The Vale of Leven's Famous Industrial People

Sir William Bilsland | The Ewings | The “Ewings of the Lands of Balloch”

John Orr Ewing of Levenfield | Sir Archibald Orr Ewing

William Ewing Gilmour | The Ewings of Strathleven

James Ewing of Strathleven | Humphry Ewing Crum-Ewing of Strathleven | Alexander Crum Ewing | Humphry Crum Ewing

Although not a Valeman in the strictest sense, Sir William Bilsland had very strong Vale connections, and the Vale played a part in shaping him. He was born on St Patrick’s Day in 1847 at Ballatt, into a family whose members had been farmers for centuries in the adjoining parish of Kilmaronock – and indeed still are. It was members of the same Bilsland family who farmed at Mid Auchincarroch farm for over a century, until about 1980.

At an early age he was sent to school at the best school in the area, which at that time was Dalmonach School at Bonhill. While attending the school he lived in the Vale with his uncle, Dr Alexander Leckie. At the age of 13 he became an apprentice grocer in Glasgow and at the age of only 22 he bought his own grocers shop in 1869. In 1872 he branched out into a bakery when he saw the potential of supplying bread to the fast growing industrial centre of Clydeside, founding Bilsland Brothers which traded as Bilsland’s Bread. He later also acquired a controlling interest in Gray Dunn's biscuit company.

Bilsland was elected a Glasgow town councillor at a time of great civic pride and aspiration in the city. He was prominent amongst the group of civic leaders who led the way in establishing Glasgow’s reputation and leadership – which it has retained to this day - in cultural affairs such as museums, art galleries etc. Free Libraries were a cause particularly close to his heart and Bilsland was a driving force in getting them established across the city. Again, Glasgow’s reputation, which is based not just on the library network, but also on the fine buildings in which they are housed, has endured. Robert Bilsland was elected Lord Provost from 1905 – 1908 and thereafter joined the ranks of the great and the good, gathering many a decoration, including a knighthood, along the way. He died in 1921.

Perhaps the last public reminder of Bilsland’s Bread survives in the Anderston Area of Glasgow – the red-brick building which was the bakery and company head-quarters, which still stands just to the north of the Kingston Bridge. It still carries a fading but quite distinct sign “Bilsland’s Bread” which can be read when crossing from south to north on the bridge – by passengers only of course.

<top>

For much of the 19th and part of the 20th century there were two quite separate prominent Ewing families in the Vale of Leven. One was the Orr Ewings, which owned many of the textile finishing factories in the Vale. The other one was the Ewings of Strathleven, later the Crum-Ewings, which made most of its initial fortune out of its West Indies sugar plantations, which, until the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, were worked mainly by slaves. James Ewing, the founder of the fortune, was a slave owner.

Strangely enough, both families arrived in the area in 1835 although, certainly in the case of the Orr Ewings, they were definitely connected to the earlier “Ewings of the Lands of Balloch”. The Ewings or Crum Ewings of Strathleven were a bit more complicated. Adding a name to inherit money or property was a well recognised Victorian practice and the family to which the Strathleven Ewings belonged raised it to something of an art form in the 19th century. The Crum Ewings were also connected to the Dennistoun Browns, the last private owners of Balloch Castle and Estate, who sold both to Glasgow Corporation in 1915.

All have long since departed the area. The last of the Orr Ewing branch to live in the Vale was William Ewing Gilmour, who gave up residence at Woodbank in 1921, while the last Crum Ewing connection was severed within a year of Humphry Crum Ewing’s death in Jamaica in November 1946.

<top>

The “Ewings of the Lands of Balloch”

The Ewing family is sometimes referred to in older history books and newspapers (particularly the obituaries of the Orr-Ewings) as an old family from “the lands of Balloch.” These days this comes as a surprise to most people from Balloch and the Vale. What’s perhaps even more surprising is that the claim is pretty well spot on. There is a record of an Alexander Ewing being born at Balloch around 1660. Only 60 years later the evidence firms up and in 1724 Robert Ewing was born at Balloch. He went on to inherit Ledrish (now Ledrishmore) and Ledrishbeg farms from his father. This Robert was the grandfather of John and Archibald Orr Ewing, who, of course, founded the great textile companies in the Vale which were to carry both of their names and which eventually became part of the UTR. He was also the great-grandfather of William Ewing Gilmour, a noted Vale benefactor who was not only a director of the UTR, but also paid for the building of two of the Vale’s finest surviving buildings, the Gilmour Institute and what is now the Masonic Temple.

Robert Ewing’s son, William Ewing of Ardvullin near Dunoon (John and Archibald’s father), married a Susan Orr. It was from her that the name “Orr” appeared, which was added to the Ewing by both John and Archibald, although it is said that Archibald only added it in 1845 when he started up in business for himself, at the behest of his brother John. William Ewing’s elder daughter Isabella married Allan Gilmour, a very rich farmer, land-owner, and timber merchant, who inherited not one but two estates at Eaglesham. Isabella Ewing and Allan Gilmour’s son was William Ewing Gilmour, who eventually joined his uncle John in the John Ewing Company of Croftengea and Levenfield. As has been mentioned, William Ewing Gilmour, with his wife, was to become a major benefactor to the Vale from the 1880’s until the 1920’s. William was the last of the major players in this Ewing family to live in the Vale – at Woodbank House – and although he moved permanently to Sutherland in 1921, when he died in 1924 he was buried in Alexandria cemetery.

Although William Ewing Gilmour had Gilmour Street named after him, and although the first of the Jamestown Terraces, now demolished, was called Ewing Terrace, the name Ewing has not survived in any Vale place-name. Being mentioned in the dedication of the Gilmour Institute hardly seems to make up for that.

<top>

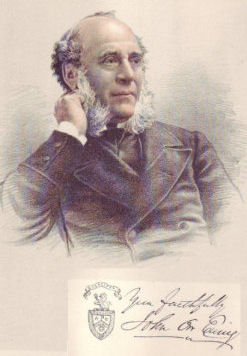

John Orr Ewing was the second son of William Ewing of Ardvullin, Dunoon, mentioned above. Although his younger brother Archibald went on to great public prominence in the Vale and beyond, it was John Orr Ewing who led the Ewing family back to the Vale and into the textile finishing industry in which it made a great deal of money. Indeed some of them are still living off of the proceeds, so they have a lot to thank him for.

John Orr Ewing was the second son of William Ewing of Ardvullin, Dunoon, mentioned above. Although his younger brother Archibald went on to great public prominence in the Vale and beyond, it was John Orr Ewing who led the Ewing family back to the Vale and into the textile finishing industry in which it made a great deal of money. Indeed some of them are still living off of the proceeds, so they have a lot to thank him for.

He was born in 1809 and began his business career in Glasgow about 1828, soon moving into the textile industry. At this stage and for another 7 years or so, he had no business interests in the Vale at all, but in 1835 he and a partner, Robert Alexander, spotted a possible opportunity and leased the Croftengea Works. This marked the return of the Ewings to the area, and the beginning of a career which must have at least met his best youthful aspirations. He launched the new venture as John Orr Ewing and Company, bleachers and Turkey red dyers, and from the start it was a considerable success. In 10 years of steady expansion John Orr Ewing & Co grew in output, profit, employees and status within the textile finishing industry.

