Brief History of Alexandria 1800 - 2008 - Page 3

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 4 | Page 5

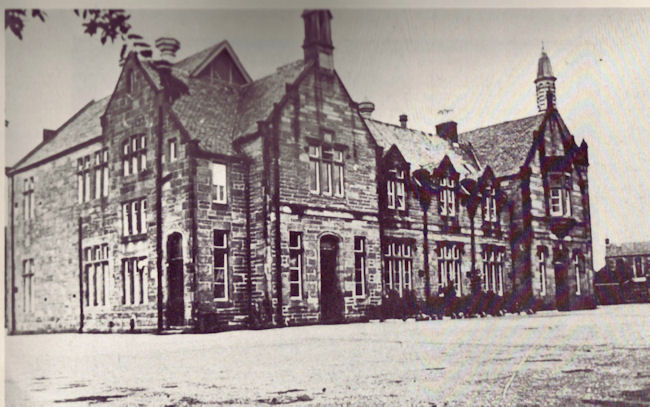

Also about 1850, Main Street school was built by the Parochial School Board (i.e. it was the then equivalent of the state school) where it remained until 1963 when it moved into the old Vale of Leven Academy buildings and was renamed Christie Park School. Its site is now Alexandria Community Centre and its car park. Main Street School started off at about an eighth of the size it eventually became, and was expanded not just as the population grew, but also as other competing subscription schools closed down. Even after the legendary James Mushet became headmaster in 1857, the school roll at Main Street was the smallest of all the schools in Alexandria, but within a twenty years virtually all of the subscription schools had closed.

By 1879 it had been extended to accommodate 613 pupils with an average attendance at that time of 448 day pupils and 78 evening pupils. Mushet remained headmaster of the school until 1896, dying just a few days after retiring. Just as the Parish Church became known as “Kidd’s Church” after the long-serving minister, so Main Street School became “Mushet’s School”.

Nearly all the incomers to Alexandria through the 1830’s and 40’s, continued to come from the Highlands and Argyllshire. But things were beginning to change, with both English and Irish workmen arriving to fill employment gaps. The census of 1851 showed just 12 Roman Catholic families in the whole of the Parish of Bonhill. That seems a low figure. A clearer indication of the changing mix of Vale folk is that in 1859 the first Roman Catholic Church in Alexandria, was opened, Our Lady and Saint Mark’s. It had sittings for 352 people. The 1847-9 potato famine had driven about one million people out of Ireland, and many thousands had come to the west of Scotland. Many had worked on the building of the railways and in the construction industry, and many settled in the Vale. A few years later, in the1870’s, the first Roman Catholic school in the Vale was opened in North Street Alexandria. In 1871 there were 112 pupils enrolled at the day school with a further 154 attending night school. However it was 1876 before a school building was opened opposite the Our Lady & St Marks Church in North St, the first Roman Catholic school in the Vale. By 1880, average attendance at this school was 119 with an additional 90 attending night classes. This school continued in use until the building of St Mary’s school in Bank St, adjacent to Our Lady and St Marks on part of the old Ferryfield Works site, which was formally opened on Friday 21st April 1933 by the Archbishop of Glasgow, Most Reverend Donald Macintosh DD.

In 1861 the Vale of Leven Co-operative Society Ltd was formed with 25 members. It soon opened its first shop, a grocers, at the corner of John Street and Bank Street. The Vale Co-op was based on the Rochdale Principles, based on guidance laid down in a book by the Rochdale Pioneers Equitable Co-operative Society which was founded in 1844. It was not the first Co-op society, but its Principles soon became the basis on which the Co-op movement spread throughout the country, particularly the industrial areas of the country. These principles on which the Co-Op was founded were sound for the time – ownership and management participation by the customers, who were in the main ordinary working people, reduced costs and therefore lower prices, by the economies of scale of bulk purchase and / or manufacture, and a share out of the profits at the end of the year to all of the shareholders.

In 1861 the Vale of Leven Co-operative Society Ltd was formed with 25 members. It soon opened its first shop, a grocers, at the corner of John Street and Bank Street. The Vale Co-op was based on the Rochdale Principles, based on guidance laid down in a book by the Rochdale Pioneers Equitable Co-operative Society which was founded in 1844. It was not the first Co-op society, but its Principles soon became the basis on which the Co-op movement spread throughout the country, particularly the industrial areas of the country. These principles on which the Co-Op was founded were sound for the time – ownership and management participation by the customers, who were in the main ordinary working people, reduced costs and therefore lower prices, by the economies of scale of bulk purchase and / or manufacture, and a share out of the profits at the end of the year to all of the shareholders.

