Churches and Schools in the Vale of Leven

This page will focus on the churches and schools in the Vale of Leven. The content below is related to the churches. Schools will be added at a later date.

The Roots of Alexandria St Andrews Parish Church

Note: This is the second edition of this article and was produced because within a short time of the publication of the first version a significant amount of new material was sent to the web-site to add to what we already had. Contributors to the article as it now stands include:

- Morag Bain who provided the images of the architects plan for Bank Street Church

- Fiona Jamieson who provided colour photographs of the Bridge Street Church and a copy of Dr Jeffrey Scott’s brief history of the Church

- Graham Lappin who contributed both the text about the Chartist Church and photographs of Bridge Street and North Street Churches

- Billy Scobie who helped place the churches within the history of Bonhill Parish.

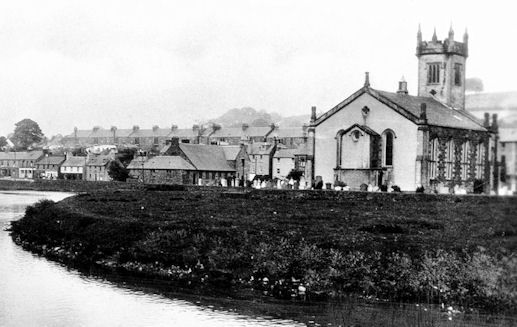

Bonhill Parish

Bonhill Parish is the medieval ecclesiastical and administrative entity which covers the northern part of the Vale of Leven from Poachy Burn at Millburn on the west bank of the Leven, and from about the Lions Gates on the east. Bonhill Parish Church has in some form or another existed close to where it still is for probably 700 years or more.

Bonhill Parish is the medieval ecclesiastical and administrative entity which covers the northern part of the Vale of Leven from Poachy Burn at Millburn on the west bank of the Leven, and from about the Lions Gates on the east. Bonhill Parish Church has in some form or another existed close to where it still is for probably 700 years or more.

It is a constant around which much change has taken place in church affairs in the area in the past 200 years. The present Alexandria Parish Church building and congregation on Lomond Road is the perfect example of these changes

Alexandria Parish Church is the product of the schisms, moves and amalgamations which characterise much of the history of the Church of Scotland in the last 200 years or so. Many of these happenings have been lost in the mists of time and that is quite understandable. What is perhaps more surprising is that much of the story which lies comfortably within living memory has also been forgotten. The church is actually in Balloch and there is now no CoS church in Alexandria, where from the 1930’s to the 1960’s there were three. That raises many questions, most are easy to answer but one at least is a little more difficult. The easy questions all fall within the broad categories of “why and when did this happen?” The much more difficult questions is “why were such fine buildings destroyed?” We’ll tackle the easy ones here; you can ponder the harder one at your leisure.

The present Parish congregation is an amalgamation not only of these three congregations, but also of a fourth, which lay across the River Leven in Bonhill. The main reason for the drawing together of these congregations at different times over a 30 year period was, of course, the decline in numbers in the various congregations, and the main reason for that were the changing habits in society. However, the eventual location of the united congregations had more to do with a general population drift from the centre of Alexandria and also potential pressure from town centre redevelopment – all common enough elements across Scotland.

What was also common all over Scotland by the late 20th century was the very considerable over-supply of large church buildings which housed small and shrinking congregations. Many of them stood like rocks on a beach from which the tide has ebbed a few hours before, which, in the sense that people had moved from city and town centres to the suburbs and new housing estates, was exactly what had happened. In Scotland there had been, since the Reformation in the mid 16th century, a very strong tradition of near universal Church membership and participation, so most towns and villages had church buildings which were large enough to accommodate most of the local population. This was a population which was steadily increasing throughout the 19th century and as it increased extensions were added to churches to accommodate them, which was a common feature in Vale churches until into the first decade of the 20th century.

This more than adequate supply of church accommodation was greatly added to by the various factions which emerged from the latter half of the 18th century onwards, because of discontent with the Church of Scotland. There were actually two phases of this discontent – an 18th century “Secessionist” or “Relief” movement which was largely rural based, and the 19th century one which culminated in the Disruption of 1843. Both were to manifest themselves in the Vale.

The 18th century discontent had some doctrinal basis. Today, it is perhaps most present in public awareness through Robert Burns’ work, particularly Holy Willie’s Prayer. Some of the terms it generated are also worth a mention – “Auld Lichties” and “New Lichties”, and “Burgher” churches which seem only too modern for the good of anyone’s health never mind their spiritual well being. The first “Relief” congregation in the area was at Kilmaronock where in 1770 the people rejected a minister being foisted on them by the local landowner who was also the feu superior. This fitted in well with the mood of the times and people from the Vale walked to Kilmaronock to attend Relief services. Sometimes the Relief minister came down to preach at the Parish Schoolroom, which in those days was at Jamestown, just north of where the school is now. In 1786 a Secessionist church was built in Renton by a group adhering to the Associate Burghers. It later was to become the Levenside Church and the building survived until the building of Hillfoot in the 1920’s, although by then it hadn’t been a Church for many years. People from all over the Vale also walked to attend that church.

