Fleet Air Arm Planes Make Emergency Landings in Vale

Apart from the Clydebank and Greenock blitzes of March and April 1941 the greatest threat to the safety of the people of the Vale during WW2 occurred on January 30th 1942, and it came from an unexpected source. On that day four Fairey Aviation Swordfish torpedo bombers from the Fleet Air Arm’s 823 Squadron were flying from RAF Fraserburgh to RAF Machrihanish on a course which took them over Loch Lomond and the Vale of Leven.

The Vale actually lies on the most direct flight path from Fraserburgh to Machrihanish so these planes were exactly where they planned to be and were not lost or off course. The problem was that they started to run out of fuel and were either going to have to find somewhere to make an emergency landing or they were going to fall out of the sky with potentially disastrous consequences for those on the ground as well as the airmen themselves.

The Vale actually lies on the most direct flight path from Fraserburgh to Machrihanish so these planes were exactly where they planned to be and were not lost or off course. The problem was that they started to run out of fuel and were either going to have to find somewhere to make an emergency landing or they were going to fall out of the sky with potentially disastrous consequences for those on the ground as well as the airmen themselves.

As it turned out 3 of the planes came down in the Vale with 7 of the 9 crewmen on these planes surviving while 1 flew on down the Valley and across the Clyde to crash in the Renfrewshire Heights killing all 3 crewmen on board. That there were no civilian casualties speaks volumes for the bravery and skills of the pilots, whose names we do not know, although we do know the names of the airmen who died that day. (See update below.)

You can imagine the agonies which the crews must have been going through – have we enough fuel to make a controlled landing? Where is a suitable site? Can we all use the same landing site? When we land can we stop the plane in time before hitting a tree or wall? Will we survive? Dying in combat was the risk they knew they must take, but the prospect of dying because of a lack of fuel on a training flight must have made them very bitter indeed. But how on earth could something like this happen in the 3rd year of the War when Britain’s air defences had already proved to be a highly competent unit?

This is a puzzle for a number of reasons, even for such a well informed source as the Secret Scotland web-site which does provide some information about 1 of the planes on the flight. Of course, because of war-time reporting restrictions there are no newspaper reports of what happened. No doubt the answers lie in the inevitable Air Accident Investigation Report deep in the Fleet Arm Archives, but so far no one has unearthed it so we have to pick over what is in the public domain to speculate on why these emergency landings happened. We do have one witness to the aftermath at one of the emergency landing sites – Malcolm Lobban, as well as Willie Ronald’s recollections of the rumours in the Vale at the time about the planes. As far as we can tell Malky is the last surviving person who actually saw any of the crashed aircraft – in fact he managed to touch them.

The Fairey Swordfish Torpedo Bomber

Although the Fairey Swordfish aircraft looked old fashioned, being bi-planes with a fixed undercarriage, they were of a relatively modern build with metal replacing fabric in key areas of the air-frame. They carried a 3 man crew – pilot, observer and a radio operator / air gunner all in an open cockpit.

Although the Fairey Swordfish aircraft looked old fashioned, being bi-planes with a fixed undercarriage, they were of a relatively modern build with metal replacing fabric in key areas of the air-frame. They carried a 3 man crew – pilot, observer and a radio operator / air gunner all in an open cockpit.

They first came into service with the Fleet Air Arm in 1936 and during the early years of the war they proved their worth as carrier-borne torpedo bombers in both the Battle of Taranto in November 1940, when they sank or crippled 3 Italian battleships and a cruiser. And of course it was a torpedo dropped from a Swordfish which hit Bismarck’s rudder preventing her from steering towards France and safety.

Two design features of the Swordfish helped the attack on the Bismarck succeed: firstly its speed was much slower than the Bismarck’s state-of-the art anti-aircraft guns were designed to cope with and secondly it came in so low to launch its torpedoes – 18ft above sea or ground level was typical - that the Bismarck couldn’t lower its guns sufficiently to train them on the planes. A low top speed of 138 mph and a very low stall speed meant that it could take off and land in very short distances and it also handled well at very low levels. These were important factors in emergency landings. The aircraft’s inherent robustness helped 7 of the 12 crewmen on that flight to survive, but in any event there is no suggestion of aircraft failure.