Having built the business up and having made a lot of money in these 10 years, in 1845 he and his partner, Robert Alexander, both retired and although the company was renamed Robert Alexander and Co, it was under the control of two in-comers, John Clark and James Barnet. John went off to Ratho on the outskirts of Edinburgh to lead the life of a country gentleman on his newly-acquired estate. At the same time his younger brother Archibald left John Orr Ewing & Co to start up on his own just across the river. It is said that at this time John prevailed upon Archibald to add the “Orr” to his name, and that John helped his brother financially and in other ways in starting up his new venture. Presciently, as it turned out, John retained personal ownership of some of the factory buildings at Croftengea.

Orr Ewing’s success in business was noted by his contemporaries and he was in demand as a director of other companies. From its formation, he was a director of the company which was set up to bring the railway into the Vale, the Caledonian & Dumbartonshire Railway. This was a mutually beneficial move for Orr Ewing and the Railway Company. Hopefully his name would attract other investors to the Railway (not enough to begin with, as it turned out, because there were insufficient funds to take the line all the way to Glasgow and for a time it terminated at Bowling Harbour station). It also no doubt brought business benefits to John Orr Ewing & Co as a major customer of the railway. His stint as a director of the local railway led to him becoming a director of the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway, which owned Queen Street station. These railway directorships allowed him to keep in touch with the business world during his years of temporary retirement.

Arguably his major business role outside of the Vale was as chairman of Young’s Paraffin Oil Company, then one of Britain’s leading companies. It was a dominant party in the emerging fuel oil industry in the UK. Founded in West Lothian by a Glasgow man, James “Paraffin” Young, Young’s Paraffin Oil Company was the foundation organization of what to become British Petroleum. Although both Young and his company are almost completely forgotten now, for the second half of the 19th century James Young was one of Britain’s best known and successful entrepreneurs. The use of oil as a source of energy was in its infancy, with no oil wells as such in existence anywhere. Most fuel oil was paraffin, extracted from cannel coal, but that source soon ran out. Young devised a process to extract it from shale, of which there was an abundance in West Lothian. Shale mines were dug and shale extracted, and Britain’s first oil refinery was set up in Bathgate before a much larger one was opened at Addiewell, West Lothian where Young also headquartered the business. The red coloured pit bings are still a prominent feature of the landscape beside the M8. That Orr Ewing should be invited to be this Company’s chairman is eloquent testimony to regard in which he was held by his business contemporaries.

Back in the Vale, the one positive thing which the new owners of what had been John Orr Ewing & Co did, was to buy Levenfield Works in 1850 from John Todd, whose family had started it in 1788. However, by 1860, Robert Alexander & Co was a failing business. John Orr Ewing was summoned from retirement to halt the downward spiral of the business which he had created, and in the success of which he retained an interest, not least through the ownership of the Croftengea buildings. At the age of 51 he resumed control and this time he did not relinquish it until his death. The first thing he did was to re-instate the company’s name of John Orr Ewing & Co, which it stayed until being incorporated into the new company of the UTR in 1897.

What he found was that production levels were where he had left them 15 years previously. Perhaps taking his younger brother’s success as an example, he greatly expanded the business and that was reflected in the growth of Levenfield and Croftengea into the huge site which became known as Alexandria Works, or more commonly to Vale folk, the “Craft”.

A notable feature of his second spell in charge was his development of a team of very able young men as the future generation of managers – he was not about to repeat the experience of seeing his efforts frittered away by poor management. These included John Christie, who had joined as a chemist in 1856 (the first qualified chemist in the Vale it is said) before John Orr Ewing resumed control and went on to be general manager, senior partner and first chairman of the newly-created UTR. Another was John Orr Ewing’s young nephew, William Ewing Gilmour, who joined the firm in 1874 and went on to be the UTR’s chairman after John Christie.

John Orr Ewing lived at Levenfield in his later years, and in that sense he was very much part of the community, but not really in any other. He was not a noted benefactor of the Vale or anywhere else. Although his company came to own many houses in Alexander and India Streets and elsewhere close to the Works, he had no terrace building program to compare with his brother. He also left public politics to his brother. His recreational pursuits were those of a country gentleman rather than an urban industrialist – of the hunting, shooting and fishing variety. Apart from the Works he left no mark on the Vale, unlike other members of his family.

In 1878 he was not feeling very well, and as rich Britons did in those days, he went to the newly-popular French Riviera for his health. He wasn’t in Cannes for more than a few weeks when he died, so his last major decision – to get a rest in the sun - was certainly the right one. He had married in 1840, but the couple had no children to inherit the fortune of £460,000 (perhaps £30+ million in to-days values). Mrs John Orr Ewing vacated Levenfield and went to live at Ardardan, Cardross.

<top>

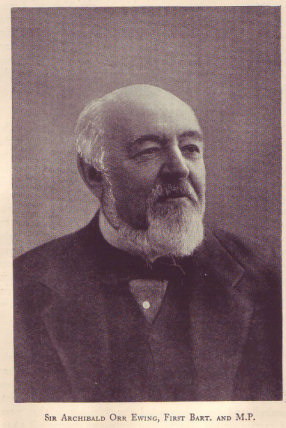

Born as Archibald Ewing in 1819, he died on 28th November 1893. Archibald was the fourth son of William Ewing and Susan Orr, and the younger brother of John Orr Ewing of Croftengea, and Levenfield, for whom there is a separate entry. John first leased Croftengea Works in 1835, and turned it into a great success. To begin with, Archibald worked there for his older brother, but left when John retired for the first time in 1845 (John bought the business back in 1860).

Born as Archibald Ewing in 1819, he died on 28th November 1893. Archibald was the fourth son of William Ewing and Susan Orr, and the younger brother of John Orr Ewing of Croftengea, and Levenfield, for whom there is a separate entry. John first leased Croftengea Works in 1835, and turned it into a great success. To begin with, Archibald worked there for his older brother, but left when John retired for the first time in 1845 (John bought the business back in 1860).

On leaving the Croft, Archibald went into business on his own account, helped by John. He called the business Archibald Orr Ewing & Company, the name it retained until it merged into the newly-formed UTR in 1897. He also added the “Orr” to his own name at this time. This may have been out of family loyalty, but it may also have been an astute business move to capitalize on the well established “Orr Ewing” company name. Either way he became known to one and all as Mr Archibald Orr Ewing.

Archibald’s first solo venture was to buy Levenbank Works in Jamestown in 1845, which he quickly set about expanding. In 1850 he added Milton Works, which at that time were wedged between the main road and the Leven, just across the river from Croftengea. He quickly expanded them, too, onto the ground now occupied by Gilmour & Aitken, and built a tunnel (now bricked up) to carry a railway siding into the riverside part of the works. Finally, he added Dillichip Works in 1866, and in the process of expanding that he acquired the defunct Kirkland Works which lay just to the north of Dillichip, and cleared that site. His personal industrial empire was now in place, on the east bank of the Leven. At its peak of production, his factories employed almost 2,000 people, and made a very great deal of money for Archibald Orr Ewing.

During most of the time he was building up his great industrial empire, Archibald lived in Lennoxbank House at Dalvait, Balloch. He acquired Lennoxbank as well as Levenbank Works from John Stewart or Stuart, who had built Lennoxbank in 1826, when he was already the owner of the nearby Levenbank Works. However, in 1862 Archibald commissioned the building of a grand Scottish baronial pile at the estate of Ballikinrain, which he had just bought (originally styled as being “near Killearn” but now its postal address is Balfron), in Stirlingshire. He left Lennoxbank House on Ballikinrain’s completion in 1862 and lived there for the rest of his life. At about the same time he bought the estate of Edenbellie which was close to Ballikinrain, and also the estate of Gollanfield between Inverness and Nairn.