One very visible difference between the Relief / Secessionist churches and the later post-Disruption churches, is that the Relief / Secessionist churches were simple, almost spartan buildings in comparison with most Free and UP Churches which came later after the Disruption of 1843. They were typically square, without steeples or external ornamentation – an excellent example survives in the Baptist Church in Bridge Street, which of course was built originally by a Relief congregation. This partly reflected doctrinal belief in simplicity, but the fact that the first congregations were rural and very much poorer than their later mainly urban counterparts also dictated the design of the buildings.

The discontent which had been rumbling on for over 70 years erupted in the Church of Scotland Disruption of 1843, and although a doctrinal gloss was put on the Disruption, unlike its 18th century predecessors, its roots were more church political or church economic than doctrinal. In essence, the emerging urban middle classes wanted to be able to choose their own minister rather than it being in the gift of a local laird (as it still is in practice in many rural parishes of the Church of England). So although the “Wee Frees” and their like of to-day are cast as fringe groups - both geographically and doctrinally - of religious conservatives, their origins were almost exactly the opposite and that had great implications for church-building. The Disruption was part of a larger movement for change in society at large – the 1832 Reform Act had started that process off, and by the late 1830’s and early 1840’s the Chartist movement, which was strong in the Vale, had taken up the campaign. But change was not coming fast enough for many, particularly the rich and articulate middle class. In Scotland they had another issue on which to press for reform, this time within an institution which they believed they could dominate – the Church. They were right.

The dissenters of the Victorian middle classes were getting wealthier by the year, and one very striking fact about the various factions which formed in Scotland after 1843 was that they were almost all well funded. As a result, they were able to embark on grandiose, in many senses of the word, church-building programmes when they split from the Church of Scotland. In 1843-44 the largest of the break-away Churches, the Free Church, built about 470 new churches, a number which had grown to 700 by 1847 – almost all with manses. The faction which eventually became the United Presbyterian Church (arguably the “sensible” wing of 19th century Scottish Presbyterianism) didn’t build anything like that number, but the quality of the churches which it did build was outstanding. The UP Church was helped, of course, by the fact that Scotland’s greatest 19th century architect, Alexander “Greek” Thompson, was a member. In Glasgow, for instance, virtually all of the finest Victorian Churches belonged to the Free or United Presbyterian congregations. Alexander Thompson was the architect on 3 of them, though not of possibly the finest, Wellington Church on University Avenue.

This is not all just some sort of vaguely interesting but irrelevant or incidental information, because what happened in Alexandria and the Vale generally conformed to the picture in the rest of Scotland which has just been described. By the end of the 1840’s, the congregations in the Vale which had left the established church had built church buildings with approximately 3 times the capacity of the Church of Scotland buildings. In the Vale, as in many other parts of Scotland, the established church had lost the argument and the majority of its adherents by the 1840’s. It is reckoned that the established church lost about 60% of its members during the Disruption, and that these leavers went directly to either the Free or UP Churches. The new congregations who departed were quick to re-house themselves in new church buildings.

Four of the dissenting churches which were built in the Vale were of outstanding quality and architectural interest - Millburn at Renton, which is the only one of which anything survives, Bonhill South, Bank Street and Bridge Street Churches. With the exception of Millburn, they were all allowed to pass away with insufficient effort to think of how they could be helped to survive as buildings, albeit not church buildings. Three of them were, of course, “ancestors” of the present Alexandria Parish Church. Bank Street or Alexandria North was the parent while the other two, Bonhill North and Bridge Street being, with Alexandria Parish, more in the way of aunts and uncles. The others all have their own points of interest, too. The four ancestral churches of the existing Parish congregation were, in the order in which they formed as congregations

Bonhill North Church, better known as “Mount Zion”.

This was the first of the four churches to be built. It belonged to the Relief grouping which had previously been served by the Kilmaronock congregation, but by the 1830’s was clearly large enough and wealthy enough in Bonhill to build a church for itself. When it opened on 27th February 1831 as a Relief church, its members were spared the long walk to Kilmaronock or the ferry crossing and walk to Renton. It was a classic Relief building, square and simple, sitting on the crest of a hill overlooking what was then the front gate to Dalmonach Works, hence its early name of “The Hill Church”.