The Planes’ Course

As we’ve said the planes were on course and were not lost. The distance from Fraserburgh to Machrihanish is about half of the Swordfish’s operational range of 546 miles, and the Vale is a little more than halfway between the two aerodromes with no navigational obstacles in between which could not be handled by the Swordfish’s 19,000 feet operational ceiling. The planes would have been approaching the Loch and the Vale from the direction of the Trossachs Hills with the Campsies and then the Kilpatrick Hills more or less due south. The pilots would have known to avoid both of these ranges of hills no matter how low their fuel was.

The sight of Loch Lomond and then the Vale of Leven with the probability of flat ground must have come as some relief and it was in the Vale that 3 of the pilots looked for suitable places to make emergency landings. What they would have been looking for would have been a piece of flat ground free from obstructions such as trees, rivers, high walls and buildings.

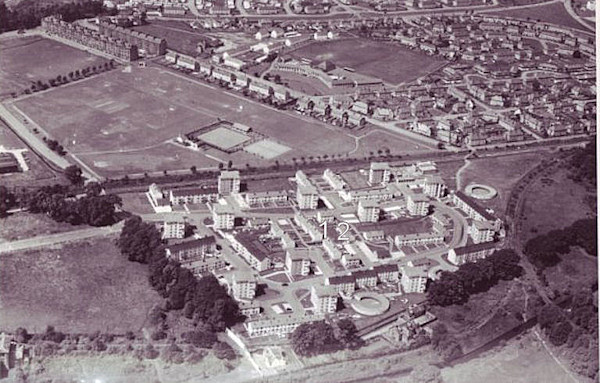

The accompanying photograph taken a few years later by an RAF plane flying on a similar flight path to the Swordfish but probably a little higher and in good weather gives the best impression that we are likely to get of what the Swordfish pilots could see and what choices they had as they approached the Vale of Leven coming in over Loch Lomond. No significant feature had changed since January 1942. The photo more or less centres on the River Leven and there is no view of the Carman hillside although there is a good view of the other side of the Valley from Balloch Park over Jamestown towards the Golf Course and the Targets all the way to Dumbarton. In truth its almost certainly a far better view than the pilots actually had on that January day.

The accompanying photograph taken a few years later by an RAF plane flying on a similar flight path to the Swordfish but probably a little higher and in good weather gives the best impression that we are likely to get of what the Swordfish pilots could see and what choices they had as they approached the Vale of Leven coming in over Loch Lomond. No significant feature had changed since January 1942. The photo more or less centres on the River Leven and there is no view of the Carman hillside although there is a good view of the other side of the Valley from Balloch Park over Jamestown towards the Golf Course and the Targets all the way to Dumbarton. In truth its almost certainly a far better view than the pilots actually had on that January day.

What we don’t know of course is what the fuel levels were on any of the planes and whether the engines were still running on the 3 which landed in the Vale. If the engines had stopped and the planes were in a glide then they were virtually certain to land somewhere along the line of travel they were taking when they lost power.

Where to land?

As you can see, many of the open spaces had trees as inconvenient obstacles, which ruled them out. However, without doubt the east side of the Leven offered the best landing site of them all – on the Carrochan Road between Balloch and Jamestown, identified as "1" on the photo. In those days it was practically a new road, it was as straight as a dye – this is nearly 20 years before the roundabout was built - and in January 1942 there would have been practically no traffic on it. Beyond it is Jamestown Public Park, the Rickett Moss, the fields of Jimmy Kinloch’s farm and the Golf Course, all of which offered good landing sites. These are identified as 2.

Contrast that with what is on offer in the photograph on the west side of the Leven – only two possible sites in the photo: one more or less towards the top middle of the photo, the other more to its immediate right. The first of these, identified as site 3 is the Boll o Meal Park (now Rosshead Housing Estate); the other is the Argyll Park identified as site 4. In this photograph and in reality the Boll of Meal looks a more difficult site on which to land, although it does look as if it has a slightly longer landing area than the Argyll Park.

