India Street and the Vale's Indian Connections

Our thanks are due to local historian William Scobie for writing this article and allowing us to include it.

Our thanks are due to local historian William Scobie for writing this article and allowing us to include it.

India Street in Alexandria is a small, red sandstone terrace by the Levenside, beside the gate of the old Alexandria textile works – “The Craft”. It is surrounded by some of the remaining old brick factory buildings and the Lomond Industrial Estate.

The general association of the town with India was through the Vale of Leven’s Turkey Red textile dyeing industry, and the specific connection with this particular location was through the old Croftengea and Alexandria Works.

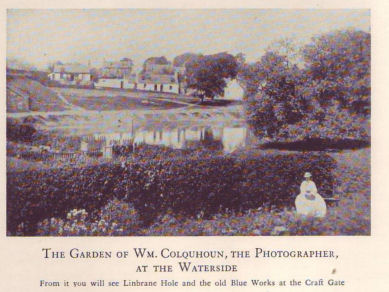

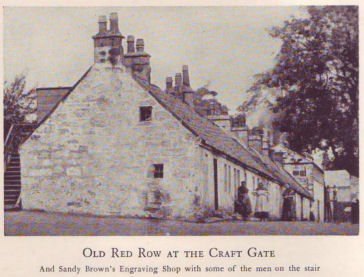

The image above is of the Old Red Row that was beside the Craft Gate before India St. was built. the other image is taken from the opposite side of the Leven at the Linbrain Hole with the same buildings in the back ground.

(Place mouse pointer over images to enlarge.)

The East India Company

The long, fascinating and profound relationship between Britain and India was effectively initiated by a Scot. Although the East India Company had been founded by a charter from the English Queen Elizabeth in 1599, the Company’s initial interests lay with the spices of the East Indies. It was King James, Sixth of Scots and First of the United Kingdom, who sent an emissary, in 1612, to the court of the Mughal emperor to establish the right of British merchants to found a trading post at Surat (a place famed for printed textiles) in India.

According to most accounts the Company was not interested in military conquest as such, but throughout the 17th century, in the process of extending its Indian presence, it became involved in military episodes, sometimes for and sometimes against, native rulers in defence (as the Company saw it) of its commercial interest. By the end of the 1600s the East India Company had incorporated  Bombay and Calcutta, and had divided its territory into the three Presidencies of Madras, Bombay and Bengal.

Bombay and Calcutta, and had divided its territory into the three Presidencies of Madras, Bombay and Bengal.

The following century involved significant conflicts with other European colonial powers, mainly France, as well as with native princes. The victory of Robert Clive (a company writer turned soldier - pictured left) over the Nawab of Bengal, at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, was the turning point, and within a few years the East India Company was well on its way to being in charge of the greater part of the Indian sub-continent.

Between the years 1752 and 1767 George Scott, brother of Charles Scott of Dalquhurn and Woodbank, was in India. After his death in London, immediately following his return from India, George was buried at Dalquhurn and around his memory there arose the apparent fantasy of the Black Lady. The story was that George had brought an Indian woman home to Dalquhurn. Research indicates that this has no basis in fact, but the suggestion that George Scott was an East India Company man is perfectly credible.

Calico and Turkey Red

One of the commodities introduced to Britain by the East India Company was a hugely popular type of cotton – calico (named after the town of Calicut on the Malabar coast). As early as 1768 John Todd & Co. had established a calico printing work at Levenfield in the Vale. (John Todd was the husband of George Scott’s niece). Two years later William Stirling founded the calico printing works at Cordale, then in 1790 his company set up a bleachfield at Croftengea. Stretching to the north of India Street were the Croftengea Works, the Charleston Engraving Works and the Levenfield Works.

The textile industry transformed the Vale of Leven from a scattering of small rural villages to a highly populated, industrial community. It was Turkey Red dyeing which fully established the reputation and prosperity of the Vale. The secret of Turkey Red was brought to Scotland by Frenchman, Pierre Jacques Papillon, in 1785. Dalquhurn Works in Renton began experimentation with the process in 1816, and William Stirling & Sons went into Turkey Red production in 1828. The first product using this method was the bandana handkerchief, which was a calico version of the bandhanas of India – brightly coloured silk with white spots. The original basis of Turkey Red dye was the vegetable madder, rubia tinctorum. (There is evidence of cotton dyeing with madder in India as early as the 3rd millennium B.C.). From 1868 the synthetic alizarine was considered an improvement.