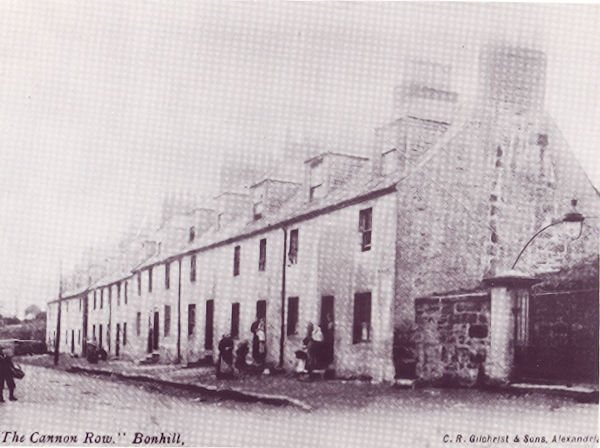

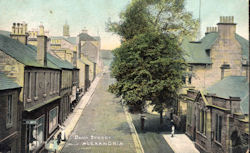

When it was built it stood completely on its own, well north of any other houses, shops etc and beyond the northern edge of the village. This may well have been intentional on the part of the local land-owner to place any but the church of the Establishment well away from the local population, and any existing church. It was not on its own for very long, because in the 1830’s a row of houses was built on the Jamestown Road right next to the entrance to the driveway leading up to the Church. This was initially called Church Row, but was later to become much more famous as the Canon Row, perhaps not the most salubrious address in the Vale, but still good enough to be the birth-place of the legendary Dan O’Hare. You can see just how close the Canon Row was to the Mount Zion driveway gate in the accompanying photograph. You can also see that the gates of the driveway are firmly closed.

The Canon Row and the driveway up to Mount Zion Church

A little more than 10 years after its opening there was a schism within this dissenting congregation. It was caused by a visit to the Vale by the Chartist agitator Feargus O’Connor that occurred in October 1841. The minister of Mount Zion, Rev Swan, had a fairly liberal attitude to permitting the use of the buildings by local organisations, but was not present when the application for use by the Chartists was made and granted by one of the deacons. He was horrified it would be used for political agitation and the resulting antagonism eventually led to a split, with the departing members setting up a separate congregation in Bridge Street, of which more below.

The Mount Zion congregation changed its adherence a number of times, mainly because the churches to which it belonged merged with others. At different times it was United Presbyterian, United Free but after the 1929 re-unification of the church, it elected to become a Church of Scotland Church as Bonhill North. After WW2 the Dalmonach housing estate was built at the back of the Church and it saw an influx of new members. Also after the war, it had the distinction of having a German refugee as its minister for a time. The Rev Rudolf Erlich had fled Hitler’s Germany and had become an ordained minister in the Church of Scotland. He left Bonhill about 1953 to become minister of a church in Leith, and his successor was Rev William McFarlane.

Rev McFarlane became a dominant church figure in the Vale in the second half of the 20th century and built up a very loyal following in his congregations. He was actually the minister of the single charge of Bonhill North for only 5 years or so, because when Rev Colin Munro retired from Alexandria Old Parish Church, as it was officially called then, in March 1958, it was decided to link the churches of Bonhill North and Alexandria Old Parish Church. A service of inaugurating and linking of the two churches, and of inducting Rev McFarlane to the Parish Church was held in the Parish Church on Thursday 26th June 1958. From that date forward Rev McFarlane was minister of these two quite separate congregations, worshipping in their two separate churches on a Sunday morning (10.30 in Bonhill, noon in Alexandria) with a joint evening service. One other important change from that date was that Alexandria dropped the “Parish” from its name and officially became Alexandria Old Church. In common usage it was still the Parish Church.

Bonhill North Church continued in use until 1975 when it was formally united with Alexandria Old Church as it then was. A service of union was held between Bonhill North Church and Alexandria Old on Thursday 27th November 1975, to create a single, united congregation of what was thereafter to be known as St Andrews Parish Church. The minister of the new united congregation was naturally Rev William McFarlane, and it used Alexandria Old Church as its place of worship.

Bonhill North Church was no more, although the building stood empty and increasingly derelict until about 1983, when it was demolished to be replaced by a substantial private house.

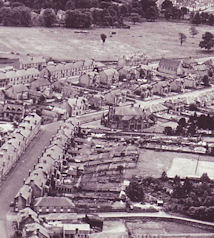

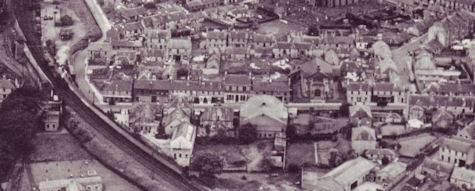

Its location right at the brow of the hill made it a difficult building to get a photograph of, and the best we’ve managed to do is this aerial photograph taken from slightly behind the Church which shows its position.

Mount Zion in 1961, the square building to-wards the bottom of the photo, with an

aluminium (prefab house) to its immediate left. (Click this image for larger version.)

Alexandria Parish Church

Alexandria Parish Church, as it was first known, still stands in Main Street Alexandria looking more or less as it did when it opened in 1840. It is now a busy place as a children’s playground. What happened in the early years of Alexandria Parish Church exemplified how badly out of touch the Established Church, run centrally from Edinburgh, had become in the period leading up to the Disruption. By the early 1800’s it was obvious to all that the growing populations in towns and villages, particularly in industrialised areas such as Alexandria, needed some form of new church organisation to support them.