The whole approach from the north is over the trees of Fisherwood and although the pilots probably wouldn’t be able to make it out until the last minute, the Balloch – Stirling Railway line whose junction with the Balloch – Glasgow line was at the north-west corner of the Boll of Meal. They would surely have been able to see the trees and the wall in Heather Avenue as well as the Craft Stalk. Also, the Boll o Meal sloped from west to east and wasn’t flat in a north-south direction either, but the Swordfish would have been able to cope with that in good conditions.

On the face of it landing in the Argyll Park looks a better bet, even from the north but especially from the west. From the north the approach was more open, offering better visibility of the landing area, and there look to be no trees, walls or factory chimneys at the southern end of it. This approach did have one draw-back which may have influenced the pilots - it would have taken the planes over the houses of Levenvale with the terraces of Argyll Street and Govan Drive just to the right leaving little room for error. With the benefit of local knowledge and hindsight we know that a landing from the west onto the Argyll Park was the best option on the west side of the Leven, but maybe there was not enough fuel for such a manoeuvre.

With the benefit of local knowledge and hindsight we know that a landing from the west onto the Argyll Park was the best option on the west side of the Leven. The Argyll Park had been officially opened on 21st September 1940 – 16 months previously – and the cine clip which we have from the opening shows that it was in mature condition even by then. The Park is clearly shown in the photo of Rosshead (below) in 1966, and with a couple of minor exceptions - the row of trees along the western side of the Park which wouldn’t have been at that height in 1942, and the Bowling Green, - it is virtually identical to what it would have been like in 1942. Landing across the two big football pitches and the small one or the hockey pitch was a very good option. It is certainly Malky’s opinion based on where the planes ended up and the fact that they were both facing the Leven that they landed from this direction, but instead of putting down in the Argyll Park, crossed the railway line to land in the Boll o Meal.

We don’t know the exact weather conditions but we do know that there was snow around which would have made identifying ground contours even more difficult. As we shall see none of the pilots chose the safest and easiest landing site on the Carrochan Road and that suggests that perhaps visibility was poor, although it is also possible that by the time they reached the Vale they were already too low to see all the options which were open to them, especially Carrochan Road.

What the pilots did in the Vale.

We know definitely what 3 of the pilots did and we are able to surmise what happened to the 4th plane from Willie Ronald’s account of the stories which circulated in the Vale. Two of the planes managed to make emergency landings in the Boll o Meal Park although the two planes met slightly different fates. Malky recalls that, “Plane Number 1 (on the Rosshead photo) had its landing gear flattened and although otherwise not too badly damaged it seems to have belly-flapped. Plane Number 2 seemed to be in good condition and on its wheels. Both were quite close together and may have come down that way and they were definitely near the middle of the then small grazing field”.

The other plane, however, ended up facing east very close to the eastern wall of the Heather Avenue – the approximate location is indicate by the number 2 (for the 2nd plane) on the Rosshead photo. This plane had sustained substantial damage, particularly to its fixed under-carriage, which was shorn clean off. This suggests that the pilot brought it to a halt by violently swinging it round to avoid hitting the trees and the northern wall of the Heather Avenue. Malky says there was no sign of any casualties in the planes and that when he and his pals came down from Argyll Street to see the planes, they were completely unguarded. There were no policemen, soldiers or Home Guard to chase them away or at least keep they away from the planes. It was the first time that he got to touch an aeroplane. We’re surmising from the fact that the fuselage was apparently intact that all of the crew survived, although they may have sustained injuries in the landing.

The fact that the landing gear was shorn off but no explosion occurred shows that the planes were not carrying torpedoes, at least by the time they landed. If, as is assumed, this was a training flight then it’s very unlikely that they were carrying torpedoes at any stage.

We have no certain knowledge of what happened to the 3rd plane which landed in the Vale, but Willie is able to tell us that the story in the Vale at the time was that it had crashed on Carman Hill and its crew had been killed. No one can say exactly where it crashed on Carman, but we do know that 2 airmen were killed in the Vale landings, including a pilot. It seems likely that fatalities are more likely to have occurred on a hillside crash than at the Boll o Meal and therefore we have attributed the 2 fatalities to the Carman crash. Even at that, one person survived.