That did not stop his acquisition of property in the Vale. His firm bought the lands of Mill of Haldane from James McAllister, Arthurston from John Ritchie, Mill of Balloch from Peter McAllister, and Kirkland from the trustees of Mathew Perston. His factories expanded onto some of this land, but some of it was used to build houses for his workers.

The Orr Ewing business interests were not restricted to the Vale. The large landed estates in Invernesshire and Stirlingshire have already been noted, but he also had substantial shareholdings in shipping, railways and other companies. He found time, too, to play a prominent role in Glasgow’s business affairs and took a leading role in promoting Glasgow University’s 1862 move from College Street to its present site at Gilmorehill, as well as being a substantial funder of that project.

As his factories continued to expand, the need for more employees also created a need for more and better housing for them. Orr Ewing rose to the challenge, building a number of terraced houses in Jamestown, Bonhill and Balloch. The best known of these were, of course, the Jamestown “Terraces” which were built between 1867 and 1874. But he also was responsible for the building of other well known buildings such as the Wimmin’s House and Dillichip Terrace in Bonhill, and Haldane Terrace at Mill of Haldane. While he made money from the rent of these houses, they were built to high standards for their time and some have survived very well.

Jamestown, in particular, benefited from a number of donations from Archibald Orr Ewing, which was quite appropriate since two of his factories were located there. He contributed to the building of a new Primary School (about 1856), the new Parish Church (1869) and the village hall (Arthurston Hall, which eventually became the Church Hall). His political self-interest also saw the building of the Conservative Party Rooms in Jamestown, on the south-west side of the level crossing at Jamestown Station. Both the school and the Church survive to this day.

Having made his mark in the textile industry, and continuing to rake in the money from the Vale factories, he turned his hand to politics. For 24 years, from 1868 until 1892, he represented the County seat of Dumbartonshire at Westminster as a Tory, rarely with a majority of any more than a few hundred votes. Given his proven abilities, and stripping away the fawning tributes from his local contemporaries, he seems to have been a competent enough back-bench MP. More competent, certainly, than his immediate predecessor, PB Smollett. But then, the statues in the parliamentary lobbies were more competent than Smollett, whose only claim to parliamentary fame was a speech in the House which earned the jibe of a fellow Tory MP, Benjamin Disraeli, who went on to become an outstanding Conservative Prime Minister, that the reason that no one knew what Smollett was talking about, was because he did not know himself. So he was hardly a hard act to follow, but Orr Ewing proved to be an able, typical Tory shire MP.

In 1886, he was made first Baronet Orr Ewing of Ballikinrain, which was, of course, in Stirlingshire and not the county he represented in Parliament and in which he had made his considerable fortune. For an MP, then as now, being knighted is a sign of time served without upsetting anyone in the Whips office, rather than a reward for outstanding achievement and it is perhaps a little surprising that he did not rise to greater things in Parliament. There were many industrialists of that time, however, in both the Liberal and Conservative parties, who were happy to have the status of being an MP without seeking further political advancement.

Nonetheless, he was an avid promoter of the Conservative cause, and was a founder of Glasgow & West of Scotland Newspaper Co, which published Conservative-supporting newspapers. It is worth noting that his investment in Jamestown Conservative Party Rooms proved far more durable than that in the Conservative newspapers. The Rooms long outlived the newspapers - as well as any measurable Conservative support in the area.

When Sir Archibald, as he was then, retired from politics in 1892, he left Parliament without having made a significant political mark. The Dumbartonshire seat was gained by the Liberals in the 1892 general election, so his small majorities arguably had an important personal element. He did not have long to enjoy his retirement, for he died the next year, 1893.

His descendants kept the family name prominent over the years. His son Charles, after whom Charles Terrace in Dalvait Road, Balloch, was named, was MP for Ayr from 1895 until his early death in 1903. Up until his death, Charles continued to live at Lennoxbank House, and he is almost certainly the first and, so far, last, Valeman to have news of his death carried on the front page of the New York Times newspaper.

His descendants kept the family name prominent over the years. His son Charles, after whom Charles Terrace in Dalvait Road, Balloch, was named, was MP for Ayr from 1895 until his early death in 1903. Up until his death, Charles continued to live at Lennoxbank House, and he is almost certainly the first and, so far, last, Valeman to have news of his death carried on the front page of the New York Times newspaper.

The family sold Ballikinrain many years ago, although they kept the name in the title of the Baronetcy. It became a hotel for many years, then in the 1960’s a girl’s school called St Hilda’s (you couldn’t make it up). More recently, it has been handling a greater challenge for society, as a school for boys aged 8-12 with special needs. It was the subject of a deservedly sympathetic documentary program on BBC in February 2007.

Sir Archibald’s direct Orr Ewing descendants still live in west Stirlingshire. Some of them have been Grand Master Mason of the Grand Lodge of Ancient and Accepted Masons of Scotland, Scotland’s most senior Mason. The 6th Baronet, Sir Archibald Donald, departed that post in November 2008, and is the only person to have held it twice.

Other Orr Ewings have lived on in the London area. The London based branch maintained the Orr Ewing involvement in Conservative politics. One of them, who was Sir Archibald’s great-grandson, was the Tory MP for Hendon, and was awarded a second Orr-Ewing Baronetcy, although you have to say that “of Hendon” (which was the title he took) hardly has the same ring as “of Ballikinrain”. Later he became a Life Peer.

<top>

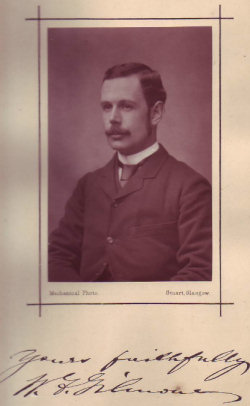

For the Valeman par excellence which he undoubtedly was, William Gilmour had an unlikely birthplace - Torquay in Devon, being born there in 1854. However, if ever there was a case of “that was only because his mother happened to be there at the time”, this was it. William’s parents’ home was at Eaglesham in Renfrewshire, and all of his 8 siblings (he was the 3rd of nine children) were born there or in Glasgow. His father had no business interests in Devon, so quite what his mother was doing in Torquay we don’t know – probably something as simple as holidaying on the English Riviera.

For the Valeman par excellence which he undoubtedly was, William Gilmour had an unlikely birthplace - Torquay in Devon, being born there in 1854. However, if ever there was a case of “that was only because his mother happened to be there at the time”, this was it. William’s parents’ home was at Eaglesham in Renfrewshire, and all of his 8 siblings (he was the 3rd of nine children) were born there or in Glasgow. His father had no business interests in Devon, so quite what his mother was doing in Torquay we don’t know – probably something as simple as holidaying on the English Riviera.

Both his parents came from wealthy Scottish families. His mother was Isabella Buchanan Ewing, sister of John and Sir Archibald Orr Ewing. That is the key connection which brought William to the Vale in the first place - to join his uncle John’s company at Levenfield and Croftengea when he was only 20, in 1874.