Alexandria Parish Church, as it was first known, still stands in Main Street Alexandria looking more or less as it did when it opened in 1840. It is now a busy place as a children’s playground. What happened in the early years of Alexandria Parish Church exemplified how badly out of touch the Established Church, run centrally from Edinburgh, had become in the period leading up to the Disruption. By the early 1800’s it was obvious to all that the growing populations in towns and villages, particularly in industrialised areas such as Alexandria, needed some form of new church organisation to support them.

The Church decided to create new congregations around what were called “quoad sacra” parishes – essentially sub-divisions of existing church parishes into congregations based on where people now lived rather than where parish church buildings had stood from time immemorial. These quoad sacra parishes were purely church organisations, and had nothing at all to do with the civil registration and administrative parishes (which were based on the original church parishes) which have continued as they were for hundreds of years.

While it was a new creation, a quoad sacra parish had most of the status of an existing parish, including most importantly full membership of the Presbytery covering the area in which it was located, in this case Dumbarton. A quoad sacra parish was to be created in Alexandria from the existing Parish of Bonhill, and this was a sensible decision in 1840.

Alexandria Parish Church about 1900

While the Church worked out the details of these new quoad sacra parishes, they pushed ahead with new buildings which they called “Chapels of Ease”, rather than churches. Alexandria Parish Church came slightly after this and was opened as the church of a quoad sacra parish, with a minister being ordained, who seems to have been chosen by the new congregation. A new burial ground was also opened in the grounds of the church, further strengthening its position as the town’s parish church at the centre of the local community. At the time and for 40 years after, it was the only burial ground in Alexandria. There was also a real issue of status and accountability involved in this because the new quoad sacra parish of Alexandria and its newly-appointed minister were full members of Dumbarton Presbytery and participated in its formulation of church policy.

After the Disruption of 1843, the Church took cold feet and cancelled the quoad sacra status of many parishes. This included Alexandria, which was reduced to the status of a Chapel, and the minister lost his seat on the Presbytery. It’s hard to imagine anything which could have more succinctly proved the Disrupters point that the Church was both out-of-touch with its membership and arrogant in its dealing with them. The recently appointed minister soon left for pastures new, as did almost the entire church membership, which transferred to a new a Free Church congregation, 400-people strong, which was formed in Alexandria. It was a spectacular own goal by the established church.

It was not until 1866 that Alexandria regained its quoad sacra status. By then Rev William Kidd had been the minister for 22 years, having been ordained in January 1844, and went on to serve as minister for another 25 years until his death in 1891. No wonder that after 47 years of service people called it “Kidd’s Kirk”.

The Church was extended in 1906 and in that year, too, Church Halls were added in what was by then called Church St, but had previously been known as both Kirk St and Ann St. The Halls were built on the site of the former Free Church School also known as Ann St School. Among other church organisations, the Church Halls housed the 2nd Alexandria Company of the Boys Brigade, the largest in the Vale for many years, although that was a title which they eventually had to cede to 1st Jamestown.

The Wee Tin Kirk – the first St Andrew’s Church

The building of Argyll Street and Govan Drive in 1905 – 8 to house workers in the brand new Argyll Motor Works, which opened in 1906, brought a significant new population to the northern part of Alexandria, which was the furthest from any church in Alexandria. The Parish took it upon itself to address this issue and decided to build an outpost or “missionary” church to serve Argyll Street and Govan Drive. A building, whose walls and roof were made of corrugated iron, was erected at the corner of Argyll Street and North Main Street and it was called St Andrew’s Church, the first Church of that name in the Vale.

The building of Argyll Street and Govan Drive in 1905 – 8 to house workers in the brand new Argyll Motor Works, which opened in 1906, brought a significant new population to the northern part of Alexandria, which was the furthest from any church in Alexandria. The Parish took it upon itself to address this issue and decided to build an outpost or “missionary” church to serve Argyll Street and Govan Drive. A building, whose walls and roof were made of corrugated iron, was erected at the corner of Argyll Street and North Main Street and it was called St Andrew’s Church, the first Church of that name in the Vale.

Not surprisingly, everyone called it the “Wee Tin Kirk or Church”. The first reference to St Andrew’s Church which we can find so far is in October 1908, but since that reference is to a change of organist in the Church, it is reasonable to assume that it had opened some time before this. Argyll St itself was not fully opened as a thoroughfare until December 1907, so it seems probable that the Church was opened sometime in early 1908.