These were very attractive ideas to people at the time, and the Vale Co-op soon prospered. It quickly had a whole range of shops in the villages of the Vale – grocers, bakers, butchers, fish-shops, chemists, clothes and shoe shops, furniture shops as well as vans on the road, some horse-drawn well into the 1950’s, to reach remoter customers. It was also extended its ideas into house-building and owned a number of tenanted properties throughout the Vale. As part of its membership of the national Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society movement, it offered a range of other services such as funeral undertaking, holiday camps, and banking.

A very obvious example of its success was the opening of the Co-operative Halls in Bank Street. The foundation stone was laid in 1895 amidst a ceremony which would not be out of place at a modern PR bash, and the Co-op emphasised its local status by using red-sandstone from Fairview Quarry above Auchencarroch Road (presently the site of Barr’s dump), and as many local tradesmen as possible – e.g. Paton & Ferguson were the masons for the building. It opened in stages, first operations beginning in 1897, while the formal opening was not until January 1904. At street level were shops, while upstairs were the administrative head-quarters of the Society, and the halls which were used for all sorts of social and political functions by the community.

Bank Street and Cooperative Halls

And the social and political contribution of the Co-op should not be overlooked. It had an education committee, a women’s guild, a youth movement (the Woodcraft folk) and a party which contested elections – eventually as an adjunct of the Labour Party. It was little wonder that the Vale Co-op grew quickly – by 1912 it had over 4,000 members, which represented almost 1 member per each household in the Vale, which is certainly saturation coverage at a household level. When it was still in its prime in 1955, just before its decline started, the Vale Co-op’s presence in the community was formidable, as these figures show:

| Number of workers | 225 |

| Number of shops | 42 |

| Number of members | 8,861 |

| Annual Sales | £830,486 |

A fuller picture of all the Vale Co-op's activities over the years is given in a separate entry in the History of the Vale of Leven section of this web site.

The Balloch Cooperative Shop

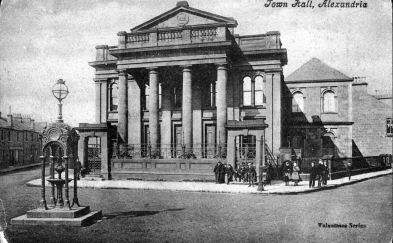

The 1860’s were the beginning of a 40 year a period of strong community spirit in the area which showed itself in many ways. In 1862, the year after the founding of the Vale Co-op, the Public Hall was opened in Bridge Square on the site it still occupies. It was built by a limited company owned by many of the leading Vale businessmen of the day. As soon as it opened it became popular for concerts and shows, religious and political meetings and within a few years its capacity had to be extended.

The 1860’s were the beginning of a 40 year a period of strong community spirit in the area which showed itself in many ways. In 1862, the year after the founding of the Vale Co-op, the Public Hall was opened in Bridge Square on the site it still occupies. It was built by a limited company owned by many of the leading Vale businessmen of the day. As soon as it opened it became popular for concerts and shows, religious and political meetings and within a few years its capacity had to be extended.

Its side rooms became popular for wedding receptions – a function they were still performing in the1960’s. The Vale of Leven Mechanics Institute and Library transferred its activities to the Public Hall from Dalmonach Hall soon after its opening, and remained there until the Institute ceased its activities in 1897 / 98. The Public Hall itself got a licence to show moving pictures in 1911, but still for a long period retained its function as a meeting and entertainment venue, having turns between pictures. Eventually roles were reversed and it became primarily a cinema, renaming itself the Hall Cinema which it remained until 1973. It then became a bingo parlour for a few years. It is now ( Feb 2014) used as a furniture shop.

In 1862 another fine building was opened in Bank Street, as it now was – by the Clydesdale Bank. Ferry Loan had been renamed Bank Street in the 1850’s when a small bank which up until then had operated in Ferryfield House, relocated to Bank Street close to Bank Street’s junction with Mitchell Street. It was run by a man named Guthrie, who was a part owner at various times of Ferryfield Works.

We have already noted how the Old Oak Tree had to be chopped down in 1865. It had served as an unofficial meeting point for over 70 years – a kind of rostrum at whose foot politicians, clergymen and anyone with a point of view they wished to publicly express would gather. And there were plenty of issues to declaim, particularly electoral reform.

