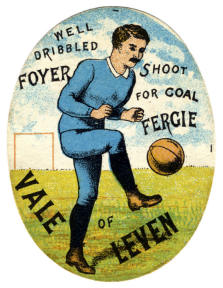

Football in the Vale of Leven - 1880’s

As the 1880’s began, not much of that was yet apparent but within a decade all of these factors had impacted the Vale, none of them positively. The Vale was still a top Scottish club for another 10 years or so. It still did well in the Scottish Cup, it regularly played against the best English teams, beating them more often than losing to them, and it still provided players for the Scottish international team. So the glory days were far from over and the 1880’s provided plenty for the Vale supporters to be happy and optimistic about, as well as a few things at which they could vent their spleen. And, of course, in 1888 they moved into a beautiful new stadium, Millburn Park, where Vale of Leven FC still plays.

As the 1880’s began, not much of that was yet apparent but within a decade all of these factors had impacted the Vale, none of them positively. The Vale was still a top Scottish club for another 10 years or so. It still did well in the Scottish Cup, it regularly played against the best English teams, beating them more often than losing to them, and it still provided players for the Scottish international team. So the glory days were far from over and the 1880’s provided plenty for the Vale supporters to be happy and optimistic about, as well as a few things at which they could vent their spleen. And, of course, in 1888 they moved into a beautiful new stadium, Millburn Park, where Vale of Leven FC still plays.

The decade began optimistically enough on the park. Although beaten in the 2nd round of the Cup in 1881 by Dumbarton, who had become something of a Cup bogey team for the Vale, they went on to have a successful season in other campaigns. They played and beat two of England’s leading teams, Bolton Wanderers and Blackburn Rovers and in June 1882 they gained revenge over Dumbarton by beating them 1-0 in a replay of the final of the Glasgow Merchants Charity Cup in front of 6,000 people. It was the only time which the Vale won the Charity Cup, a competition which was devised by the Glasgow clubs in the years when the Vale was monopolising the Scottish Cup. So quite unintentionally the Vale was responsible over the years for raising tens of thousands of pounds for charity, a point which many of the Vale’s Glasgow friends happily reminded them over the years.

The following season, in the middle of rebuilding their team, the Vale got to the first of three successive finals. In 1883 they met Dumbarton. The first game was drawn 2-2, but in the replay Dumbarton beat the Vale 2-1. This was first and only occasion on which Dumbarton won the Scottish Cup, although there are still some Sons supporters who say that they live in hope, and why not?

1883 – 84 was an eventful season of high drama and excellent performance, as well as dreadful anti-climax. North Street Park was never busier and its record attendance was set during the Vale’s cup run that season. In the quarter final the Vale met their deadliest rivals, Renton, who had already knocked out the holders Dumbarton. In front of what is only described as a “huge” crowd at North Street Park, Vale beat Renton by the surprisingly comfortable margin of 4-1. This took them to a semi-final, again at North Street Park (there were no neutral venues for semis in those days) against a Rangers team just reaching its prime.

With all of the history between these two clubs, and the bitterness on Rangers’ part at previous results, you can just imagine the tension in the build up to the game. It certainly got the public’s attention. Special trains had to be laid on to bring the Rangers’ support down to Alexandria, and in fact the railway system couldn’t cope with the rush. The start of the game had to be delayed by 35 minutes to allow the last train to arrive and its supporters to get into the ground. The official attendance was given as “over 6,000”, but it was much more than this. In any event, 6,000 became the record attendance at North Street Park. In a well contested game Vale ran out 3-0 winners and headed for the final with another team with whom they had had an up and down relationship – Queen’s Park. Events surrounding the final did not improve it.

The game was due to be played on Saturday 23rd March 1884. However by Wednesday 20th it was clear that because of bereavement, illness and injury, 3 Vale first team players would be unavailable, and to make matters worse, their 3 reserves were also injured or indisposed. The Vale contacted the SFA on the Wednesday asking for a postponement, but the SFA refused. From here on in, the Vale should have handled matters more effectively. Instead of immediately laying all the facts before Queen’s Park, who might well have agreed to a postponement at this stage, they simply asked them to postpone the game, with no explanation given. Queen’s who had a full schedule of games, including an English Cup Final, refused and you can’t blame them for that.