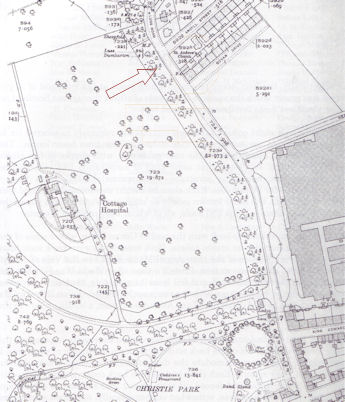

Map of location of St Andrew’s Church, at

corner of Argyll Street and Main Street

(Click to enlarge)

In February 1909 it was advertising a Sunday evening service only, at 6.30, although that did change to 4.30 within a year, as part of the PSA movement with the slogan “Brief, Bright, Brotherly”. PSA stood for “Pleasant Sunday Afternoon” and the movement began across the UK about1909, surviving in some places until the 1960’s. When it started it was aimed exclusively at young men, although people’s memories of it in the 1920’s and 30’s are of a mid afternoon service which was attended by men, women and children, with people queuing south along Main Street and down Govan Drive waiting to get in to the Wee Tin Kirk. After WW2 the Church lay unused and derelict for many years. It was still there in the 1950’s, but by May 1961 the ground on which it had stood is described as an “Unoccupied site” on the Valuation Roll’s section on churches, so it had been demolished by then.

However, the “Wee Tin Kirk” history unearthed another tale which still remains something of an unresolved mystery. For many years there had been a Church in Wilson Street belonging to the Established Church i.e. Alexandria Parish Church. It did not have a name nor did it have a number in the Valuation Roll. There is no map for the time, but earlier maps show buildings in Wilson Street and these don’t leave many possibilities about where this Church could have been located. The best option seems to be down at the north east end of the Street, on what was to become Stirling the haulier’s yard. Since Wilson Street was the northern boundary of Alexandria in the 1880’s and 90’s it seems possible that this Church, too, was a “missionary” church to the people at northern edge of the town. Furthermore, it disappears from the Valuation Rolls in May 1909 at the very same time as St Andrew’s first appears. It appears, therefore, that St Andrew’s was a straight replacement for that Church as the Parish Church’s northern outpost. It’s not impossible that it was exactly the same corrugated iron building, dismantled in Wilson Street and re-assembled in Argyll Street. Unfortunately, that particular question is proving pretty resistant to research at the moment, but we’ll keep looking.

Alexandria Old Parish Church’s last minister as a single charge was Rev Colin Munro, who served for 35 years from 1933 – 58. When he retired the Church was still called “Alexandria Old Parish Church” but that was about to change. As described above, in 1958 it became a linked charge with Bonhill North Church under the ministry of Rev William McFarlane and from then and for the next 17 years it was called “Alexandria Old Church”. In 1975 Bonhill North and Alexandria Old amalgamated under the ministry of Rev McFarlane to form a single congregation of St Andrew’s Parish Church, worshipping in Alexandria Old in Main Street Alexandria.

In March 1987 the last service was held in Bridge Street Church and Bridge Street congregation merged with the St Andrew’s Parish Church congregation in the former Parish Church. There was now only one Church of Scotland Church in Alexandria, although that situation was only to continue for another 7 years.

About 1993, the Church Halls in Church Street were demolished, which was a sign of things to come, and sure enough in 1994 the last remaining Church of Scotland congregation in Alexandria merged with the congregation of Alexandria North Church, to form a congregation which was called St Andrews Parish Church, Alexandria. It is based at the former Alexandria North Church building in Balloch. Being closed and surplus to church requirements, the old Alexandria Parish Church building on Main Street was sold to become a children’s playground known as Scallywags. The burial ground, which by that time had been closed for about 50 years, although the very occasional burial took place until the late 1950’s, continues to be maintained, like all other cemeteries and churchyards, by the Council’s Park Department.

Bridge Street Church

The 1841 break-away group from Mount Zion, which has been mentioned above, started worshipping in the Oddfellows Hall at the bottom of Random Street at its junction with John Street. This group, which retained its Relief church status, consisted of 114 members and 49 adherents, so it was a large enough congregation. In 1842 they decided to build the first church of their own, which they promptly did on the site of what was later to become the YMCA Hall and it opened in 1843. From the outset it was a liberal congregation – women members had equal voting rights with their male counterparts and the congregation owned the church buildings. Thereafter they stayed loyal to Bridge Street itself, occasionally taking another few steps up the hill, improving the quality of the building as they went. They were only in the first Bridge Street Church for 4 years before they decided in 1847 to move to a larger building across and a little further west on Bridge Street. The existing building was then sold to a church group which called itself the Independents, but which was probably the Chartist Church described below by Graham Lappin, and the Independents used it for many years. The new Bridge St Church, their second, shows all the signs of the Relief origins of the congregation, although the congregation changed it allegiance to the United Presbyterian Church when it was formed in 1847, at about the time of the move into the new building. It is square, unadorned, totally functional, and unlike the Bridge Street Church buildings which preceded and succeeded it, it is still standing and very much in use, as the Baptist Church. Both these Bridge Street churches appear in the map below of Alexandria in the 1860’s, the second of them as a United Presbyterian (UP) church.

1860’s Map of Alexandria which shows the Independent’s Church where Bridge Street

Church started (bottom right), the UP Church to which they moved (bottom middle) and

both

on Bridge Street. Top left is the Free Church on Bank Street, before being rebuilt in 1889.