The 4th plane

Secret Scotland tells quite a lot about the 4th plane, Registration Number V554. It decided to fly on rather than try to land in the Vale and crossed the Clyde before crashing in the Renfrewshire Heights, close to Calder Dam, near what is now Muirshiel Country Park. It was a remote area but a farm worker had heard it pass over and someone else reported hearing a crash. Obviously it was reported missing and searches were mounted in the area where it was thought to have come down. However it was many days before the plane was found - some accounts say 12 days others say 3 weeks. The problem was deep snow which covered the area which had hampered the search teams. It was found eventually by a local shepherd; the bodies of the 3 crewmen were still in the fuselage.

Why did this flight get into trouble?

We do know that 823 Squadron had only been re-formed about 2 months before, in November 1941 and its web-site says that in January 1942 it was based at RNAS Crail in Fife which was also known as HMS Jackdaw. Crail was one of the Navy’s busiest airfields throughout WW2; it was used for Torpedo Bomber Training and the Swordfish was a torpedo bomber. We also know that the Swordfish which crashed in Renfrewshire, Registration Number V4554, had been delivered new from store at RNAS Donibristle, also known as HMS Landrail to Crail in November 1941, having originally been delivered to RNAS Eastleigh (now Southampton Airport) on 17th July 1941. So it seems reasonable to assume that these were not clapped out, battle-fatigued aircraft nearing the end of their useful life. What we don’t know is how accurate their fuel gauges were.

Of the 5 airman who died the oldest was aged just 22, the others being either 20 or 21. One additional curiosity is that of the 5, records show them as being based at 3 different airfields – Crail (HMS Jackdaw), Donibristle (HMS Merlin) and Macrihanish (HMS Landrail). It was a newly-formed squadron, composed of young airman drawn from a number of air stations in Scotland, still in training rather than operational and taking part in a training or familiarisation flight.

A final twist is that although the 823 Squadron web-site says that the Squadron was based at Crail at that time, other records say that it was based at Macrihanish. So it may well be that the planes had set out initially that day from Macrihanish on a return training flight to the Fraserburgh aerodrome and that they had taken on what was thought to be enough fuel for the round trip. Perhaps on the return they met very strong headwinds – south westerlies are the predominant wind in Scotland, or icing increased their weight. In any event they all ran out of fuel at about the same time so it seems that they had not refuelled at Fraserburgh – an aerodrome which had become operational only 2 months before but which was kept busy by the Luftwaffe in Norway.

All of these factors suggest that inexperience and misjudgement are the most likely causes for the fuel problem, with weather a possible contributory factor.

The question of why they didn’t all land on Carrochan Road must remain unanswered but it is quite possible that by the time they arrived in the Vale they were flying so low that they just couldn’t see Carrochan Road or that it was hidden from them by poor visibility.

The Airmen Who Died

We do know the names of the airmen who died that day. The names of the aircrew of the plane which crashed in Renfrewshire are supplied by Secret Scotland. They also appear on the web-site which supplied the names of the 2 airmen whom we are assuming died in the Vale - naval-history.net, a web-site on which Don Kindell has researched and compiled a comprehensive list of all of the Royal Navy’s casualties in WW2, on a daily basis for each day of the conflict and presented by day and by ship, shore installation or Fleet Air Arm unit

The site doesn’t actually say that these 2 airmen died in an air crash in the Vale. It does say that they both died in an air crash, that they were both from 823 Squadron and that they were both from one of the Scottish air stations already mentioned. There is no record of any other air crash involving 823 Squadron, nor any other FAA Squadron that day, so it seems a pretty safe assumption that these 2 airmen belonged to the doomed flight and that they crashed in the Vale.

The airman who died were:

The Carman Crash:

Air Mechanic 1st Class Charles William Bear or Beer, based at HMS Landrail (Macrihanish) aged 20 from Harrogate, Yorkshire

Sub Lt Leonard F Brown, RNVR, based at HMS Jackdaw (Crail) from Sussex

The Renfrewshire Crash

Sub Lt John Abbot King, pilot, RNVR based at HMS Merlin (Donibristle) aged 22, from Leeds

Air Fitter Richard Glenyster Williams, based at HMS Landrail (Macrihanish) aged 20 from Glamorgan

Air Fitter Norman Frederick Matthews, based at HMS Landrail (Macrihanish) aged 21 from Hounslow, London

Unfortunately we do not know the names of the 7 surviving airmen, who included the other two pilots who landed their planes without harm to the people of the Vale.