Not that he came as a remittance man - a poor relation needing a job to keep the wolf from the door. Quite the opposite in fact, because the Gilmours of Eaglesham were one of the greatest mercantile Scottish success stories of the 19th century, and certainly one of the most interesting. Their story reads like a Victorian morality tale about hard-work being rewarded and comes complete with overseas colonial adventure, frontier living and family squabbles. We won’t concern ourselves with the parts that don’t touch on William Ewing Gilmour, but that still leaves a lot about the Gilmours worth telling.

His father’s family, which by the time of William’s birth styled itself the “Gilmours of Eaglesham”, was even richer than the Orr Ewings. They were one of the great British, never mind Scottish, mercantile families of the 19th century. The founding father of the wealth was William’s great uncle, Allan Gilmour senior, (two other Allan’s feature in this story and the family as a whole was positively replete with them). Allan Gilmour senior decided to branch out from farming, which had been the family’s occupation for a number of generations in the Parish of Mearns, Renfrewshire, into the timber trade. In 1804 he and two brothers, the Pollocks, who had been his schoolmates at Mearns Parish School, set up a company called Pollock, Gilmour & Company to trade in timber. Although the name perhaps suggests otherwise, Allan Gilmour was right until he finally fell out with the Pollocks and left the company 1838, very much the leader and driving force.

The company’s headquarters were in Glasgow, but its operations were based in the new port of Grangemouth, still to-day a major port of entry for timber, to handle the trade with the Baltic, which had been for centuries the UK’s main overseas source of timber. That trade was interrupted by the Napoleonic Wars, when Napoleon banned countries in continental Europe, including the Baltic countries, from trading with Britain.

Pollock, Gilmour & Co was forced to change its focus to British North America (now Canada) and this was the making of the company. About 1806 Pollock Gilmour established a subsidiary, firstly at Miramichi in New Brunswick and later in Quebec and elsewhere in eastern Canada. The company bought huge tracts of virgin forest and felled its own timber with its own foresters, as well as buying from independents. It also expanded its operations to act as general suppliers to the whole lumber industry in eastern Canada. And most importantly, it created its own fleet of ships to carry the timber back to Britain – 50 ships by 1816, while by 1838 when Allan Senior left the company, it had 150 ships, which made it the largest shipping fleet in Britain. The money rolled in from all of these operations.

Allan Snr’s younger brother, James, was William Ewing Gilmour’s grandfather. James joined the company and he was sent to look after its affairs in Canada in 1812. While there he got married to a Scottish girl and started a family. His first son was born at Miramichi in New Brunswick in 1820 and was called Allan after his uncle Allan Snr; this Allan was William Ewing Gilmour’s father. He was therefore a Canadian by birth, and lived in New Brunswick until his teenage years, joining the family firm in Canada as soon as he was old enough.

What brought James and his family home to Scotland for good was a major falling out between Allan Snr and the Pollocks. It had been building up for a number of years because Allan senior felt that they did not show the same commitment to the business which he did, and that he was carrying them. In 1838 he sold out his share of Pollock, Gilmour and left the company. He advised the numerous Gilmour family members who were working in the company to follow suit. Only his brother James took his advice and came home to Renfrewshire with his family, which turned out to be a very smart move indeed as far as his son Allan was concerned.

In Scotland the two brothers, Allan Snr and James, set about using their timber fortunes to acquire land. The Eaglesham Estate was bought from the trustees of the Earl of Eglington in 1844 and within a few years the Gilmours were the 2nd largest landowners in Renfrewshire. Allan Snr was a bachelor and it was expected that he would leave his fortune to his heir-in-law, his eldest nephew, also called Allan Gilmour. In fact, this Allan had stayed with Pollock Gilmour & Co when Allan Snr left, and this alienated the old man, who changed his will in favour of William’s father, Allan. Naturally litigation followed, but the will stood.

So when Allan Snr died in 1849, William’s father inherited a considerable fortune (when his father died in 1857 he inherited the rest of the Eaglesham estate). In 1850, a year after this inheritance, Allan married Isabella Ewing and they had 2 sons before the birth of William in 1854, going on to have 6 other children after William.

Young William was brought up at Eaglesham in the midst of wealth and comfort, based on land-owning, farming and timber. He was sent off to school at Edinburgh Academy, which seemed to have been his parents’ school of choice and after that, he attended Edinburgh University. At University it is said that he was something of an athlete, which is perhaps a pointer to his later enthusiastic support for sports clubs in the Vale. As the third son he was not going to inherit Eaglesham estate, and although independently wealthy, he was looking for something different to do, although land-owning always featured in his business interests.

Soon after graduating from Edinburgh University aged 20 he came to the Vale to join his uncle John’s company in 1874. This was said to be specifically at his uncle’s invitation, which is understandable given that John Orr Ewing and his wife were childless while his brother Archibald and Archibald’s family were well established in their own company just across the Leven. No doubt John had his eye on a family succession in the business and William was being groomed as John’s successor; he just got there a little earlier than was probably anticipated. His rise through John Orr and Co was family-fuelled: William became a partner in 1878, aged 24, just before the death of his uncle John and he was the major inheritor of the Ewing family interest in John Orr Ewing & Co on John’s death in 1878. His involvement with the company and its successor the UTR lasted 50 years, until his death in 1924.

William was a member of a high quality board which oversaw many profitable innovations at John Orr & Co and what perhaps seemed like inevitable growth. However, technical and market changes were afoot and the industry in the Vale had to change with it. When the 3 Vale dyeing companies – Archibald Orr Ewing & Co, John Ewing & Co and William Stirling & Sons – amalgamated in 1897 to form the United Turkey Red Company, William became a director of that company. After the retiral of John Christie from the chairmanship of the UTR in December 1922, William Ewing Gilmour became its chairman and remained so until his death just over a year later in 1824.

While his business career would probably have earned him a footnote in Vale history, that’s not for what he is best remembered here. Rather it is his role in the wider Vale community as benefactor, sportsman, supporter of good causes and local politician. In all of this he was ably assisted by, perhaps in some instances even instructed by, his wife Jessie Campbell. She was the daughter of James Campbell of Tullichewan, a family famed for much of the 19th century in Scotland and further afield, for its support of Liberal and liberal causes. After their marriage in 1882 at Tullichewan Castle, Jessie’s Liberalism and William’s political Conservatism must surely have made for many a lively discussion in the family home.

Initially this was at Croftengea. An interesting side-light on the times was that when the couple arrived back in the Vale from their honeymoon, employees lined the Heather Avenue from the Main Street to the gates of Croftengea to welcome them back in their horse-drawn carriage, presumably to tug their forelocks as the carriage passed. Very regal, or perhaps even feudal. No doubt the welcome was organised by the management, but even by 1882 William had done enough in the community to be a popular figure with the public. They were not at Croftengea for long before they moved, about 1883, to Woodbank House, which was owned by Jessie’s father James Campbell. Woodbank remained their principal residence until they moved full-time to Rosehall in Sutherland (which they had owned for many years) in 1921.

The young William’s feet had barely touched the ground in the Vale when he had his first taste of local government. Aged no more than 21, and resident in the Vale for no more than a few months, he was elected chairman of the Bonhill Parish School Board in 1875. A 21-year old may seem an inappropriate choice to head up a School Board, but the Parish School Board was a creation of the 1873 Education Act with little history and less baggage, so a young fresh mind was probably as good a choice as any, and better than most. Education struck a chord with him and was part of the motivation for the building of the Gilmour Institute, of which more below. He retained the Chairmanship of the School Board for many years, readily supporting schools in various practical ways.