(Click image to enlarge)

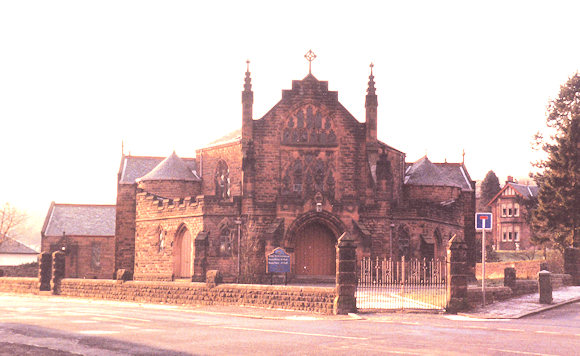

In 1908, they decided to move again, as a United Free Congregation which they had become because of another merger of the churches, commissioning a fine red-sandstone church in Upper Bridge Street. There is  no better example of how affluent the UF congregations were by then or how good were the architects on whom they could call.

no better example of how affluent the UF congregations were by then or how good were the architects on whom they could call.

In the case of the third and last Bridge Street Church the architect was the prominent Glasgow firm of H & D Barclay. This firm was not quite in the top division of 3-4 Glasgow architect partnerships at the time, but it was well up the second division. Buildings of theirs which have survived include Jordanhill Teacher Training College, and the oldest building still in use by Strathclyde University, the former Royal Technical College in George Street, Glasgow. Both are prominent red sandstone buildings which are both still fit for original purpose.

< Aerial view of Bridge Street Church 1947 (click to enlarge)

The new Bridge Street Church was a very fine building by any standards, and of an enduring design. It made excellent use of red sandstone from Locharbriggs in Dumfries-shire which blended in well with the local stone of the Middleton Street buildings and fitted perfectly into a spacious location. The builder was John Adam from Glasgow, but most of the other tradesmen were from Alexandria – William Taylor Joiner and Alex Irvine plasterer to name but two. Its service of dedication was held on Wednesday 9th June 1909, and the last service in the old church was held on the following Sunday, 6th June 1909.

It had been in decline for many years when it was decided to seek a merger with St Andrew’s Parish Church in 1987. The last service was conducted by Rev Andrew Scobie in March 1987 and then it closed for good.

Alexandria United Free Church - Upper Bridge Street.

The building lay empty while would-be developers put many designs and schemes to planners and conservation officials, attempting to meet their demands. Most gave up in disgust. In March 2000, 13 years after it stopped being a church, final closure of a sort was obtained: the building was burned down.

Bridge Street Church Pulpit and Organ

Bridge Street’s numbers had been in decline for many years before the congregation decided to seek a merger with St Andrew’s Parish Church in 1987. The last service was conducted by Rev Andrew Scobie in March 1987 and then it closed for good. The building lay empty while would-be developers put many designs and schemes to planners and conservation officials, attempting to meet their demands. Most gave up in disgust. While the building deserved its listed status, it’s hard to escape the feeling that it became a prime example of the perils of inflexible conservation. With a bit more flexibility some useful role could surely have been found for the building. In March 2000, 3 years after it stopped being a church, final closure of a sort was obtained: the building was burned down.

Bank Street or Alexandria North Church

Alexandria North Church was the congregation which decided in 1963 to make the bold decision to move out of the centre of Alexandria and build a new Church on a green-field site in Balloch. That new Church, officially opened in 1965, is now the building which hosts the amalgamated congregations from the three other Vale churches, so the move was not just timely, but has also stood the test of time.

Bank Street Church (in middle background)

The origins of Bank Street church were very much in dissent and Disruption. About 1838, 5 years before the Disruption, a group of people in Alexandria formed themselves into a congregation of what they called “Independents” and set about building an Independent Chapel in Bank Street (still called Ferry Loan at that time). Graham Lappin writes “I believe that this group had its origins with the Vale of Leven Working Man’s Association formed after the 1832 Reform Act when the newly enfranchised clergy and middle class refused to support the extension of suffrage to the working man. The Association supported the Charter and organized an alternative Church and School in the late 1830s. It eventually changed its name to the Universal Suffrage Association and drew attention to the great suffering in the Vale at the time caused by the introduction of machine printing.”

“The main actor in the Chartist Church was William Thomason who was a teacher and served as the main minister and was very active in National Chartist Politics. He was a supporter of a rather limited approach to implementing the Charter and had his run-ins with O’Connor who was in favour of more radical means to extend the suffrage. At one point some of the Chartist Clergy applied for recognition of their credentials by the Secession Church and despite the advocacy of Andrew Somerville, then Minister in Dumbarton, were turned down.”

Graham also provides us with some further information about that Church, which shows its Chartist background (Feargus O’Connor was the great Chartist leader who had addressed a mass meeting at the Public Park in Alexandria).

“Another Young Feargus O’Connor.—On Sunday last (August 2, 1840) was baptised, by Mr. Caird, in the Christian Chartist Church of the Vale of Leven, Elizabeth Feargus O’Connor, daughter of Mr. William Hays. This was the first baptism which had taken place in that place of worship.”

