Sir John Pender, Entrepreneur

Sir John Pender was a Bonhill lad who went on to find fame and a considerable fortune as an archetypal Victorian entrepreneur, who thought in terms of solutions rather than problems, and whose greatest successes came in the earliest stages of a field which remains central to the way we live to-day –  telecommunications. Sir John did not invent any of the technology involved in the field of his greatest success - submarine cable telegraphy - but he recognised its importance and value better than just about anyone else and risked considerable amounts of his own money to bring about the world-wide submarine cabling system on which modern telecommunication still depends.

telecommunications. Sir John did not invent any of the technology involved in the field of his greatest success - submarine cable telegraphy - but he recognised its importance and value better than just about anyone else and risked considerable amounts of his own money to bring about the world-wide submarine cabling system on which modern telecommunication still depends.

Most Vale people to-day have never heard of John Pender. Local history is rarely discussed in the school system, and the last local history book to mention him was John Neil’s “Records and Reminiscences of Bonhill Parish”, and that was written in 1912. As ever Wikipedia fills a gap, and there are biographies and histories from earlier times in which Sir John figures prominently. We are fortunate to have received much of the information on which this short biography is based, and the article from the Zodiac, from a descendant of the Bonhill Penders, Sheila Dawes.

As Sheila says “John Pender was Bonhill born and bred and went on to dominate the world-wide use of submarine cables for telegraphic communication. My great grandmother on my father’s side was a Pender and appears to have been a cousin of Sir John. The whole family seem to have been bleachers and involved with the textile industry. My immediate family moved to Strathblane and it is well recorded that many in the Vale textile industry moved to the foot of the Campsies. In later years, this migration spawned a Vale phrase recorded in Ferguson & Temple’s “The Old Vale & Its Memories” of 1927, that “if ye’re born in the Vale an’ brocht up in Campsie, ye are fit for onything””.

John Pender was born in Bonhill on 10 September 1816 to James Pender and Marion Mason. He may have gone to school in Glasgow, which would have been quite exceptional for the time, but after leaving school he started work as a pattern maker for Gilbert & Lang & Co at the “Wee Field”. This printworks was squeezed in between Bonhill Parish Church and the Burn, on the banks of the Leven. It opened about 1793, but was closed and demolished by 1840. John Pender had left the Wee Field some time before this to go and work in Glasgow, still in the textile industry. Being a pattern-maker at a printworks was an important position and John would have become well versed in the textile industry while at the Wee Field. On 21 November 1840 he married Marion Cairns in Bonhill, but that was a tragically short marriage because Marion died in September of the following year giving birth to their son, James.

John Pender then moved again, firstly to Manchester and eventually to London. In Manchester he put his knowledge of textiles to good use and became a successful and affluent textile merchant, in what was at that time the world capital for finished cotton goods. He also married again in 1851, to Emma Denison, by whom he had two daughters (who in 1864 were painted by a leading artist of the time, Millais; the portrait now hangs in the Detroit Institute of Arts) and a further two sons. Never a man with a single track mind, Pender looked around for other business opportunities, and found them with an investment in a submarine telegraph cable across the Atlantic.

Unlike many of the other 340 people who invested in the Atlantic Telegraph Company and its first doomed telegraph cable link between Britain and North America, Pender well understood the potential benefits from such an improvement in communications. After all, most of the raw cotton in which he dealt came from the southern states of the US, and he was in frequent correspondence with agents and growers in the US.

The first link was laid in 1858 and the cable ran from Valentia on the west coast of Ireland to Newfoundland - a distance of 1,660 nautical miles. The cable-laying operation was a success, but unfortunately the technical problems of long-distance transmission were not properly understood. The first working submarine cable in the world was laid in 1851 connecting Dover and Calais, a distance of a little over 21 miles. There seemed to be a perception that increasing that distance nearly 100 times would not present any insuperable problems. In fact, the scale of the increase in the problems of maintaining a signal across the Atlantic from that of sending signals across the English Channel was at the edge of scientific understanding at the time. To make matters worse, the company’s technical expert ignored the scepticism of his main advisor, Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, about the solution that the company adopted to solve the transmission problems. The solution of turning up the voltage actually damaged the cable so much that after only three months and as few as 732 very poorly transmitted signals, the cable went dead, never to be heard from again. It is still out there somewhere.