It might seem that the Vale was not a particularly radical place in those days – any town whose inhabitants would pay to erect a monument (the Fountain) at one end of a street, to a “kind and just landlord”, who was swindling them by tolls at the other end of the street, could hardly be called bright, never mind radical. Also, this “landlord”, Alexander Smollett, was also the local MP for many years, as a Conservative.

He was such a poor parliamentary performer that when an opponent complained in Parliament that he couldn’t understand what Smollett was saying. At this point Disraeli, a fellow Conservative MP, who went on to become Queen Victoria’s favourite Prime Minister, and who, you might have thought would have been on Smollett’s side, intervened. He said that he couldn’t understand what Smollett was saying either. This, said Disraeli, was because Smollett himself didn’t understand what he was talking about. Smollett never spoke in Parliament again.

Many in the Vale well understood the fundamental problem which was manifested by the election of people like Smollett – the lack of a vote for the vast majority of the people, and the need for electoral reform. Clear proof of this is that even after the 1875 “Ballot” Act, the electorate for the whole Dumbarton county seat (which was Dunbartonshire minus the burgh of Dumbarton, which belonged to the Kilmarnock group of burghs to elect an MP, and no, you’ll never live long enough to want an explanation for that one) was just 2,413 out of a total population of the constituency at that time of 49,693. To judge by the turn-out for reform meetings, the majority of people in the Vale supported the mid-century Chartist movement, which agitated for political reform, and in particular, universal suffrage.

The great Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor came to speak in Alexandria including stints under the Oak Tree, as well as at the Public Park, which in those days lay between Bridge Street and the River Leven. After the Fountain was unveiled in 1870, it continued to serve the same function of meeting point for many years. Increasing traffic, including trams and then buses, made it a less popular site, but meetings were still being organised there in the 1930’s.

The great Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor came to speak in Alexandria including stints under the Oak Tree, as well as at the Public Park, which in those days lay between Bridge Street and the River Leven. After the Fountain was unveiled in 1870, it continued to serve the same function of meeting point for many years. Increasing traffic, including trams and then buses, made it a less popular site, but meetings were still being organised there in the 1930’s.

Many important politicians came to speak in Alexandria in the later 1800’s. These included Campbell-Bannerman who became a Liberal Prime Minister, and was a cousin of James Campbell of Tullichewan Castle, and Asquith who later became Prime Minister before and during the First World War. Both spoke in the Public Hall, although Asquith also spoke in a marquee which was specially erected on Millburn Park. From European and international politics came two of the outstanding figures of the 19th century, both of them exemplars of the European fight for national independence and equality in a free nation.

Guiseppe Gariibaldi started his fight for Italian liberation and unification in the1830’s and was still at it until its achievement in the 1870’s. He was famed as the leader of an army of 1,000 red-shirts (red to hide the blood, rather than as an indication of its political leanings) – it is said that Nottingham Forest chose red for their club shirts in honour of Garibaldi. In between he went to help Brazil, Uruguay and the Argentine in their struggles to expel their colonial rulers and finally returned to Italy to help complete the final re-unification.

His international reputation was such that during the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln offered him the command of the Union Armies, but Garibaldi made acceptance of that offer conditional on Lincoln first freeing the slaves, an action Lincoln wouldn’t take at that time. Garibaldi was lionised, throughout Europe and the Americas by all except the most reactionary: the current 20th century equivalent is Nelson Mandela. He made 3 visits to Great Britain but it is the third in April 1864 which is best remembered. There had been numerous Garibaldi committees throughout Britain for a number of years which raised funds for his campaigns those of other liberation movements. As soon as it was known that he was coming to Britain, these committees took on the role of Garibaldi reception committees.

His international reputation was such that during the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln offered him the command of the Union Armies, but Garibaldi made acceptance of that offer conditional on Lincoln first freeing the slaves, an action Lincoln wouldn’t take at that time. Garibaldi was lionised, throughout Europe and the Americas by all except the most reactionary: the current 20th century equivalent is Nelson Mandela. He made 3 visits to Great Britain but it is the third in April 1864 which is best remembered. There had been numerous Garibaldi committees throughout Britain for a number of years which raised funds for his campaigns those of other liberation movements. As soon as it was known that he was coming to Britain, these committees took on the role of Garibaldi reception committees.