The Church which the Independents or Chartists had built proved to be too large for the numbers which they attracted. However, a way out of that problem was at hand.

After the Disruption of 1843, a new Free Church congregation formed in Alexandria. This was wealthy but homeless. The solution was obvious; they bought the Independents’ church in Bank Street and opened it in December 1843 as a Free Church. This church stood exactly on the site of the second one which survived until 1968, as can be seen on the image of the Map of Alexandria of 1860. (The Independents from whom it was bought by the Free Church are presumably the same Independents who bought the first Bridge St Church building, when it was vacated in 1847.)

Although we don’t have any image of this 1830’s Church, given its background as an Independents’ church, it’s a fair assumption that it would have been a pretty simple building. That is not a description which could be applied to most 19th century Free Church buildings, at least in the towns and cities, and by the late 1880’s something more grand was probably called for, but by whom? The local leading member of the Free Church at this time was James Campbell of Tullichewan Castle and Estate. His father William, who founded the family fortunes with his Glasgow department store, had paid for the building of Millburn Church over 40 years before. Carrying on that family tradition, James now stepped forward to pay for a replacement building for Bank Street Free Church. We don’t know whether he volunteered or whether he was asked by the congregation to pay for the building, and it doesn’t really matter anyway.

That, however, was by no means the end of the Campbell family involvement with the building. The firm of architects responsible for its design was one of Scotland’s leading architectural partnerships at the time – John Burnet Son & Campbell. The Campbell in the firm’s title was John Archibald Campbell, whose grandfather was William Campbell and whose uncle was therefore James Campbell, while William Ewing Gilmour was married to his cousin Jessie Gertrude Campbell, who was James’s third daughter. John Campbell was an excellent prize-winning architect in his own right, but as the Dictionary of Scottish Architects puts it, being a member of the Campbell of Tullichewan family gave him “a connection which brought a number of commissions in and around Alexandria.” Just before starting on the Bank Street Church he had finished designing the Ewing Gilmour Institute for Ladies (now the Masonic Temple) for his cousin and her husband, William Ewing Gilmour, who was paying for it, and shortly after he finished work on the Church, in 1891 he designed the new Tullichewan Arms Hotel at Balloch for his uncle James, who was its first owner. There was obviously a wee bit of nepotism in all of this, but since it was his uncle and cousin who were paying for the buildings, including the architect’s fees, they were perfectly entitled to choose whoever they liked, especially if he was an architect of the first rank, as John Archibald Campbell was.

The new Tullichewan Arms c 1900

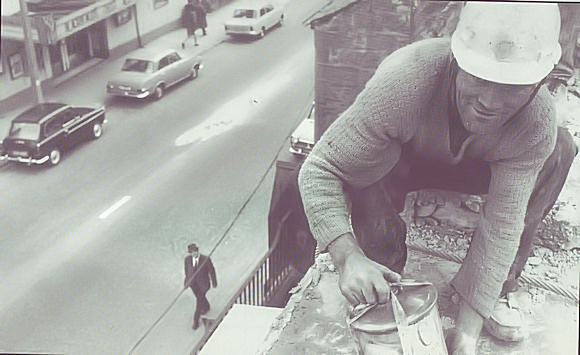

Fortunately, we have a lot more information about Bank Street Church’s construction. When the new Church was opened in 1889 it was decided to put a time capsule into the new building. Amongst other things, this contained photographs of ministers, the builder, William Barlas, the benefactor James Campbell and also a copy of John Archibald Campbell’s plans for the church. When the Church was being demolished in 1968, the time capsule was retrieved and later sealed into the new church at Balloch.

During the demolition of Bank Street Church in 1968, the time

capsule is retrieved. Note the Strand Cinema in the background.

Before being sealed in, photographs were taken of the original architect’s plans, and thanks to Morag Bain we are able to display these below. The plans are discoloured by dampness seeping into the capsule over the years, but enlarging the image shows much of the detail. The most striking thing is the beauty of the design. With the passage of almost 50 years since the building was vacated, it is very difficult for former members of the congregation of what became, after 1929, Alexandria North Church, to remember exactly how much of the design actually made it into the build, but most of it seems to have done so. These images are the only ones we have for any of the plans for the major buildings from the hey-day of the Vale’s public building boom in the late 1800’s.

Architect’s plans for Bank Street Church

(Click to view)

The Longitudinal Section | The Ground Floor Plan | The Gallery Plan | The Facade

The other advantage of the plans is that they are the only close up image of what the front of the church actually looked like. Because it was on the street, with a wall on the opposite pavement, it was a difficult building to photograph from the front, and we have no photos of the whole frontage taken head-on, as it were.

The other advantage of the plans is that they are the only close up image of what the front of the church actually looked like. Because it was on the street, with a wall on the opposite pavement, it was a difficult building to photograph from the front, and we have no photos of the whole frontage taken head-on, as it were.