An example of this was that William paid out of his own pocket for all of the children at Vale schools to attend the Glasgow Exhibition of 1888 at Kelvingrove Park. There were 3,000 of them, and a number of trains must have been hired to take them to Glasgow and back. It’s the educational practicality of the trip which still impresses: It would have been the first time that many of the children would have been on a train, or had left the Vale, or visited Glasgow. And the wonders of the Exhibition, which by all accounts were quite stunning, must have made a lasting impression on the children, as well as providing them with a happy day out. He would have been well justified in feeling that it was money well spent – certainly everyone else thought so.

Education was the motivation for his paying for the building of two of the Vale’s most imposing red sandstone buildings – the Ewing Gilmour Institute for men (now Alexandria Library) and the Institute for Women (now the Masonic Temple), both in the aptly-named Gilmour Street. In every respect these fine buildings have stood the test of time and enhance the appearance of the Vale. The first to be built was the Gilmour Institute, as it is better known, whose foundation stone was laid in June 1882, to the accompaniment of a grand parade and Masonic ceremonials, as was the custom at the time. It was formally opened in 1884 and originally housed a reading room and library with over 500 books, as well as a recreation room. It was a great boon to the community and survived in its original form until 1927 when it was taken over by Bonhill Parish Council as its headquarters. It also became the headquarters of the new Vale of Leven District Council when it was created in 1929. Upstairs became a County Council Library, and the building continued in these roles until local government re-organisation in 1974, when all of it was converted to the Library. It has played a leading role in the community for 125 years now.

Having built an Institute for Men, you could well believe that he came under some pressure from his wife to build a similar facility for women, and that’s what he did, further up Gilmour Street at its junction with Smollett Street. The foundation stone for the Institute for Women was laid in 1888 and the building was opened in 1891. Its primary user was the Vale of Leven Branch of the Scotch Girls Friendly Society, but it never established itself in the Vale in the way which the Ewing Gilmour Institute had. By the early 1920’s it was clear that the building was substantially under-used. Ewing Gilmour was withdrawing from the Vale by now, and in early 1921 he sold the building to Lodge Bonhill and Alexandria St. Andrew’s Royal Arch No 321. Although the sale price of £4,000 was a substantial one at the time, the building had cost Ewing Gilmour £22,000 to build 30 years earlier (substantially more than the £12,000 which the Ewing Gilmour Institute had cost). As a well deserved mark of appreciation for these two buildings, what had been Fountain Street was renamed Gilmour Street in the early 1890’s.

The other great interest in which William Ewing Gilmour indulged in the Vale was sport or to be more accurate, sports, because he gave support to many sports clubs in the Vale. His arrival in the Vale more or less coincided with the first flourishing of football in the Vale and it’s hardly surprising that he became involved with many different football clubs which played at various levels at that time. Between them, the Vale of Leven FC founded August 1872, Renton FC (about October 1872) and to a lesser extent Dumbarton FC (December 1872) earned for the Vale the title of “Cradle of Scottish Football”. In that context, William was something of a kindly uncle to football in the Vale (his fellow factory owner and benefactor, Alexander Wylie played a similar role in Renton). Most of the Vale teams with which he was involved such as the Wanderers and the Strollers didn’t last very long. Vale of Leven FC was, of course, another matter.

The ground where the Vale had its glory years, winning the Scottish Cup 3 years in succession, 1877, 1878, 1879, was North Street Park, hard against the railway line at the bottom of North Street. A setting more suited to the Vale’s exalted status was acquired at Millburn, and over the summer of 1888 the club upped sticks (covered enclosure and all) and moved to the newly laid out ground, where it still plays. William Ewing Gilmour and his wife were invited to officially open the new ground in August 1888, but he did even better than that. Before a crowd of several thousand William Gilmour opened the ground from the terrace of the pavilion and then in the words of John Weir in his book “The Boys from Leven’s Winding Shore “ (he) proceeded with the ball under his arm to the field, placed it in the centre of the park and taking a few steps backwards sent it spinning in the air and the game begun”. The opponents that day were Dumbarton and the game ended in a 2-2 draw.

Opening a new sports clubhouse was not new to Gilmour, because he had already opened the Loch Lomond Rowing and Regatta Club’s new clubhouse on the riverbank at the foot of Heather Avenue in 1884, where the Rowing Club stayed until 1975. He had been a supporter of the Club for some time, perhaps because a number of his employees were members, and he also donated a couple of boats to the Club, one named “Lady Gertrude” after wife. That boat was used by a very successful crew which became known as the “Lady Gertrude Crew”. The other Club with which he was associated was the Vale of Leven Bowling Club of which he was the Honorary President for many years.

The School Board was his first foray into local government, but that soon expanded to the County Council. He sat as a Conservative County Councillor for the Alexandria East ward, and served on many of its committees, including the Licencing Board. Keen churchman that he was, he did not share many of Church’s views about alcohol, believing that it had a proper place in society, in moderation of course. Close to his heart was the issue of the Freeing of the Bridges – i.e. removing the tolls from Bonhill and Balloch bridges. While you might expect moneyed interests to stick together this was not the case with the bridge tolls. It was something of an “old landowners” versus the rest issue, because all of the Vale factory owners sided with the Vale population at large against Smollett and Colquhoun and the few local estate owners who took their part. Gilmour and Christie were particularly vocal and supportive of the cause, which can barely have affected them personally. Again, Gilmour appeared as a man of the people.

As well as his career with John Orr & Co William Gilmour maintained a keen interest in agricultural matters. This is hardly surprising given the land-owning and farming background of the Gilmour family, of which William had personal experience as he was growing up. He did not acquire any land or farm locally but that did not stop him from becoming Chairman of the Dumbartonshire and then the Glasgow Agricultural Societies.

His land-owning in the north of Scotland is another matter altogether, and shows a different side to William Gilmour, which lies somewhat at odds with the “man of the people” image which he had acquired in the Vale. Over the years, probably beginning in the late 1880’s, and certainly by the early 1890’s, he began to buy huge land-holdings in the north – it is reckoned that by the time he died he owned about 230,000 acres. These were in the counties of Ross, Sutherland and Shetland – for example he bought the Island of Foula in the Shetland Isles in 1894. He was such a large land-owner in Sutherland in the 1890’s that he was made a Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Sutherland in 1900. By then he already owned the house at Rosehall near Lairg that became his main residence when he vacated Woodbank House in 1921. Even long before that, however he spent a great deal of time there.

In Sutherland almost all of the land which he owned was bought from the Duke of Sutherland. The Dukes, then as now, were notorious for their leading role in the Highland Clearances. In the parishes of Farr and Durness, Gilmour bought some of the most cleared lands in the whole of the Highlands, where some of the worst excesses of the Clearances had been perpetrated on crofting families by Sutherland’s factor, including the burning of cottages to drive crofters out. That he would even deal with Sutherland at that time is perhaps an illustration of the limitations of Gilmour’s image in the Vale, for although these events were about 60 years in the past when Gilmour was buying the land, they were current enough to the remaining crofters. Indeed that part of Northern Scotland featured prominently in the “Crofters War” of the 1880’s, the after-shocks of which rumbled on for another 20 years. Crofters rights and continuing land-owners abuses would have been a current issue to Gilmour in the north.