The game was due to be played on Saturday 23rd March 1884. However by Wednesday 20th it was clear that because of bereavement, illness and injury, 3 Vale first team players would be unavailable, and to make matters worse, their 3 reserves were also injured or indisposed. The Vale contacted the SFA on the Wednesday asking for a postponement, but the SFA refused. From here on in, the Vale should have handled matters more effectively. Instead of immediately laying all the facts before Queen’s Park, who might well have agreed to a postponement at this stage, they simply asked them to postpone the game, with no explanation given. Queen’s who had a full schedule of games, including an English Cup Final, refused and you can’t blame them for that.

So the game was scheduled to go ahead on the Saturday, but the Vale did not show up. It’s hard to have much sympathy for them at this point. OK, they had a much weakened team and may well have been beaten, but that’s all part of the game. However, what happened next retrieved a lot of sympathy for the Vale, allowing them to portray themselves to their public, and many others, as victims and martyrs to the cause, doubly wronged by an establishment dominated by Queen’s in particular and the other Glasgow clubs in general.

The Cup was not just awarded to Queen’s because of Vale’s no-show; the matter had to be officially decided by an SFA committee. That committee was chaired by the President of the SFA, who also happened to be a Queen’s Park man. He did not excuse himself from proceedings on the grounds of a vested interest, but took a full part in the meeting. That the matter was by no means clear-cut and that there was a lot of support for organising another game was shown by the narrowness of the vote – 7-6 in favour – to award the Cup to Queen’s. The Vale may have lost the vote and the Cup, but the conduct of the meeting by the Queen’s chairman and the attitude of the other Glasgow clubs present at it, handed much of the moral high ground back to the Vale. There were mutterings in the press about renaming the SFA the “Queen’s Park and Rangers Association”. That accusation of dominance was quite customary as far as Queen’s were concerned, but in 1884 it was new for Rangers to be so labelled.

Having gained a hillock of moral high ground, the Vale then used that vantage point to hurl bricks down on Partick Thistle, whom they saw as having reneged on a promise to vote for the Vale in the Committee meeting. The Thistle man on the Committee was the representative of the Glasgow clubs, and he afterwards claimed that he could not vote against a Glasgow club, apparently regardless of the rights and wrongs of the case. Since there was no way they could get back at Queen’s that season, Partick had to do as the surrogate enemy. The Vale had arranged a Club match against Thistle which they cancelled at the last possible minute, making it quite clear to Thistle why they were doing so. This probably made the Vale officials feel better, but it didn’t win them any more friends in Glasgow, not that they thought that they had many there anyway at this time. You can understand why people thought the that the Vale could be “touchy” and “difficult”.

Again in 1884-85 Vale got to the Cup final where they met Renton in front of the smallest crowd so far to watch a Cup Final. The game ended in a goalless draw, and in the replay Renton outplayed the Vale to win 3-1. At the post-match banquet, Vale added a new feature to their already considerable range and capacity for dispute – some Vale officials verbally abused the referee and his two umpires, with what were described as “caddish insults”. They at least had the good sense not to direct any of the insults at their Renton opponents, who it can safely be assumed would not have shown the restraint of the referee and umpires. Mind you, “Caddish” and the Vale aren’t words which you would expect to find in the same sentence; adding Renton is well beyond belief.

The last days of the all-Amateur game

In 1884 the game was still officially amateur in both Scotland and England. However, by this time “shamateurism” was already in full swing, by which was meant that players were found good, overly-paid jobs by clubs as an inducement to sign for them. Although it happened in Scotland, there was more opportunity for it in England. By September 1884 the Vale had already suffered from it when 4 of their players left to play for Burnley, including the much-admired Sandy McLintock. Players earning about 18 shillings (90 pence) per week in a factory in the Vale could expect to get £2 - £5 in England. Who would not be at least interested?

The SFA were alive to the potential problem this could cause Scottish clubs, especially clubs in smaller centres of population with smaller “gates”, and in a move that was meant to discourage players from moving south, in December 1884 they drew up a blacklist of players who had left Scotland to play professionally in England. They were declared ineligible to play for Scottish clubs again without the specific permission of the SFA, and in an additional move in early 1885 Scottish clubs were barred from playing against English professional clubs.

