Stairheid Rammies

Eleanor Thomson recalls West of Scotland tenement life

Paintings, postcards, songs, poems and documentaries all currently extol the dubious delights of Scottish tenement buildings, depicting a way of life romanticised through the rosy tints of stained glass windows on the landings and decorated by the trendy motifs in wally closes.

Paintings, postcards, songs, poems and documentaries all currently extol the dubious delights of Scottish tenement buildings, depicting a way of life romanticised through the rosy tints of stained glass windows on the landings and decorated by the trendy motifs in wally closes.

Nowadays when fewer and fewer people actually remember what tenement living was really all about last century, these looming sandstone buildings with their echoing stairwells are celebrated as works of art.

They have been investigated in detail by academics, sanitised and claimed by painters - here a detail of a Fleur-de-lys from a tiled close, there a shiny brass door knocker or worn steps spiralling upwards, all redolent of the 'splendours' of a bygone age.

The official definition of a tenement is 'a building divided into rented flats, especially in the poor, overcrowded and squalid parts of cities'. How true. In looking at the architectural trimmings found in the up-market examples, we are ignoring the masses who used to live in some of the worst slums in Europe.

Certainly, many surviving tenements, lucky to escape unscathed the blitzkrieg of 'modernisation' that devastated whole districts of our cities in the 1960s, have been tastefully renovated and now make bonnie residences. But in general the Scottish tenements were the scenes of hard living, being overcrowded and often infested with vermin from dirty back courts where the over spilling middens lay.

Some areas, like the Gorbals, became synonymous with and notorious for urban decay of the worst possible kind. However, the tenement in which I lived in 1950s Alexandria in Dunbartonshire was reasonably well kept. We were not allowed to draw on the red sandstone walls with chalk; and street games such as 'stottin' the ba" off walls, especially inside the echoing close mouth, was always met with severe disapproval.

Back greens were regularly mown and kept trim while fresh paint was applied to cellar doors and window frames as the need arose. Windows were brightly curtained and closes were scrubbed every week.

The homes involved high maintenance with draughty doors and window frames (double glazing being unheard of) and warmed by inefficient coal fires that allowed half the heat to vanish up the chimneys. The inconvenient and energy sapping struggle of trying to lug a heavy metal coal scuttle full to the brim from the cellar on the ground floor up to the top landing was an everyday occurrence for some unfortunate neighbours.

Then there was the effort of trying to coax heat from damp newspapers and kindling sticks on a freezing cold Winter's morning, ferny frost patterns decorating the draughty windows and smooth linoleum underfoot.

Coal fires also had to have their chimneys regularly cleaned which cost time, money and sometimes soft furnishings that were ruined by the indelible sooty deposits belched into the room. There was invariably a long-suffering look on my mother's face and great excitement on mine when the sweep and his mate came to clean our chimney, their faces, hands and clothing already black and dirty.

Coal fires also had to have their chimneys regularly cleaned which cost time, money and sometimes soft furnishings that were ruined by the indelible sooty deposits belched into the room. There was invariably a long-suffering look on my mother's face and great excitement on mine when the sweep and his mate came to clean our chimney, their faces, hands and clothing already black and dirty.

Absorbed in the novelty of it all, with childlike innocence I watched the sweep's mate spreading sheets on the floor in front of the fire then draping sacking over the fireplace. Meantime, the sweep himself would have disappeared, his silhouette soon to be spotted scrambling over the grey tiles of the roof with a round flat brush on a rope weighted with a heavy ball. His mate, kneeling in front of the fireplace, would then begin a strange ritual. Down on all fours, he would stick his head into the fireplace then turn until he was facing up the chimney when he would begin hooting like a demented owl.

A distant reply would echo from the sweep high up on the roof. After a few more hoots, they would be satisfied they had the right chimney and a brush would be lowered down from the roof (very hi-tec!). The mate's job was to cover up the fireplace to prevent soot coming into the room. Then there would be a rush of stale air and a soft rumble as the soot came tumbling down. But inevitably there were always sooty deposits on surfaces when he had finished since the precautions were always inefficient. Everything reeked of an acrid smell for days afterwards.

Another method of cleaning the chimney was to shove lit newspapers up the flue to set the soot on fire. This was considered dangerous as it was not unknown for sparks to set the rafters alight or for burning deposits to fall back into the room. We must have been unable to afford the sweep on one occasion because I remember my mother having hysterics while my father tried to clean the chimney in this hazardous fashion. The roaring sound of flames shooting up the flue seemed to last forever and it was only by luck that the roof remained intact. Even so, sparks of hot soot kept flying down onto the hearth, adding to my mother's dismay.

Neighbours often fought on the 'stairheid' over 'weans' who misbehaved. Such 'rammies' were relished by spectators and talked about for months afterwards.

"D'ye remember when Big Ina laid intae Wee Mary?" was guaranteed to generate howls of mirth or solemn head shaking, depending on the cause or outcome of the heated disagreement.

Although this kind of community living encouraged friendly helpfulness, I recall my mother talking about the 'stairheid randies', not over-sexed women but those who rendezvoused on the common landing to gossip.

Running the gauntlet of stony-faced females, arms folded disapprovingly over bosoms, deep in low voiced conversation concerning some perceived scandal in the making (rather like a Les Dawson sketch), was part of normal life.

Our building was labelled 'posh' because the communal toilet was on the middle landing of our close, unlike those down the road where tenants had to walk round to the back court to use the outside loo.

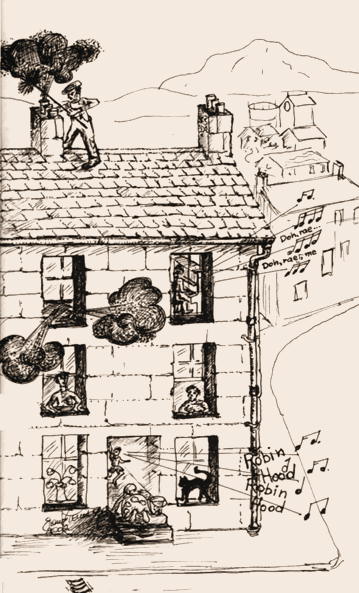

Soundproofing was always a problem in our homes. Our room and kitchen was situated above the close entrance and every noise seemed magnified, whether it was children playing in the street or the downstairs' wee boy discordantly bawling out the signature tune of his favourite TV series -'Robin Hood, Robin Hood, riding through the glen, 'Robin Hood, Robin Hood, with his merry men, 'Feared by the bad, loved by the good, Robin Hood, Robin Hood!'

We managed to squeeze a piano into our flat and I was looked at strangely because I went for music lessons. My plodding arpeggios and hesitant, repeated scales must have driven the neighbours mad and given the 'randies' another subject to digest.

These recollections are fixed in an era now long gone. There were no tiles and no stained glass windows. All the artistry was in living.