There’s little doubt about whose side he was on in that dispute. In 1900 he went to the Court of Session in Edinburgh in an action against a crofter on Foula to stop the crofter firstly using some rocks on the sea shore, on which he was drying white fish and secondly to have him remove a shed on his croft which he used as part of his fishing activities. Foula now describes itself as being at “the edge of the world” so its not hard to imagine how remote it was 100 years ago. Nor is it hard to imagine how tough life was for crofters there. So what on earth was William Gilmour doing indulging in typical Highland and Island landlord harassment? Well just conforming to his peer type, probably, because in the Shetlands and much of Sutherland he was, of course, just another absentee landlord.

His wife and he had 6 children in about the same number of years – 5 daughters and 1 son, who was the last to be born in 1889. One of the daughters, Jessamine, died when she was about 11 and to commemorate her Gilmour and his wife built a house at Croftamie in 1898, which they named Jessamine Cottage, to which young girls who worked at the UTR went for a summer holiday. It was well used to begin with, but gradually fell out of favour and was sold as a private house in 1924, after William’s death. It still survives more or less in its original form just to the north of the former Croftamie Primary School.

The other daughters have disappeared from sight. The son, Allan, married an Inverness-shire woman and seems to have spent a lot of time at Rosehall, although his address when he died was given as Woodbank. He died on active service during WW1, in 1917 serving as a Captain in the Lovat Scouts in the Macedonian campaign and is buried near Salonika. He had joined the Lovat Scouts before the war when they were a Yeomanry unit (i.e. mounted Territorials) and since they were headquartered at Beauly, it is a fair assumption that he was then living at Rosehall as his main residence.

However, he and his wife had a son, also called Allan, born at Rosehall, in 1916. That son joined the Army as a full-time soldier before WW2, in which he served with distinction. When he left the army in 1967 he became a County Councillor in Sutherland, chairman of the County Council and later a Highland Council councillor. He served on various Highland quangoes and went one better than his grandfather, becoming Lord Lieutenant of Sutherland 1972 – 91. In 1990 he was knighted for his services to the community. He died as recently as 2003, almost exactly 80 years after his grandfather. The Gilmour family still lives at Rosehall

<top>

As has already been indicated, be prepared to be a bit confused by the naming conventions of the group of Ewing’s who owned and sometimes lived at Strathleven Estate and House from 1835 until 1946/7. Like others, they changed or added to their names if there was financial gain from doing so, and in their case there was a couple of times in the 19th century. At different times Ewing became Maclae and Crum became Crum Ewing. A further idiosyncracy is that they seemed to like the Christian name Humphry, sometimes spelled Humphrey, so there’s rather a lot of them to contend with. However, there is a direct trail to be followed at Strathleven.

Humphry Ewing who was the grandfather of the first of the Ewings to own Strathleven, came from Cardross, so it is possible that the Strathleven Ewings were related to the Ewings of Balloch, if we dig far enough back. Since we don’t, we’ll treat them quite separately.

Its also worth noting in passing that James Ewing’s (who bought Strathleven) eldest brother Humphry Ewing Maclae, married a into the Dennistoun Brown family. This family owned Balloch Castle Estate from 1845 until it was sold to Glasgow Corporation in 1915. So the Ewing connections owned lands at both ends of the Vale for a large part of the 19th century.

<top>

The first Ewing to own Strathleven was James Ewing, who lived from 1775 until 1853. A little further confusion is added by the fact that when James Ewing bought the estate in 1835 for £110,000 (about £6million in to-day’s terms) it was then called Levenside, and had been for nearly 200 years. James Ewing not only changed the name, he also made a number of changes to the House, which had suffered badly from neglect and was in a pretty dilapidated condition by the time he bought it as his country estate from Lord Stonefield.

The first Ewing to own Strathleven was James Ewing, who lived from 1775 until 1853. A little further confusion is added by the fact that when James Ewing bought the estate in 1835 for £110,000 (about £6million in to-day’s terms) it was then called Levenside, and had been for nearly 200 years. James Ewing not only changed the name, he also made a number of changes to the House, which had suffered badly from neglect and was in a pretty dilapidated condition by the time he bought it as his country estate from Lord Stonefield.

The purchase of Strathleven coincided with a number of changes in what had already been a very full business and public life for James Ewing. Firstly, from that time onwards, Ewing withdrew from his high profile public life and secondly, in the following year 1836, he got married. Ewing was in his 61st year and this was his first marriage. His new wife was nearly 40 years his junior, a 23 year old woman who is usually described as beautiful. But this is getting ahead of what is an eventful enough tale as it is.

James Ewing was born in 1775, the 5th child of Walter Ewing Maclae of Cathkin. His father was born Walter Ewing and established himself as a prominent Glasgow businessman based on what to-day we would call an accountancy practice. When he inherited Cathkin House and Estate, a condition of the inheritance was that he added the name “Maclae” to that of Ewing. However his son James never took the Maclae name remaining simply James Ewing throughout his life. Because James Ewing , with his marriage late in life, never had any children of his own, it is the descendants of his sibling who feature in the story of Strathleven, which they inherited on James Ewing’s death. Their family name was Crum, but they in turn added Ewing to become Crum Ewing when they inherited Strathleven. Hopefully, that sorts out the names for now, because life really is too short.

Walter Ewing Maclae’s accountancy practice extended into many fields, but he was particularly involved in what was euphemistically called the “Glasgow West Indies Trade”. This trade consisted of sugar plantations on the Caribbean islands which were worked by slaves. The Glasgow West Indies merchants, therefore, got rich from slavery. They also fought hard to protect it as an institution at all stages of its abolition. Walter was not himself a plantation or slave owner, but many of his clients were.

It was not surprising that when young James finished his formal education at Glasgow University (he went there from Glasgow High School in 1887, aged 12) he briefly worked for his father. However, he soon branched out as an agent on his own account, handling imports of sugar from the Jamaica plantations. He set up the business of James Ewing & Company, in Glasgow, while still in his 20’s, and the business grew so quickly that his father merged his own interests into James Ewing & Co. This company continued to have its headquarters in Glasgow for well over 100 years.

Having started out acting as an agent for West Indies slave plantations, James Ewing quickly realized that there was much more money to be made in actually owning one or two plantations himself. So, he bought a number of estates on Jamaica and one on St Kitts. With them came the slaves, and James Ewing, like many other Glasgow West Indian merchants, was a direct slave owner. Not only that, but the slaves on his plantations were kept in the lowest category of “chattel slaves” which meant that they had no right to life, or indeed any other sort of rights, either.

The slave trade, but not slavery itself, was abolished in the British Empire in 1807, just as Ewing became a slave owner. This was at the end of the first phase of the British campaign against slavery when public awareness of the horrors of slavery was at its height, and public sentiment was overwhelmingly against slavery. Not only that, but Ewing repeatedly received strong contrary advice from within his own family circle. His cousin, Reverend Ralph Wardlaw, was one of the leaders of Scotland’s anti-slavery campaigns, and publicly condemned Ewing’s involvement in slavery. Ewing has no defence in either ignorance or “just a man of his time” - in fact he was moving against the tide of his times. Ewing’s motivation was simply the making of money, and the immorality of slavery never seemed to have entered his considerations then or later.

Although the slave trade was abolished in 1807 in the British Empire, the institution of slavery itself was not abolished by the British Parliament until 1834, after a prolonged rear-guard action by owners such as James Ewing. Even after it had been abolished by the UK Parliament, MPs who had a vested interest in slavery (Ewing was an MP at this time) tacked on a clause which meant that the slaves had to continue to work under the same conditions for another six years. Only direct action by the slaves on Jamaica saw this measure cancelled. Like many leading businessmen in Glasgow and the West of Scotland at that time whose wealth was based on slavery, Ewing’s well-publicised acts of charity and religious piety seem to have been highly selective.