The investors lost most of their money, and underwater cables were definitely not the flavour of the month. In fact, it took 7 years before a second attempt was made in 1865 to lay another cable, using Brunel’s ship the SS Great Eastern as the cable-laying ship. It was the largest ship in the world at the time, and its size was necessary given the dimensions of the new cable. This time Pender had increased his investment, and also he was part owner with Gooch and Thomas Brassey, Pender’s equivalent in the railway building industry, of the Great Eastern. The effort was almost biblical in scale with a crew of 500, 200 of whom were needed just to raise the anchor. 12 oxen were on board to help lay the cable, as well as a small farm of pigs for food and a cow for fresh milk. The problem this time was that they lost the cable after 1,186 nautical miles and, despite repeated grappling, failed to find it – the water was 2 miles deep at this point. The attempt was abandoned.

Pender still firmly believed that the telegraph cable link was the way of the future. He also understood the value of the technical improvements which had been made both to the cable itself, and to the transmission techniques. Amongst others, Sir William Thomson had been working away at solutions to these problems, both in his laboratory at Glasgow University and at sea where he conducted a number of practical trials. His able assistant in all of this was another Bonhill man, Donald McFarlane.

In 1866, it was decided to try a third time, but the existing company, Atlantic Telegraph ran into legal problems, so Pender and his partner Gooch founded their own company, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, to take over the project. By this stage investors were in short supply and banks were very reluctant to lend them anything. Undaunted, Pender and Gooch put up their own money as guarantees, about £250,000 each - pick any very large number you like for a modern equivalent. They again used the Great Eastern. Onto it they loaded 9,000 tons of a newly-designed cable which was 3 times the diameter of the earlier ones, and which also addressed the sheaving problem encountered with the 1865 cable. Sir William Thomson’s research had also solved many of the transmission problems by this stage.

Off they sailed into the sunset, accompanied by a small flotilla of guard ships and helpers. Assisted by good weather, in a truly astonishing two week period of cable-laying, they reached their target destination, the appropriately named Heart’s Content in Newfoundland. Within a day or so, Queen Victoria and President Andrew Johnson of the USA exchanged the first message over the new cable, on July 29th 1866.

But perhaps their greatest achievement of that cable-laying season lay just ahead. A few days after their first successful transmissions over the new cable, the Great Eastern tracked back eastwards to recover the lost cable from 1865, which it did after 30 grappling attempts. The crew promptly spliced it and then sailed back again to Heart’s Content with a second complete Transatlantic cable. By 9th September 1866, Pender was therefore the proud owner with his partner Gooch of not one, but two working Atlantic cables. There’s hardly a better example of the Victorian indomitable will to win.

That was just the beginning of a cable business empire which he created, which connected all of the corners of the British Empire and beyond. While the British government took all inland cable companies into its ownership between 1868 and 1870, it left overseas communications to the private sector. Pender made the overseas telegraph cable business virtually his own private domain. Companies owned by Pender laid cable from Britain (Porthcurno) to India (1869 -70), and Gibraltar and Malta (1870), China via Singapore and Hong Kong, Adelaide in Australia to Bombay (1872) and in 1874 he branched out to Brazil from Lisbon. Within 15 years 30,000 miles of cable had been laid to 64 stations across the world linking Australia, South Africa, China and South America to Britain. His vision was world-wide, his energy relentless and his approach was to succeed – which he did in aces.

He bought key supply companies such as the cable makers. At one time he owned over 30 cable companies, and he only reduced that number by re-organisation into fewer, larger units, not by disposal. Some companies still operating to-day or in the very recent past were originally created by Pender, Cable & Wireless (which was a straight re-name in 1934 to shed imperial connections of a company founded by Pender) being the most obvious, but also the BICC cable company.

In parallel with his business successes, he also maintained a political career for over 30 years. As any Bonhill man of his generation would have done, he set out as a Liberal. In his formative years the whole of the Vale was radical, strongly supporting the Chartist agitation of the 1830’s and 40’s for political and economic reform. Indeed it was said at that time that there was hardly a Tory in Bonhill.

In 1862, at the age of 48, Pender entered Parliament by being elected to the seat of Totnes in Devon as a Liberal. Although the 1832 First Reform Act had swept away most of the rotten boroughs, a few remained, and one of them was Totnes. True, it was not as bad as some earlier rotten boroughs, in that it actually existed, and had neither fallen into the sea nor been deserted by its inhabitants, but its electorate was drawn exclusively from the 2,000 or so people who lived in the small town of Totnes. Although there seems to have been an element of party politics involved when a Tory government disenfranchised it in 1866, the Liberals could hardly complain since they were in agreement with the objective of abolishing borough constituencies with populations of less 10,000. If John Pender was disappointed about being ejected in this way from Parliament, he at least had his stunning transatlantic cable success to console him, to say nothing of the prospect of the riches beyond the dreams of avarice to come.