Strictly speaking, these moves were theoretical, because English football was supposed to be still amateur at this time, but everyone knew what the reality was. In any event, the English FA legalised professionalism in July 1885, and that upped the pressure on the Scottish clubs. However, the SFA resisted the temptation to follow England into professional football at this time (it didn’t legalise it until 1893, 3 years after the formation of the first Scottish League) so every Scottish club and every Scottish-based player was supposed to be amateur. Other than out-of-pocket expenses, clubs were not supposed to pay players anything. In to-day’s well used phrase “Aye, right”.

“My word of honour” - The Hibernian Affair

In season 1886-87 the Vale were able to expose the fiction of amateurism practiced by Hibernian in particular, but judging from the comments of many other SFA members, it’s a fair assumption that many clubs were paying players in contravention of the rules. That season the Vale won through to a semi-final against Hibernian without too much difficulty. The game was eventually played in Edinburgh in January 1887 (bad weather delayed it), and Hibs won 3-1. The Vale lodged a number of protests against the result immediately after the match. The most important of these was an accusation of professionalism against Hibs.

As soon as the protests were made, they were handled by the appropriate SFA committee, which met within a few days to consider their merits. There were two concerns voiced by some members of this committee, neither of which suggested that the facts in the case were going to be given a fair consideration. The first was that some committee members felt that because a date had been set for the cup final, time was of the essence and the matter had to be dealt with in the shortest possible time. The second was that if the Vale were proved right in their accusation of professionalism, then every other Hibs opponent from the first round onwards would have to be re-instated and a whole series of new games played throughout a succession of rounds. Some members made it clear that no matter what Hibs had done, they did not want the competition to be delayed or replayed. Hardly the fairest approach to considering the merits of the Vale’s protests.

All of the other protests were quickly dismissed by the SFA committee, but that of professionalism was not. After a 5 hour meeting at which the Hibs secretary, Mr McFadden, was grilled about payments to players, which he totally denied, it was decided to give the Vale 10 days to add substance to the accusation. The 10 days was actually the time limit which the Hibs secretary, McFadden, had asked be set on the investigation and this was further evidence of the less than even-handed approach of the Committee.

Two things are clear from that meeting. Firstly, the Hearts representative on the Committee had information, perhaps common gossip in Edinburgh, about possible payments to specific Hibs players, and he wasn’t going to let the matter just die quietly. Secondly, many Committee members thought that the 10 day limit would effectively close the matter down by not giving the Vale enough time to collect anything other than hearsay evidence. It’s probably fair to say that while there were those on the Committee who were happy to see Hibs mildly embarrassed, nobody expected or hoped that the Vale could prove their case with substantive evidence. The Committee members thought that they had kicked the ball into the long grass. However, they should have known better, since to slightly paraphrase Dr Johnston’s phrase about Scotsmen in general, “no one would mistake a Valeman with a grievance for a ray of sunshine”.

Even to-day, with modern high quality video evidence we have seen in many cases of monetary inducements either being offered or solicited in a number of different sports that proving illegality is notoriously difficult. 120 years ago it was infinitely more so, especially with the time limit set by the Committee. However, the Vale acted with speed and energy. They promptly hired a private detective to investigate Hibs. This was very daring and modern – Sherlock Holmes had not yet been created and private detectives were few and far between in Britain. Perhaps the most surprising thing about the whole affair was the amount of evidence which this detective managed to unearth in the few days available to him.

At the reconvened meeting of the SFA Committee on Thursday 10th February 1887, the private detective produced witnesses who claimed that:

• The best Hibs forward, Willie Groves, was publicly boasting, and had boasted to them personally, that Hibs paid him

• The whole Hibs team seemed not to be at work in the week before the game, and spent their time in a hotel in Edinburgh lunching and lounging about. The hotel owner appeared in front of the Committee and gave evidence to that effect.

• Witnesses had been threatened with violence if they gave evidence of other payments made to Hibs players. To this piece of testimony the Hearts representative added his own statement that he too had been threatened by Hibs people for offering evidence of payments

The detective produced a number of letters and statements from people who couldn’t attend the committee meeting, but the committee refused to admit them as evidence.

Mr McFadden, the Hibs Secretary, was now put on the spot by the most damning piece of evidence, which proved the Vale’s case beyond any reasonable doubt. That evidence came from Hibs themselves in the shape of their cash book. The SFA had had anti-professionalism rules for a few years which required each club to have its cash book ready for inspection at a moment’s notice. The Committee asked Hibs to produce the cash book covering the last three years. During these three years there had been a number of different Hibs treasurers and secretaries who would all have made entries of income received and payments made. It should have consisted of a number of different sets of handwriting and inks. Instead, the entries in the Hibs cash book given to the Committee were all written in the same hand and looked as if it had all been written on the same day. The hapless Mr McFadden said he did not know why that was the case, because, he said, the cash book would have been posted up week by week. “I give you my word of honour it has not been written up for the occasion” he assured the Committee.