On Garibaldi’s arrival in Southampton on 3rd April 1864 he was waited on by deputations from many cities and towns which were very keen to have General Garibaldi come and visit them. Glasgow was one such city and it had an ace up its sleeve in the shape of John MacAdam, a former Chartist leader and now a Glasgow businessman who was recognised as one of the country’s leading Radicals. McAdam was a personal friend and a long-time supporter of Garibaldi and had earned Garibaldi’s high regard by making a horrendous trip in mid-winter to carry funds from Scotland to Garibaldi at his home on the island of Caprera, north-west of Sardinia. The Glasgow Garibaldi Committee was headed by the Lord Provost but it represented the full spectrum of the population from working class clubs and trade unions through the middle and mercantile classes to the aristocracy.

MacAdam served on the Lord Provost’s Committee and as part of the efforts to bring the General to Scotland he wrote to Garibaldi. Garibaldi firstly accepted the Lord Provosts invitation to come north and then wrote in his own hand to McAdam authorising him to organise the itinerary of the trip. On 11th April McAdam announced at a meeting in Glasgow of the Working Men’s Committee for Garibaldi’s visit that Garibaldi had agreed to visit Scotland for 6 days. McAdam’s working plan was that Garibaldi would arrive in Glasgow on a Monday and between Monday and Wednesday he would tour Glasgow, Paisley and Greenock, the Vale of Leven and hopefully the Land of Burns. The Scottish newspapers were delighted to publicise this including the Dumbarton Herald on Thursday 14th April 1864.

Naturally enough this news caused great excitement and a local organizing committee was formed to handle Garibaldi’s visit to the Vale. The Vale organizing committee members were mainly local factory owners such as Archibald Orr-Ewing with not a Radical or working man in sight. It’s a fair assumption that when John McAdam included the Vale on the itinerary he had in mind its strong support for the Chartist movement rather than as an opportunity for the factory owners to show off their brand new factory buildings.

McAdam said that Garibaldi might come to Scotland as soon as Monday 18th April, which would have meant that the most likely date of his visit to the Vale was Wednesday 20th April. However at no time were any dates confirmed, and before an itinerary could be firmed up, Garibaldi would first have to escape the clutches of his hosts in London.

Garibaldi had arrived in London on Monday 11th April to a hero’s welcome the likes of which had never been seen in Britain before. Today we are surprised by the fact that his hosts in London were the Duke and Duchesses of Sutherland, now deservedly reviled for their role in the Highland Clearances. However, at the time they were just another couple of aristocrats who supported a Liberal government laden with Lords and Earls.

At least 600,000 people turned out to greet him in the capital on his arrival at Nine Elms which was actually a large goods station which it was believed, wrongly as it turned out, was big enough to handle the expected crowds. The crowds continued for the rest of the visit, but they undoubtedly caused concern in some influential circles. In particular, Queen Victoria was very unhappy at Garibaldi’s reception by the masses, seeing in it the threat of revolution and socialism (although one senior policeman who guarded her on many of her trips said that she was jealous because the crowds for her were nothing like as large as they were for Garibaldi. It’s also the case that the Prince of Wales paid a private visit to Garibaldi and the pair got on very well together.) Nor were foreign governments such as France and Austria, who were enemies of Garibaldi, best pleased. It’s also fair to say that Garibaldi was still carrying a wound in his foot from the fighting in Italy and the round of meetings, receptions, breakfasts, lunches, teas and dinners was truly ferocious which would have tested the stamina and constitution of any man.

You can still take your pick about whether the government quietly asked Garibaldi to leave or whether he came to the conclusion that it had all become too much for him to cram into one visit and that he could cut his visit short and return sometime soon to take up the outstanding invitations. Whatever the real cause of his curtailment of the trip was, his impending departure was leaked to the newspapers on 18th April, quoting ill health. Few people believed that story, especially when Gladstone was forced to admit in the Commons that he had paid a night-time visit to Garibaldi to express the government’s concern about his health on the evening of Sunday 17th April and to recommend that he cut short his visit. In any event Garibaldi left London for Cornwall and he set sail from Saint Mawes near Falmouth for Italy on the Duke of Sutherland’s yacht on 28th April 1864.

So he never did visit Scotland nor the Vale – in fact the furthest north he got was Bedford – and there never was to be a follow up visit by Garibaldi to the British Isles.

However, you wouldn’t know that the trip to the Vale never took place if you read John Neill’s “Records and Reminiscences of Bonhill Parish” published in 1912. He has an account of Garibaldi coming to Alexandria which could have been advance public relations copy from John McAdam himself. According to Neill, when the General arrived by train at Alexandria he was met by a large and enthusiastic crowd, and his carriage was drawn by apprentices from the local works to the Vale’ FC’s North Street ground to address a meeting, again through crowded streets. Reports from the time estimate the crowds at between 20,000 and 30,000, and given that Alexandria’s population was about 9,000 at the time, the majority must have come some distance to see Garibaldi. All of this was sheer invention, of course, and we’ll probably never know what source the usually reliable Neill had for that story.