Update February 2016

This above was originally written in 2012 and based on what we knew at that time. Since then further information has come to light. We received this in an email from Jim Newton, the son of one of the surviving airmen.

"Dear Sirs,

Whilst looking into my late father's (Sidney Newton 1919-1992) war time service I came across your article about some Fleet Air Arm planes making an emergency landing in the Vale on 30th January 1942

My father was an air mechanic with 823 squadron at the time of the incident and I believe he was on board one of the Swordfish. I remember him telling me his tale of crashing in a Swordfish. From what I can remember, for it was some 30 years ago, it goes something like this:-

It was his first time flying and he was one of the advance maintenance party flying to Machrihanish to set up for the transfer of the squadron which would arrive later. The aircraft encountered a snowstorm which was too bad for them to continue and so had to find somewhere to land. The pilot offered to let him parachute out but my father said if the pilot was staying with the plane then he was too! Has they came down towards some flat land they crossed a railway line just has a train passed underneath them. They had landed without injury in a park, however my father said that he needed a clean pair of underpants!! The town people took them in and looked after them very well. I do not recall my father mentioning any casualties or the name of the town.

His records show that he was with the 823 squadron at HMS Merlin, Donibristle, from 9th December 1941 until 1st February 1942 when he moved to HMS Landrail, Machrihanish. I had always assumed that the planes were flying from Donibristle although I don't recall my father saying which station they were flying from.

The fact that some of those killed were fitters or mechanics and not normal aircrew would support my fathers tale that they were a maintenance party. It would some 40 years later before he would fly again when my mother persuaded him to fly to the Channel Islands for a holiday.

I know that it is some time since I heard my father's tale and some of the facts may not fit in but I hope that you find the information useful.

Yours sincerely

Jim Newton"

Jim's email makes fascinating reading as well as filling in a number of the key gaps in our knowledge about happened that day.

1. The role of the the weather. It was known that there was snow around, but we didn't know that the planes were flying through snow and that a snowstorm was the key decision in making a forced landing. In fact the 4th plane, the one which did not come down in the Vale of Leven but flew on for another 20 miles or so before crashing in the comparatively low hills of Renfrewshire, was lost in snow drifts for many days.

2. The purpose of the flight. 823 Squadron had only been reformed 2 months previously and was based initially at Crail in Fife. However records of its movements are quite confusing immediately before 30th January 1942, although all agree that it was based at Macrihanish from about February 1942 onwards. Its generally agreed that the 4 planes were flying from RAF Fraserburgh, which had recently opened and it seems that the Squadron had moved there not long before from one of the RNAS fields in Fife, Crail or Donibristle. That it was actually on the move from Fraserburgh to Macrihanish around that time and that the four plane flight which crash landed was part of that move was a new revelation to us.

3. Why there were so many ground crew amongst the killed. Of the 5 men who died on the flight, 3 were ground crew - 1 air mechanic and 2 air fitters. Until now this seemed to confirm that the flight was part of a training or aircraft proving flight, but now we know they were part of the move to Macrihanish. It also explains why the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records show the ground crew as being based at Macrihanish; by the time the CWGC was collecting the information, the Fleet Air Arm records would have shown that the men had already been transferred to Macrihanish.

4. The direction in which the planes landed. Jim's father's description of the ground immediately prior to landing confirms that the planes landed from the west, as Malcolm Lobban who saw and touched the planes soon after they landed, had thought. They came across the football pitches of the Argyll Park and then the Balloch-Glasgow railway line (on which the train was passing) immediately before landing. Both the Argyll Park and the railway line are more or less as they were in 1942, although the Boll o Meal Park is now a housing estate. The railway line was the western boundary of the Park. Assuming it was a passenger train you have to wonder what the train crew and passengers made of the planes coming down over them.

Jim's father's recollection was entirely accurate about where he landed and it sounds as if he was in the plane whose landing gear was intact. His facts certainly fit in with the overall scenario and correct some of the assumptions which we had made. We're very grateful to him and to Jim for providing this additional information.