The cash book entries also forced him to admit that the Hibs players had been paid, not only for time lost from work, but also for practice matches. Now proceedings took a comic turn. McFadden’s evidence was followed immediately by that from the player Groves who had clearly been told, in the best Baldric from Blackadder Goes Forth fashion, to deny everything. Obviously McFadden did not have time to update Groves that he, McFadden, had had to admit that certain payments had been made to players, including Groves. So Groves tells the Committee that he had received no payments whatsoever from anyone at Hibs for anything at any time, in flat contradiction to McFadden. Needless to say, he couldn’t explain why McFadden had just said the exact opposite.

That should have been game up for Hibs, but this, after all, is the SFA that we are dealing with, so consistency and common sense can’t be counted on. This second meeting was held on Thursday February 10th and the final was due to be played on Saturday 12th i.e. in two days time. This was a situation which the SFA had allowed itself to be manoeuvred into by Hibs. The difficulties of throwing Hibs out of the Cup were bad enough, but to delay the Cup Final was probably the key consideration for the Committee chairman, who was very much an SFA man. When the meeting voted on whether or not the Vale had proved its case, the Committee members divided equally. After a wrangle about a secret vote, the meeting voted again, but it was tied again. The chairman used his casting voted to side with Hibs, saying they had had a narrow escape. It was a disgrace, of course, all the more galling for the Vale because of their experiences 13 years before in the John Ferguson Affair. McFadden claimed that Hibs had been exonerated and asked the Vale to withdraw their accusations. The Vale replied that Hibs had not been exonerated, certainly not to the public at large and particularly not to the Vale. The Vale never withdrew its accusation and the public at large mostly agreed and sympathised with them.

Hibs subsequent win in the cup final against Dumbarton two days later was widely viewed as tainted, but that was little consolation to the Vale. There was one indirect result of Hibs victory and this was altogether more positive. At the Hibs celebration dinner after their Cup Final win, McFadden told some of Hibs’ Glasgow well-wishers that Glasgow should form its own Irish football club. One of the attendees was Brother Walfrid and he was taken with the idea since he was looking for some way to help the poor of the east end of Glasgow, many of whom, but by no means all, were Irish immigrants. His vision, however, was far more expansive and inclusive than the Hibs model at the time. The Football Club which Brother Walfrid formed in Glasgow’s east end was to embrace both Scots and Irish supporters and players, on the basis that both Scots and Irish were Celts. That was reflected in the original pronunciation of the football club which had a hard “C” at the beginning i.e. “Keltic”. Almost from the outset, Celtic had of course a Renton connection: the great Renton centre half James Kelly and the Renton forward Neil McCallum went to play for them in the spring of 1888. So if the Vale had forced Hibs’ expulsion, Celtic would not have been founded when they were and perhaps not on the basis on which they were either.

The final word on the affair no doubt gave some grim satisfaction in the Vale. As Billy McNeil, one of the finest players and gentlemen ever to grace the Scottish game, is fond of saying “time wounds all heels”, and in this case, time acted pretty quickly. Within a few weeks of the SFA Committee’s decision, Mr McFadden whose “word of honour” the Committee had accepted in preference to the more obvious truth of the Vale evidence, fled to Canada with Hibernian’s funds, swollen of course by the Cup Final takings, and money belonging to the Archdiocese of Edinburgh. He was never heard of again. You can imagine the “we told you so” coming out of the Vale and hopefully a few red faces in the SFA when news of McFadden’s theft came out.