Something about Parliament must have attracted him, because in 1872 he was elected, again as a Liberal, to an even farther-flung constituency, Wick, or Northern Burghs. On the face of it, you’ve got to wonder why on earth such a busy and successful man would chose to represent the constituency which is second-furthest from Westminster. Try as you might, which will not be at all hard, you will not find the answer in his interventions and contributions in the chamber. In the 20 years in which he was a Member of Parliament, he made a grand total of just 10 contributions – about one every two years. True, one of them about the Royal Mail deliveries via the new railway to Wick could almost be used verbatim as a Monty Python sketch, but the other interventions could be construed as motivated by self-interest or straight lobby fodder.

Equally true, these were very different times in Parliament. Parliamentary sessions were much shorter than to-day, MP’s were not paid, MP’s often did not live in their constituencies and some did not even visit them at all between elections. The electorate was still very small in comparison to what it became, and by and large people’s expectations of their MPs at that time were very limited.

However, things were changing in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland in the 1880’s and that change seemed to go unnoticed by Pender, or perhaps more likely, he did not agree with the direction events were taking. The crofters and cottars of the north had been victims of clearances and absentee landlords for about a century, and by the 1880’s they had had enough. They took direct action against the landowners in what became known as the Crofters War. Land was settled by the locals, the landlord’s sheep and cattle were driven off, deer parks and forests were invaded, factors and even a few landlords were no doubt intimidated. The whole issue has political resonance even to-day in Scotland, but at the time it was active civil disobedience on a scale which had not been seen since the 1745 Uprising, and it brought out the UK governments’ customary colonial reaction of sending in gunboats and troops to put down the natives.

It is hard to imagine a more clear-cut issue for a Liberal – the people on one side and the landowning classes led by the likes of the notorious Dukes of Sutherland and Argyll on the other. If Pender retained any of his early radicalism he hid it well, and the voters of Wick Burghs recognised this. In 1885 at the height of the Crofters War he lost his seat of Wick Burghs to a Highlander, John MacDonald Cameron, who was standing as a Crofter-Liberal candidate. What makes Pender’s judgement at the time seem even worse, was that as well as being on the wrong side of the argument, he was also on the losing side – the crofters actually got most of what they wanted.

While Pender was out of Parliament, he left the Liberal Party to join a new grouping of former Liberals, the Liberal Unionists. To begin with, most Liberal Unionists left the Liberals over Gladstone’s attempts to introduce Irish Home Rule - the Unionist element was Union with Ireland and not Scotland, which was not in question at that time. In reality, the Liberals had always had a socially and economically conservative wing of aristocratic and moneyed people whom one would have expected to find in the Conservative Party, but who believed in a measure of social and political reform. By the 1880’s most of them thought their reform goals had been achieved and they could give up any pretence of being Liberal or even, in most cases, liberal. The Liberal Unionists were Conservatives in Parliament. However, the Conservatives were unpopular in Scotland, and in the 1880’s the title Conservative was abandoned in Scotland, not to be used again until 1965. It was believed by the Tories, quite correctly as it turned out, that they stood a far better chance of being elected if they had the term “Liberal” in their title, so they usually stood as Liberal Unionists.

Pender threw in his lot with the new Liberal Unionists and had his first run out in his new political colours at Govan in 1886, but failed to get elected. He was knighted in 1888, so that when he stood again for Wick Burghs in 1892, he stood as Sir John Pender, Liberal Unionist. He was once more elected at the age of 75 and was still an MP when he died aged 79 in 1896.

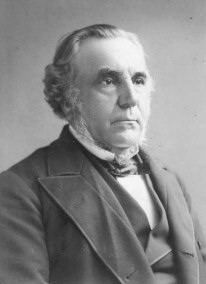

Sir John Pender’s story is one of classic Victorian achievement, by his own efforts. The trappings of success accompanied his achievements. His portrait, first published in Vanity Fair in 1887, now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London, along with another painting entitled "Private view of an Old Masters exhibition Royal Academy 1888" in which he appears in the company of the great and good of the day, including William Gladstone. He is certainly the only Valeman to appear in the National Gallery; to appear twice has all the hallmarks of a Bonhill man. And he retained his Bonhill friendships. According to John Neill, Sir John was in contact for many years with old friends in Bonhill, paying their rents and sending gifts at Christmas.

An article in "The Zodiac" in 1922 sums up Sir John thus "The story of John Pender's inexhaustible tenacity and courage, and his enduring faith, in the face of recurring adversity, is an inspiration to all: and, it is typical of the finest British instincts."

Sir John died in July 1896 and is buried in Foots Cray, Bexley, south-east London.