In 1809 Croftengea was purchased by Messrs. Turnbull & Jones, and it was here, in 1827, that the Turkey Red process was first made commercially successful. Eight years later the works were taken over by John Orr Ewing & Company, and ten years after that the calico printers Robert Alexander & Co. took control. In 1860 Croftengea was back in the possession of John Orr Ewing & Company and it was at that time that, with a workforce of 1000, it was amalgamated with the  Levenfield Works. The Vale of Leven became the leading world producer of Turkey Red textiles. From the railway siding at Croftengea a vast amount of cloth was exported throughout the globe – to Africa, China, South-East Asia, Pacific Islands, South America… but the main market was India.

Levenfield Works. The Vale of Leven became the leading world producer of Turkey Red textiles. From the railway siding at Croftengea a vast amount of cloth was exported throughout the globe – to Africa, China, South-East Asia, Pacific Islands, South America… but the main market was India.

David Bremner in his Industries of Scotland (1869) tells us –

“As most of the goods are for the Indian market the colours are somewhat ‘loud’ and the designs peculiar. The dress-pieces made for the people of the Hindu religion have a broad border of peacocks round the skirt, the upper part bearing a spotted diaper pattern. The ground work of all is Turkey red, but the birds and other designs are produced in blue, yellow and green. The Mahometans consider it sinful to try to imitate nature too closely; and though peacocks figure in the designs prepared for the ladies of that faith, they are drawn in the rudest fashion and worked out in mosaic.”

* * *

In the middle of the nineteenth century seventy-five percent of the cotton for the United Kingdom’s textile industry was coming from the United States of America. However, a disastrous cotton crop failure in 1846 caused British textile bosses to reconsider India as a source of supply, resulting in a massive increase in the use of Indian cotton. The American Civil War had a similar effect.

Bonhill to Madras

Patrick Boyle Smollett of Bonhill was the brother of the man in honour of whom Alexandria’s Fountain was erected. Patrick was the Member of Parliament for Dunbartonshire between the years 1859 and 1868. He was instrumental in the building of the Smollett Mausoleum at St. Andrew’s Church in the Vale, and he granted the land for St. Mungo’s Scottish Episcopal Church at the south end of Alexandria. Around the age of twenty he sailed for India to take up an appointment in the Civil Service of the East India Company’s Presidency of Madras. (The term “civil servant” originated with the East India Company.) For five years he was secretary to the Board of Revenue. In 1843 he became the Agent to the Governor of Vizagapatam – an extremely influential role. On his return to the Vale in 1859 he took up domestic politics.

Patrick Boyle Smollett of Bonhill was the brother of the man in honour of whom Alexandria’s Fountain was erected. Patrick was the Member of Parliament for Dunbartonshire between the years 1859 and 1868. He was instrumental in the building of the Smollett Mausoleum at St. Andrew’s Church in the Vale, and he granted the land for St. Mungo’s Scottish Episcopal Church at the south end of Alexandria. Around the age of twenty he sailed for India to take up an appointment in the Civil Service of the East India Company’s Presidency of Madras. (The term “civil servant” originated with the East India Company.) For five years he was secretary to the Board of Revenue. In 1843 he became the Agent to the Governor of Vizagapatam – an extremely influential role. On his return to the Vale in 1859 he took up domestic politics.

* * *

A Scot who made a huge contribution to the development of Indian affairs was Lord Dalhousie. As Governor-General (1848-1856) he was the youngest man ever to rule India. He initiated a vast programme of public works and civil engineering, with much road-building and, most significantly, he introduced the railway.

Soldiers of the Crown

In 1857 the horror of the Indian Mutiny broke out. There were various causes. Many Indians had begun to fear that the rule of the East India Company by then posed a serious threat to their traditional caste system and to their religious beliefs and customs. The rights of some princes and land reforms were contentious issues. It was not a national rebellion, being confined largely to Northern India, and many Indian soldiers loyal to the Company helped to put it down, but the shambles of the Mutiny led to an act of parliament which, in 1858, decreed that thenceforth India would be ruled directly by the British Crown.