This was not the only example of his selective morality, as we shall see. However, what counted in the contemporary Glasgow social and business circles within which Ewing moved, was not his morality, but his ability to make money and to conform to the Establishment’s policies – “don’t rock the boat” was the watchword of that group. He was always very good at both.

By 1815 he was rich enough to set up a Provident or Savings bank in Glasgow to encourage the working classes to save. In that year also he paid £3,000, an enormous sum for a house in Glasgow in those days, to buy Glasgow House in the hope of encouraging his recently-widowed mother back to Glasgow. This was one of the best known houses in Glasgow at the time and was surrounded by a rookery, which earned him the nickname of “Craw” Ewing. It stood exactly where Queen Street Station now is and James Ewing sold it to the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway in 1838 allow the building of the Station.

Between 1818 and 1819, Ewing’s public life in Glasgow prospered. He became in quick succession Dean of Guild of the Merchants House, which was a very powerful position in those days, President of the Andersonian University and Chairman of Glasgow Chamber of Commerce.

Ewing was therefore the perfect Establishment figure to act as Chancellor (foreman is the modern equivalent) of the Jury at a trial arising out of the so-called “Radical War” of 1820. This was essentially a reaction by weavers in the west of Scotland to their deteriorating financial circumstances in the wake of the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Much of the agitation was being fomented secretly by the reactionary Tory government of Castlereagh and Sidmouth, rather than spontaneous activity by disgruntled weavers, although there was some of that too. The government’s intention was simply to use agents provocateurs to create public protests and disturbances, and to brand the participants as dangerous radicals. A favoured tool of the government agents was to encourage people to swear a secret oath to bring down the government by violent means and thus entrap a few innocent souls, who could be harshly dealt with to dissuade the others from similar action. These agents usually wrote the oaths themselves. Needless to say, there never was any question in the government’s mind of actually addressing the very real grievances that people had.

The role of the government in all this was pretty well public knowledge at the time, although it was vehemently denied by them and their agents, some of whom were publicly exposed. One of the heroes of this exposure was a son of the Rock, Peter McKenzie, who started off in life as a trainee lawyer in Dumbarton and ended as a newspaper owner, Reform leader, and author of such books as “Reminiscences of Old Glasgow” in which he gives a good account of how he used his newspaper to expose the role of one of the worst of the agents, Alexander Richmond. Richmond was then stupid enough to sue him, which only gave even more publicity to the whole sordid episode. McKenzie won the court case, his stance was vindicated and he won pardons for the men who had spent more than 10 years or so as convicts in Australia. Even then the Governor of New South Wales refused to tell the men they were free for another 3 years or so, and they were only released when he was sacked by the new Liberal government in London for his behaviour.

There could be no release for the men who had been executed after State show trials, and James Ewing had a hand in this. One of the participants in civil protest, a Strathaven weaver, James Wilson, who was an old man, was put on trial in Glasgow on the charge of High Treason. At the time it was regarded as an absurd charge by the public at large, but since the 1745 rebellion the Scottish legal system had been a tool of the Westminster government. With Ewing as the foreman, the jury found Wilson guilty of High Treason and not only was he publicly executed, he was then beheaded. Even Ewing’s apologists recognised the barbarity of this whole episode, and try to plead mitigation by saying that the jury recommended mercy. In fact all the jury had to do was to find Wilson Not Guilty, and he would have walked free, as other accused did from other courts. As became clear after the trial, some members of the jury were minded to release Wilson, apart from anything else refusing to believe that this old man represented a threat to anyone. However, they seem to have been persuaded by other jury members that Wilson would be treated leniently and would soon be sent home. That was certainly Ewing’s subsequent line and he always claimed, even to Peter McKenzie whom he knew quite well, that between the verdict and the execution he had worked tirelessly for Wilson’s release, without success. He remained very defensive about his part in Wilson’s death for the rest of his life.

This State Show Trial is eerily reminiscent of the role of another owner of Strathleven (still called Levenside at that time) in the trial and execution of James Stewart, or James of the Glen as he is better known, in 1752 for the murder in Appin of Colin Roy Campbell, the Red Fox. A particular villain in that travesty was Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, Sheriff Depute of Argyll. He had bought Levenside in 1732 and thereafter styled himself “Campbell of Levenside”. Both he and his son John played key roles in the execution of an innocent man at the government’s behest - see William Scobie’s article “The Appin Murder” in Other Contributions on this web site. Now, if any house in the area deserves to be haunted by the ghosts of innocent men, it is Strathleven, but you definitely didn’t hear it here first.

None of this harmed Ewing’s public and business careers, of course. He was a leading promoter in the building of the Royal Exchange in Exchange Place (now the Gallery of Modern Art) in 1827, which was appropriate enough since much of the West Indies trade was conducted there. He was also a prime mover in the creation of a new cemetery for Glasgow, the Necropolis. He actually hosted the meeting at which it was decided to proceed with the grandiose plans for an appropriately grand final resting place for Glasgow’s rich families. Certainly not lacking in ambition or finance, the promoters based their design on what was then and arguably still is now, the most famous cemetery in the world - Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. As a reward, Ewing bagged a top spot in every sense, close to the statue of John Knox at the highest point in the cemetery, presumably closer to God, who you would like to think, had a few unwelcome words in his ear.

Politically, Ewing was regarded at the time as a “liberal” Tory, but that is a very relative term indeed, and he was only liberal compared to the Neanderthals who were then leading the Tory party. His liberalism was strictly limited to matters in which he had a measure of self-interest – a little parliamentary reform and an expansion of free trade.

He was a major beneficiary of the Reform Act of 1832 which saw Glasgow getting 2 MP’s, whereas it had previously shared 1 with 3 other much smaller burghs. Also, the electorate expanded from about 30 in Glasgow (all voting indirectly) to over 7,000 (out of a population of about 250,000 in the 1830’s). Most of this electorate was moneyed and propertied and many only wanted reform to extend to them and to hang with everyone else.

Ewing had been appointed Lord Provost of Glasgow in 1831, so it was no surprise that he was interested in standing for Parliament under the new enfranchisement following the passing of the Reform Act. In 1832 he stood for the first post-Reform Parliament for one of the two new Glasgow seats. Standing as an Independent, Ewing topped the poll ahead of James Oswald, who was also elected. This was undoubtedly a reflection of how well known and respected Ewing was at that time amongst the new 7,000 electorate. This was in fact the peak of his public life and he continued to serve out his time as Lord Provost while a Member of Parliament.

In Parliament for 3 years, 1832 – 1835, Ewing made very little impact. Times were changing and a number of major issues were engaging the public’s attention in Scotland. These included the abolition of slavery in 1834, patronage in the Church of Scotland, which led to the Disruption a few years later in 1843, and the beginnings of agitation for repeal of the Corn Laws, which was actually about cheap food for urban populations and which split the Tory Party for a generation when Peel abolished them in 1846. On these main issues of the day, Ewing either actually was, or, fatally for a politician answerable to a newly-franchised electorate, managed to give the impression that he was, on the wrong side of the argument. His public popularity was on the wane.

In the election of 1835, he again stood for Glasgow as an Independent. This time he was defeated, and his failure to get re-elected signaled his complete withdrawal from public life. His life then entered a new phase.

