty to provide the usual council services to the Camps – in fact they might be breaking the law if they did so, was their public stance. No doubt, some officials did regard the residents’ behaviour as unjustifiable and were in tune with central government, but most thought otherwise, while saying nothing. They knew that the sanitary and cleansing, health and education, lighting and public safety and all the other council services would have to be provided, even if no one admitted as much. In the short term however, they had to pretend that the camp did not exist and the people did not exist. The Camps did not appear on the local Valuation Rolls, which were the basis of the Council’s income from the rates and a statement of all the property in the area, until 1948.

The councillors on the other hand, were a different kettle of fish. There were still people like Hugh McIntyre and Hugh Craig, Hector McCulloch and George Halkett, to say nothing of Dan O’Hare, on the council, who could be guaranteed to support the residents whether they were there legally or not. They had been finding ways round strict legal positions for years. A behind-the scenes deal was worked out which soon became as sensible a compromise as it was possible to have at that time. No explicit council tenants rights were given to the camp residents, but no attempt would be made to evict them. All the usual services were provided on one pretext or another, which kept the officials well clear of any accusations of illegal actions on their part. However, it is 1948 before there is visible acceptance by the Health Department of the Scottish Office that they were now the owners of the Camp. They devolved the housing management of the Camp to Dumbarton County Council which gave out tenancies to 85 Hut dwellers. They were at last council tenants and their existence and status was recognised.

This was very important because it meant that they were on the Council Housing Waiting List and were building up a history of tenancy with the Council. Even 3 or 4 years later when new houses were becoming available in the new housing estates at Dalmonach, Haldane and Tullichewan itself many residents had a real concern that they wouldn’t get a new house because they had moved into the camp and the council might deem them unsuitable tenants. That did not happen. The Council did send out its housing caretakers to make sure that people were looking after their Huts properly, before they were allocated a new house. This was Council standard practice for any potential tenants of a new council house at the time, but it seemed to many of the camp residents a further threat (which it was not) since it was impossible to keep these former military huts to the same standard as a normal house. They needn’t have worried because the council was as keen to move them to new houses as they were to go.

As soon as people moved in they began to organise themselves into a community.

The improvements carried out by the residents to make the camp more habitable also had an element of correcting what they saw as the perception of at least part of the public. The main lane in the Camp was called Castle Avenue and although the Council never recognised these names, everyone else did, such as the newspapers in their reports, postmen and delivery men. Gardens appeared around the huts and naturally enough people did what they could to make them more comfortable and warm – by no means easy. To begin with, the residents had to carry out all these tasks themselves, but after the Council gave out tenancies in 1948 the Council accepted its responsibilities as the landlord and life became a bit easier for the families.

However, no one was sad to exchange a hut for a Council house which, after all, was what they had wanted in the first place.

The Huts were empty by late 1953 – they had been pretty steadily emptying for about 2 years before that – and were demolished soon after. They stood for only 11 years, but these years had been pretty eventful and a lot of living had been done in them.

The Castle, which no one had moved into in 1945 or later, and was still the property of the Scott Anderson family, was blown up in 1954, with just part of the stables surviving beside the A82. These are the buildings in the extreme left of the accompanying photograph of the Castle. The Alexandria by-pass (A82) runs through what was the main part of the Castle.

Of the other camp buildings which the Navy retained in 1946, one is worth a mention. The Workshop / Stores, which stood close to the walled garden / orchard at the north end of the camp was still in use by the Admiralty until about the time that the Torpedo Factory closed in the late 1960’s, or maybe even a little later. It was upgraded and extended over these 25 or so years and only seems to have been demolished with the building of the link road up to the Alexandria by-pass at the Stoneymollan Roundabout in the early 1970’s. Its site is under the A811 road.