A considerable army was required to defend this imperial possession. In 1863 sixty-two thousand British soldiers served alongside one hundred and twenty-five thousand Indians troops loyal to the Queen. The native soldiers were drawn from many of the different peoples of the sub-continent – Marathas, Pathans, Rajputs, Sikhs, Brahmins… and Gurkhas. Robert David Colquhoun of Tullichewan in the Vale of Leven had raised the Kemaon Battalion of Gurkha Rifles in 1815. (Arising from this, in 1928, permission was granted to the pipers of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles to wear Colquhoun tartan.)

Many a man from the Vale of Leven soldiered in India, such as Bernard O’Hare of Renton who served with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and died in Rawalpindi in 1896, inspiring these lines by Katherine Drain of Alexandria -

"And while he of Home is dreaming

On those lonely, distant plains,

Alas! The burning heat is scorching

The very life-blood from his veins."

Missionaries

There is little doubt that Victorian Britons entertained the notion that their right to govern India was God-given. Objectionable though such sentiments are to the modern ear, William Wilberforce (hero of the abolition of slavery) probably spoke for most of his countrymen at the time when he said – “Our religion is sublime, pure and beneficent. Theirs [Hinduism] is mean licentious and cruel.” To the imperialists Civilization and Christianity were synonymous. They believed that they could do the Indian people no greater service than convert them to Christ.

In its earlier years, for commercial and practical reasons, the East India Company had effectively discouraged any missionary activity, but, by an act of parliament, from 1813 evangelisation was encouraged on Company territory. The Church of Scotland (for example) sent missionaries to Bombay in 1829, to Calcutta in 1830, to Poona in 1834 and to Madras in 1837. However, Queen Victoria, who in 1877 would be made Kaisar-i-Hind, Empress of India, declared after the Mutiny –

“Firmly relying ourselves on the truth of Christianity and acknowledging with gratitude the solace of religion, we disclaim alike the right and the desire to impose our convictions on any of our subjects…”

Although the various Christian denominations brought much to India by way of English language education, Indians by and large proved very resistant to conversion. It should be remembered that India gave the world major religions like Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. At present only between 2 to 3 percent of Indians are Christian.

As in commercial, administrative and military spheres, the Vale of Leven made its contribution to the evangelising endeavour in India. One instance being the case of the Rev. John Wood who was inducted to Millburn Church, Renton, in 1928, but went on to a ministry in Calcutta.

From Cordale to Delhi

His father was a slavery abolitionist from Inveraray, and his grandfather was a minister of the Church of Scotland. Thomas Babington Macaulay is reckoned to have affected the history of India more than any other individual Briton. Remembered more as an author, it was his education policy which was responsible for much of the westernising of India, and his legal reforms are regarded as the foundations of modern Indian law. Macaulay’s penal code was enacted in 1860 – the year in which John Orr Ewing & Co. amalgamated with the Levenfield Works. It was in this decade that John Matheson Junior left Cordale for a tour of the sub- continent.

In 1846 John Matheson took up a position with William Stirling & Sons at Cordale in Renton. Thirty years later he was effectively the sole partner in the firm and for a time he was Chairman of the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce. While living in Cordale House, Renton, Matheson wrote England to Delhi. The book was an account of his tour of India. Mainly a business trip, it included a great deal which was educational. It remains a fascinating read. In what is essentially a travelogue, Matheson gives the reader his impressions of the diversities of Indian society, culture and religion. With regard to the central reason for his journey – the textile business of the Vale of Leven – he has this to say –

“The process of bringing home cotton from India in one ship and returning it in another, manufactured into jacconet or cambric cloths, may to the inexperienced appear to involve a considerable loss of both labour and capital; but… [Matheson goes on to explain that with the low costs of freight, and India’s lack of coal to fuel the necessary industrial machinery]… it is only reasonable to conclude that the field is becoming more and more our own in the gradual extinction of the hand-loom, and those other rough old modes of native manufacture which still hold their ground in the more retired rural districts.”

Matheson tells us that British trade with India had quadrupled in the preceding 25 years, and he stresses the importance of the introduction of the railways. He uses a memorable phrase when speaking of the enormous quantity of cotton cloth produced for the Indian market – “…sufficient in length, let us say, to girdle the two countries in a calico bond of union.”

* * *

India Street appears (with house numbers up to 33) in the Valuation Roll for 1886/87. However these houses – which were previously known as the Red Row – were demolished, making way for the fine new terrace of 1891, at the Craft Gate, which remains to this day.

The U.T.R.