These visits to Alexandria, imagined and probable, are indicative of the profile which the Vale had achieved both politically and economically by the middle of the 19th century at a national level. The editor of the Dumbarton Herald thought that Garibaldi would be coming to see Loch Lomond, MacAdam, old Chartist leader that he was, knew that he was coming to see the workers, while the local organising committee made up of the Orr-Ewings and other works owners were going make sure that he and his press entourage were coming to see the newly-built massive factories of the Vale.

Neill is probably on surer ground when writing of Lajos Kossuth coming to visit William Campbell at Tullichewan Castle. Kossuth was a great Hungarian patriot and leader of the 1848 Revolutions against autocratic monarchies across Europe. After the failure of the 1848 revolutions he was exiled by the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. However he retained huge popularity in Great Britain, second only to Garibaldi and made a tour of Britain in 1856 during which he came to Glasgow and could well have stayed with William Campbell at Tullichewan. Kossuth’s statue is in pride of place in the main square of Budapest, known as Kossuth Square, which also houses the Hungarian Parliament. So if you take a week-end trip to Budapest go along and tell the statue you’re from the Vale and see what that does for Hungarian hospitality.

These visits to Alexandria in the 1870’s are indicative of the profile which the Vale had achieved by then at a national level.

Alexandria continued to grow. Villas were built at the top of Bridge Street in 1868, and in 1878 the old houses at Fountain Place on the south side of the Fountain were pulled down and replaced by the buildings which still stand there. By 1880 Middleton Street was under construction, and two new streets were built to link it to Main street in the centre of the town. One was Hill Street and the other was Fountain Street, which changed its name to Gilmour Street in 1891 after the two Gilmour Insitutes were opened. About 1880, Victoria and Albert Streets were started, and a number of red sandstone tenements built on south Main Street. By 1882 a number of the cottages were added in Middleton Street and Victoria Street was extended. Throughout this time there had been building to the north of the fountain as well, where a number of older building on Main Street had been replaced by the red sandstone buildings of to-day, and Wilson Street was being build upon from the 1860’s onwards.

Sport was beginning to change too. Up until this time the main sports in the area had been rowing, based on Loch Lomond, and shinty. Shinty was played in the Public Park in Alexandria and was brought to the area earlier in the 19th century by the many Highlanders who had come to live here – the first recorded match in Alexandria was 1852.

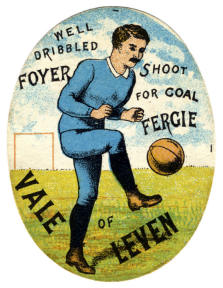

Elsewhere in the west of Scotland football had began to appear, and partly to provide opponents for themselves, but also partly from an altruistic love of the game, Scotland’s premier club, Queens Park of Glasgow, had started to actively promote the game. When they heard that some of the Vale shinty players wanted to learn to play rugby, they immediately got in touch with them and volunteered to come down to teach them the rudiments of football. The Vale boys took them up on the offer, and an exhibition match was played by Queens Park in Alexandria, probably on the shinty pitch in the Public Park, in the summer of 1872.

A host of interested young guys came from all over west Dunbartonshire to see that game, not just from Alexandria, However, the first club to be formed as a result of it was here. On 20th August 1872 a great tradition was born, when a new football club was formed, the Vale of Leven Rugby and Athletic Club. Yes, would you believe it? Rugby. Queen’s Park obviously hadn’t been quite as clear in their explanation of the rules as they might have been.

The Vale quickly changed the name and played their first game, against Queens Park, at Southside Park, Glasgow, on 21st December 1872. Queens Park won 3-0, but the show was on the road. A few weeks later on 11th January 1873, Queens Park came back down to Alexandria to formally open the Vale’s new ground – Cameron’s Park. Although this was a 0-0 draw, Queens Park wisely spent much of the game giving the Vale a refresher course in football – no more of this rugby business, thanks.

From the outset, the game had caught on. A match at Cameron’s Park a few months later attracted 1,500 spectators. It had also attracted some outstanding athletes. For example two of the Vale team were professional runners - James White and John Ferguson – and they were amongst the fastest runners of the day in Scotland. Ferguson, who was the club captain when it won the Scottish Cup in three successive years - 1877, 1878, 1879 – won a one mile race at Powderhall in 1872 in a time of 4 minutes 16.5 seconds. That time would probably still get him noticed today.