We do have a side view taken looking up Bank Street which shows the roof and the small bell tower, and also an aerial photograph taken from across the Leven in 1947 which shows the Church’s position and its facade quite clearly.

(Click image to enlarge)

When Rev James Robertson left in April 1958, the North Church entered into a 7 year period of linkage with Bonhill South, firstly with Rev Alan Hasson as minister of both Churches and then with Rev John Taylor of the North Church as minister. The link was terminated in April 1965 when Alexandria North moved to Balloch. As we’ve seen above, Bonhill North and Alexandria Old were already linked by 1958, and Bridge Street and Bonhill Parish Church were also soon to establish a link under Rev Muir Haddow. The decline in church membership had been matched by a decline in people entering the ministry, so by the early 1960’s a shortage of ministers was as critical as a shortage of members.

Aerial view from above Dalmonach to Bank St showing the church facade

and the back of the Strand Cinema, 1947 (Click to enlarge)

Against that background, it took some courage to look to the future with optimism and resolution, but that is exactly what the Alexandria North Church congregation did. In 1963 the congregation decided to move to the Church’s present site in Lomond Road, Balloch. The impending redevelopment of Alexandria Town centre was clearly a factor, as was the drift of people from the centre of the Vale, and there is a recollection that the discovery of dry rot may have played a part. However, it was not inevitable that the Church would have to be demolished. As late as March 1965, when the move was about to take place, the County Council to whom the building had been sold, was saying to the Lennox Herald that it was not yet certain that the building would have to be demolished to make way for redevelopment. If it were not demolished, they said, it may be used as a public hall, at least on a temporary basis.

Looking at the line of the new road and the wasted space on the north east side of the road, the new road could easily have been slightly re-aligned to allow for the survival of the church building. Such is not the way of planners and developers, however. A footbridge, now demolished, and a couple of anonymous and charmless buildings which may soon go the same way as the footbridge, were deemed more suitable than a building of quality design and build.

Further confidence was shown by congregation when they purchased a new manse, in Luss Road Balloch, a few hundred yards to the north of the new church. This was a particularly striking acquisition, because for nearly 30 years it had been one of the best known houses in the Vale as the home of Mr Ernst Hofstetter, Managing Director of the nearby British Silk Dyeing works and also the Swiss Consul for Scotland. Because of his diplomatic status, “Wee Hoffie” as he was affectionately known, flew the Swiss flag from a flag pole in the front garden. By 1965 Mr Hofstetter had retired and had long ago moved to Drymen. The American company which had taken over the BSD in 1960, decided that it had no further use for the house and sold it to Alexandria North Church. The striking house made an ideal partner as a manse for a brand new church.

When it was opened it’s white colour and elegant simple design quickly earned it the nick-name of the Ponderosa, the ranch house in the then-popular TV series Bonanza. It was very much an affectionate nick-name which helped the public to identify with the church in its new location in no time at all, and it is perhaps a little surprising that it has now dropped out of circulation. All four churches were formed over a period of 12 years or so in the 1830’s and 1840’s, and the last to be established, just, has proved to be the most enduring, offering a home to the survivors of the other three.

Jamestown Parish Church

The history we are providing here is a downloadable PDF document, which is a word-for-word transcription of the history of Jamestown Parish Church from its opening in 1869 until 1934. It was written by the incumbent minister in 1934, Rev Dr MacGregor who had been the minister since 1925. Although we’ve changed the format a little and we couldn’t use most of the photographs in the original history, everything else is as it appears in Dr MacGregor’s History (note the spelling of his name on the document).

Its not really a full history of the congregation, but more an account of the fund-raising for the building of the church and then the manse, church hall and the acquisition of a harmonium and eventually the organ. It therefore features a few of the “great and the good” of the Vale and surrounding areas at the expense of the great majority of the people who worshipped in and managed the Church.

Its not really a full history of the congregation, but more an account of the fund-raising for the building of the church and then the manse, church hall and the acquisition of a harmonium and eventually the organ. It therefore features a few of the “great and the good” of the Vale and surrounding areas at the expense of the great majority of the people who worshipped in and managed the Church.

In its deferential tone and in the language used it seems quite dated now, which is a little bit surprising because Dr McGregor is well remembered by many, not just in the congregation, but also in the population at large, and is thought of as a modern minister, in thought if not in attire - his habitual black suit giving the impression of severity.

We would treat a few of the historical references about non-church matters quoted by Dr MacGregor with some caution, but we’ve got a lot of sympathy with him about that, since he had few sources on Jamestown matters, outside of the Church records, readily available to him.

The single photograph from the original which we have been able to use is of the elders with Dr MacGregor in 1934. A copy of it was provided by Billy Scobie whose grandfather, W Scobie, appears in it.

The photos of the Church and Milton Terrace are not the same as those which appeared in the History, while the photos of old Jamestown from the dam and the Free Church School are additional, since there were no photos of either in the History. One other image was added of a wedding scene from the 1890's, which includes the Rev. Daniel J Miller, the minister at that time. Download Here >