In 1897 the three major Vale of Leven textile firms – William Stirling & Sons, John Orr Ewing & Co. and Archibald Orr Ewing & Co. amalgamated to form the United Turkey Red Company Ltd. They employed around 6,000 people and the buildings of the combined companies extended over an area exceeding thirty acres. The Alexandria Works became the U.T.R.’s main factory.

In the same year, however, the Government of India imposed import dues in order to boost the sub-continent’s own industries. The consequence of this was an overcapacity in the Vale’s U.T.R. Fortunately this did not affect the industry’s viability too severely. It was during the nineteen-twenties and thirties that real economic hardship came to the community. The first Indian cotton mill had been established in Bombay in 1854. By 1935 there were 365 Indian mills, but the Vale’s main foreign textile competitor was Japan. In 1921 and 1922 the U.T.R. paid no dividend to its shareholders. Ferryfield, Dillichip and Milton were the first local works to close, followed by Levenbank and Cordale.

Gandhi and Independence

Scots played a full part in every aspect of the “Raj” – as merchants, administrators, politicians, missionaries, doctors, engineers and soldiers. They also contributed to the process of achieving Indian independence. Allan Octavian Hume came of a Scottish family. With a letter written to the graduates of Calcutta University he launched the Indian National Congress in 1885. This was to be a vehicle for eventual Indian home rule. Other Scots founder-members of the I.N.C. were William Wedderburn and Sir John Jardine.

Scots played a full part in every aspect of the “Raj” – as merchants, administrators, politicians, missionaries, doctors, engineers and soldiers. They also contributed to the process of achieving Indian independence. Allan Octavian Hume came of a Scottish family. With a letter written to the graduates of Calcutta University he launched the Indian National Congress in 1885. This was to be a vehicle for eventual Indian home rule. Other Scots founder-members of the I.N.C. were William Wedderburn and Sir John Jardine.

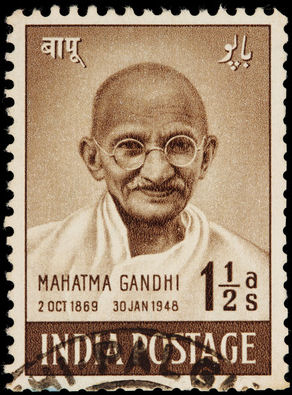

Decorated for his services to the British Empire in the Boer War and in the Zulu War, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi did not at first appear a very likely hero of Indian nationalism, but he was a profoundly spiritual man (a Hindu much influenced by the New Testament) and a political agitator extraordinaire. He became leader of the Indian National Congress and preached non-co-operation with the British. In 1921, during a visit to India by the Prince of Wales, Gandhi demonstrated his policy of swadeshi, by inciting a crowd to set fire to a mound of imported clothing. He advocated that all Indians should wear khadi – homespun cloth (the spinning-wheel became a personal symbol). Gandhi’s boycott hit the Vale’s textile industry hard over the next two decades, but the United Turkey Red held out until eventual closure in 1960.

The process which brought about Indian independence was complex and painful. With the Government of India Act of 1935 the British made it clear that they were leaving – it was just a matter of time. The Second World War took priority for six years. The principal bodies concerned in the independence negotiations were the Indian National Congress (which was supported for the greater part by the Hindus), the Muslim League and the British Government. The leading personalities were Gandhi and Nehru (for the Congress), Jinnah (for the Muslim League) and Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy (for the British). The sub-continent, partitioned into India and Pakistan became independent at midnight on the 14th of August 1947.

Mutual Respect

In any discussion of the historic relationship between Britain and India there is always a temptation to moralise in a way that can be out of place. Let it be sufficient to say that although the main motive for British involvement in India was always primarily the pursuit of profit, there was very much more to it than simply a colonial power cynically exploiting a subject people. The long encounter between Briton and Indian was by no means devoid of mutual respect, or even something deeper and more noble. Each changed the other forever. It surely tells us something that during the Second World War, almost on the eve of independence, two and a half million Indians volunteered to fight alongside the British against fascism. The interface of British and Indian cultures gave rise to incalculable benefits for both, with the Western world being greatly influenced by much of Indian religious and philosophical thought.

* * *

Returning then to that little sandstone terrace by the Craft Gate, with its bright red post-box bearing the monogram of George VI, the last “Emperor of India”. Just a mile downstream, at Millburn, in the summer’s evenings, Scots-Indians and Scots-Pakistanis may now be seen playing for the Vale of Leven Cricket Club. Who would have imagined such a thing when the first calico came to Croftengea?