The following year in 1836 he bought what was then the Levenside Estate for the modern equivalent of about £6 million, and set about the major refurbishment, renaming it Strathleven. The house itself was in an advanced state of disrepair and he did an outstanding job in restoring and renovating it. As it happens, some of the most obvious changes which Ewing made were lost in its restoration in the 1990’s which returned it to its original appearance, but that in no way detracts for what Ewing achieved. He also created a very productive and profitable farming estate, based on rented farms, on the east side of the Vale, from the Murroch Glen to Auchincarroch Road.

All of this created a suitable residence and surroundings to which he could bring his 23-year old bride, Jane Tucker Crawford, daughter of a rich Port Glasgow merchant, after their marriage in 1836. They seem to have lived a happy married life, about which the best known aspect was an extended tour of Europe which they undertook in 1844 – 5. Ewing wrote regular letters to his business associates at home while on the tour, and these form the basis of a book which Rev Dr McKay wrote about him “Memoirs of J Ewing of Strathleven”.

James Ewing died at his town-house in George St in Glasgow in 1853 in his 79th year. There were no children of the marriage, so the estate passed to his nephew, Humphry Ewing Crum Ewing. However, James Ewing’s widow, Jane, had life-time residency at Strathleven. She lived on until June 1896, comfortably outlasting Humphry, who therefore never lived at Strathleven, but rented Ardencaple Castle, Helensburgh.

<top>

Humphry Ewing Crum-Ewing of Strathleven

The names now begin to pile up as different inheritances begin to accrue to members of the Ewing of Strathleven family. We needn’t concern ourselves with the marriages by which these names came to be added, other than to say that Jane, an elder sister of James Ewing, married an Alexander Crum of Thornliebank and succession came through that line. In fact, Humphry Ewing Crum Ewing was something of a last man standing as many others who had precedence in the line of succession to Strathleven fell by the wayside either by dying at a young age or dying without a family, leaving the way clear for him to succeed via his mother, Jane Ewing Maclae. So as James Ewing’s nephew he inherited, adding the “Ewing” as his surname to the existing middle name of Ewing. Both represented money, and in the circles in which he mixed, such things were well understood. For the rest of the 90 years or so in which Strathleven was owned by connections of James Ewing, it was the Crum Ewings who ruled the roost.

The names now begin to pile up as different inheritances begin to accrue to members of the Ewing of Strathleven family. We needn’t concern ourselves with the marriages by which these names came to be added, other than to say that Jane, an elder sister of James Ewing, married an Alexander Crum of Thornliebank and succession came through that line. In fact, Humphry Ewing Crum Ewing was something of a last man standing as many others who had precedence in the line of succession to Strathleven fell by the wayside either by dying at a young age or dying without a family, leaving the way clear for him to succeed via his mother, Jane Ewing Maclae. So as James Ewing’s nephew he inherited, adding the “Ewing” as his surname to the existing middle name of Ewing. Both represented money, and in the circles in which he mixed, such things were well understood. For the rest of the 90 years or so in which Strathleven was owned by connections of James Ewing, it was the Crum Ewings who ruled the roost.

Born in 1802, Humphry Crum Ewing eventually succeeded not only to Strathleven House and estate, but also to the estates in Jamaica and St Kitts. By the time he succeeded, slavery had been abolished for many years so, he was not a slave owner. The plantations, in which he naturally maintained a keen interest, remained the main source of his considerable wealth. For most of his working life he was a director or senior partner of James Ewing & Co, latterly combining his position there with that of Chairman of The West India Association of Glasgow.

In November 1856 Crum Ewing entered Parliament as the Liberal MP for Paisley, having been unsuccessful in the election of April of that year. At this remove, a less likely Liberal MP is hard to imagine, but the Liberal Party of the mid-19th century was a very different beast to what it was to become. It was home to a great many wealthy Victorian businessmen and not a few huge landowners such as the Duke of Devonshire. Crum Ewing served as the MP for Paisley for 17 years, retiring at the 1874 election when he was 72. Like most MP’s, his personal political achievements were hard to find, speaking only occasionally in debates – once to compare the productivity of the “Chinese coolies” then working on his estate with that of slaves still employed in Cuba; what his Paisley constituents made of that speech is anyone’s guess. However, while in Parliament he was a loyal supporter of the Liberal governments which ruled for most of his time there.

In 1873, just before his retirement as an MP, he became Lord Lieutenant of Dumbartonshire, a position he held until his death in 1887. In the year before he died, he broke with Gladstone and the Liberal Party on the question of Home Rule for Ireland. Like many Liberal landowning aristocrats and wealthy businessmen, he joined the Conservative Party, although in Scotland they called themselves Liberal Unionists, believing that keeping the name Liberal in their title gave them a better chance of being elected.

Despite inheriting Strathleven Estate and House, Humphry Crum Ewing never got to have it as his residence. Under the terms of his uncle’s will, James Ewing’s widow, Jane, had a life rent on the estate, meaning that she lived there for the rest of her life. She was 11 years younger that Humphry, so there was always a very good chance that she would outlive him. She did so quite comfortably, living on at Strathleven until her death aged 83 in 1896. For the latter part of his life, Humphry rented Ardencaple Castle in Helensburgh and lived there until his death.

<top>

The first Crum Ewing to actually live at Strathleven was Humphry’s son Alexander, although he had to wait 9 years after inheriting to do so, on his great-aunt’s death. As well as working in James Ewing & Co, Alexander farmed at Keppoch near Cardross. This was disposed of when he inherited Strathleven. During his ownership of the Jamaican estates, they changed from growing sugar to growing bananas, still a major crop in Jamaica. Alexander was typical of the laird of his time in being involved in local government with Dumbarton County Council for many years. He died before World War One and was succeeded by his son, Humphry.

<top>

Humphry Crum Ewing was the last of the Crum Ewings to own Strathleven, which he inherited on his father, Alexander’s, death. In his early years, he also lived at Strathleven, although this changed in later life. His main interest was in the business of James Ewing & Co, and after WW1 he moved its head-quarters from Glasgow to London, but it did retain a presence in Glasgow. His wife and he had already bought a house in the New Forrest, at Lyndhurst in Hampshire, and they spent most of their time between there and the estates in Jamaica.

Their only son, Alexander, was killed in France in the first few months of World War One serving with the Seaforth Highlanders, and aged only 18. They also had a daughter who became Mrs Hamilton.

However, he did not desert Strathleven completely. Every year he spent some time there in the summer months, when he visited all his tenant farmers. The impression is that this was more for a round of visits to friends than any check-up or audit of his properties – he had a factor to do that, after all. Humphry seems to have been popular in the Vale – for instance when Bonhill Parish Pipe Band was formed in 1931, the band members invited him to become its first Honorary President. He was delighted to do so, and remained it Honorary President until his death, which explains some of the classic David McKim photos of the Band taken at the front entrance to Strathleven House both before and after WW2. He was also a Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Dumbartonshire.

In his later years he was living more or less full time in Jamaica. When he made his last annual visit to Strathleven in the summer of 1946, he was too frail to complete his customary round of visits. He returned to Jamaica where he died in November 1946.

His daughter, Mrs Hamilton, inherited the estate. She also lived in the south of England and set about disposing of her Strathleven properties over the next few years, via a property company, Margrave Estates. By about 1950 the Ewing connection with Strathleven was completely broken.

<top>