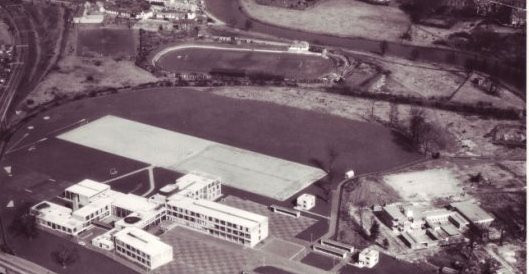

1888 – A new home at Millburn

The team was still performing reasonably well, and although the Vale were regularly losing at least one of their better players every season to the ranks of the professionals in northern England, and although crowds were down, the Club Committee felt confident enough about the future to look for a new home. North Street Park had served the Club well as the base of the “Old Vale Team” and was the scene of their great cup runs and victories from 1877-79. However, it was stuck between the gasworks, the railway line and the foundry, hardly the most salubrious location. The Park was no longer in keeping with the Vale’s status in Scottish football, especially in comparison with the new parks being built by their closest rivals, Queen’s Park and Rangers. The late 1880’s and early 1890’s was a period of great stadium building and ground upgrading. The Vale Committee probably felt a need to keep up with their rivals. In early 1888 the opportunity to match these new Glasgow grounds and to move to a much larger and more attractive site arose when the Turnbull family, who owned the Pyroligneous Works and lived in Place of Bonhill House, offered them a long lease of what had been known as Turnbull’s Park, at a peppercorn rent. It was too good an offer to refuse, and the Vale started to plan for the move.

The North Street Park era ended on an uncharacteristically down-beat note which must have made the departure easier. The very last game there was a 5-0 defeat to the great Renton team which just a month or so before had won not just the Scottish Cup but also the “Championship of the World”. The building work at Millburn began in May 1888, and the Vale played their first game there on Saturday 18th August 1888 - against Dumbarton, which ended in a 2-2 draw.

Contrast the building speeds and costs of 1888 with to-day’s performances. Construction of Millburn began on 25th May 1888.on a 12-acre site - 5 acres were allocated to football at that time - on the same plan as the then Hampden Park. (This was the second ground of that name, which Queen’s Park occupied from 1884 – 1903. It was then acquired by Third Lanark and renamed New Cathkin Park which Thirds occupied until their demise in 1967). This meant a park 120 yards long by 75 yards wide, with a surrounding quarter mile cinder track 15 feet wide, with a final stretch on the eastern side of 20 feet width.

The preparation and laying out of the pitch and track cost £442, and this involved levelling what had been up until then a hilly site, although that’s hard to envisage now. The pitch and turf contractor was a Thomas Kinloch of Alexandria while Graham & McLaren, joiners of bank st Alexandria carried out other work such as the dismantling and re-assembly of the pavilion and stand. The surrounding fence was from the outset made of corrugated iron sheets (“like Ibrox” as was noted at the time) and this together with moving the grandstand and pavilion from the North Street Park brought the total cost to about £700. The brand new Millburn Park was ready for the first game on 25th August 1888 - just under three months from the start of the work to the first ball being kicked. Perhaps the owners of the Edinburgh tram fiasco should see if Mr Kinloch is contactable, wherever he is now.

Millburn and adjacent football pitches in the 1960’s.

Note the intact covered enclosure, complete terracing and pavilion

Naturally, the official opening of the ground with that first match against Dumbarton was a grand affair, attended by the great and good not just of the Vale but also of Scottish football. The ground was declared open by Mr William Ewing Gilmour, one of the Vale’s leading benefactors of the late 19th century – e.g. he paid for the Gilmour Institute and what is now the Masonic Temple. He was a keen sportsman who was also President of the Vale FC and it gave him great personal pleasure to walk out to the centre spot and get the game under way by kicking the ball up into the air. The Millburn show was on the road.

Perhaps the size of the crowd of 3,000 for such an auspicious occasion in a local derby should have served as a warning signal of trouble ahead. While it was a good enough crowd, it was not as good as the occasion perhaps deserved. It was too late, anyway, because the Club, which never before had debts of more than a few pounds and these could be cleared by a couple of games in England, was now burdened with a debt of the about £750. This debt was to dominate the Vale’s affairs for years to come and the Club never escaped the problems it caused in the Vale’s remaining years as one of Scotland’s top-flight clubs. Just like to-days heavily indebted clubs it was clear evidence of ambition being unmatched by reality. On the other hand, it is probably also fair to say that the sense of responsibility and duty to repay the debt kept the Club going through the very difficult years which lay immediately ahead, when many people just wanted to close it down.

The ground has survived remarkably well over the years: the pitch itself and its immediate surroundings haven’t changed much at all. The pitch remains one of the best playing surfaces in the country. A new brick bungalow type pavilion was built early in the 20th century and lasted with some alterations for many years, until destroyed by arson, as was the fate of a large wooden shed, which housed the Vale of Leven Harriers who shared Millburn with the Vale until the 1970's. A new Fort Apache-type clubhouse now houses changing and committee rooms etc, but vandalism has recently damaged the turnstile area. A covered enclosure was added on the west terracing in the early 1900’s and was also altered and updated, again incurring debt. You’d have thought that the club might have learned its lesson from the debt of 1888, but no, and the enclosure debt was a major problem throughout the 1920’s. A new covered enclosure to accommodate 1,200 people was completed in 1954, but the Scottish Junior Cup win helped to pay for that. This enclosure was reduced in size by a storm about 25 years ago, when the northern shed was blown away. This left the Vale with the unique distinction of having both a winter and a summer stand - the winter one covered against the elements, the summer one a steel-frame skeleton in which to sunbathe while watching the game – after all the sun always shines at Millburn. The Millburn Trust has owned Millburn Park since 1946.

The early years at Millburn

The Vale’s continuing high profile in Scottish football was demonstrated in November 1888 when the team was invited to take part in a match against Rangers as part of the Glasgow International Exhibition of that year. The Exhibition was held at Kelvingrove on a site now largely occupied by Kelvingrove Museum and Art Galleries. An Exhibition Sports Ground had been laid out just across the Kelvin from the Exhibition site on land long since occupied by University and Western Infirmary buildings.

It was a floodlit match and you would have thought a Glasgow November night was perhaps less than ideal to trial what was a new type of floodlights. You would have been right. However, the Vale were already pioneers in playing under floodlights. In October 1878 they had played Third Lanark under electric lights at the first Cathkin Park, in the very first floodlit game to be played in Scotland. Apparently this game was played with the use of a single spotlight which followed the ball in the way a spotlight follows an actor about the stage. Even allowing for the fact that some reflecting equipment did not arrive from the continent in time for the match, this type of floodlighting was unlikely ever to catch on. So there were high hopes ten years later when a new system called “Well’s Light” was being tried out, and it was under this system that Rangers and the Vale played as part of the Glasgow Exhibition. Although this floodlighting was an improvement, it was not a success and floodlights had to wait another 60 years before being widely used in Scotland. (Anyone who was a regular at Boghead from the 1950’s to the day it closed may well suspect that the Well’s Light system had been kept in a cupboard there for 70 years in readiness for a gloomy reappearance at the venerable Dumbarton stadium.)

It was also in November 1888 that the Vale played Celtic for the first time. The game was played at Millburn and this was the biggest crowd so far to attend the new ground. Celtic ran out 2-1 winners, one of their goals being scored by Neilly McCallum, a recent Celtic recruit from Renton. Neil had been born in Bonhill overlooking what was to become Millburn, and is buried within a few yards of Millburn just across the Leven in Bonhill Churchyard.

Season 1889 – 90 was a highly significant year not just for the Vale, but for the whole of Scottish football. It was the last season in which the Vale appeared in a Scottish Cup Final and it was the season in which the Scottish League was formed, although it did not start to operate until the next season, 1890-91. The Vale’s last hurrah in the Scottish Cup came in the final in 1890. After a 1-1 draw with Queen’s Park in the first game, in which the Vale lead until the last minute, Queen’s went on to lift the Cup by beating the Vale 2 -1 in the replay. The games were both played at Ibrox before crowds of 10,000 and 14,000 respectively. Vale’s share of the gate money of £300 was very welcome in reducing the debt.

Although it is perfectly true that this was the end of an era for the Vale, and that they never again progressed far in the Cup, it’s often overlooked that this was also the beginning of the end of an era for Queen’s Park. After this victory over the Vale in 1890, Queen’s only won the cup once more themselves, in 1892-93 when they beat Celtic 2-1 in a replay after a 0-0 draw, and were beaten finalist on only two other occasions – in 1891-92 when Celtic beat them 5-1, and 1899 – 1900 when Celtic again beat them this time by a more respectable 4-3. The 1890’s saw the end of competitive small-town and amateur clubs – the 20th century belonged to the big professional clubs from the big towns and cities, just as the 21st century is seeming to belong to the mega-rich clubs fed by TV revenues and / or the vanity of owners with more billions to waste than sense. The blame for the decline in the smaller Scottish teams in the late 19th century is often put down to the formation of the Scottish League, but that reason alone does not survive closer examination.

Next - Formation of the Scottish Football League in 1890 >