From the outset, the game had caught on. A match at Cameron’s Park a few months later attracted 1,500 spectators. It had also attracted some outstanding athletes. For example two of the Vale team were professional runners - James White and John Ferguson – and they were amongst the fastest runners of the day in Scotland. Ferguson, who was the club captain when it won the Scottish Cup in three successive years - 1877, 1878, 1879 – won a one mile race at Powderhall in 1872 in a time of 4 minutes 16.5 seconds. That time would probably still get him noticed today.

By the time they won the cup for the first time, the Vale had moved from their first home in Cameron’s Park, to their second, North Street Park. This move took place sometime before 1876, and it was at North Street Park that the great Old Vale Team of all the triumphs played. The Club moved to its present ground at Millburn in 1888. The 28th April 1888 saw the last game on the famous old Vale ground with Vale beating Renton 5-0. The new season opened with the Vale’s first game at Millburn on 18th August 1888 a 2-2 draw with Dumbarton.

It should be noted that a number of football clubs were formed in the immediate area by players who had attended that inaugural visit by Queens Park in August 1872 – Renton and Dumbarton to name but two – and gave the area a strong claim to be the Cradle of Scottish football, with Queens Park the mid-wife. The Vale folk being the Vale folk, Queens Park must have sometimes wished in the next few years that they had walloped the baby’s backside much, much harder at birth. Anyone who has ever sat on a club committee, of any description, in the Vale, will immediately recognise the behaviour patterns embarked on by the young club. However, that’s a story to be found in the Sport in the Vale of Leven page of the web-site.

By this time a number of other sports were flourishing in Alexandria. The Cricket Club had been founded about 1850, and indeed was only one of three which were founded about the same time, but as we have cause to remark upon again, it proved to be the most durable. It was, therefore, in existence well before the football club was formed. The game was introduced by English tradesmen from Lancashire and Yorkshire who brought their expertise to the textile factories and then to the cricket pitch.

Their first park was adjacent to the Public Park in the triangle formed by Bridge Street, Leven Street and the river. They were there for about 20 years, and in the late 1870’s rented a private pitch in field in what is now Wilson Street. (When they left the Old Cricket Park as it is usually referred to, Angus the Baker built a new bakery on it, fronting on to Leven Street). When Wilson Street was lost to houses, they played at Moss Park and then the Vale Football Park. At last they in 1909 they acquired a lease on the Argyll Park and there prepared an excellent wicket and pitch. It must have seemed to them that their travels were over. However, nae luck; along came the First World War and the Argyll Park was taken over for munitions production. The pitch was dug up for explosives production in a number of dispersed buildings, sunken to contain blasts in event of an accident.

The travels started all over again to Balloch Park, the Argyll Park, the Bowl of Meal, the Argyll Park again, and their present home at Lesser Millburn / Place of Bonhill, beside the river. The club has survived challenges which would have sunk lesser organisations – and indeed a number of larger ones – and its membership has been mainly local for many years.

A Bowling Club was founded in Alexandria in 1867 (a year after the Renton Bowling Club was formed, as its members are always happy to remind anyone from Alexandria), on its present site. Various additions and upgrades have been made to the greens and the Clubhouse over the years, but it has been a fixture - there before most of its present neighbours such as the school and the Park. Both the Vale of Leven and Renton Bowling Clubs are still around in 2013 andlooking forward to their 150th anniversaries in 2016 and 2017.

A Bowling Club was founded in Alexandria in 1867 (a year after the Renton Bowling Club was formed, as its members are always happy to remind anyone from Alexandria), on its present site. Various additions and upgrades have been made to the greens and the Clubhouse over the years, but it has been a fixture - there before most of its present neighbours such as the school and the Park. Both the Vale of Leven and Renton Bowling Clubs are still around in 2013 andlooking forward to their 150th anniversaries in 2016 and 2017.

By 1880 the churchyards were getting full, with very few, if any, new lairs available. A new cemetery was laid out 1880, and the first burials took place in 1881. One of the earliest gravestones, against the northern boundary hedge, carries the inscription “Still here” – where else would she be? That’s an excellent description for this exceptionally well kept cemetery in a truly beautiful setting. Whoever chose the site in 1880 did a great job for future generations of Vale folk.

The North Public School was opened in 1884 as a primary school. This is the present Christie Park School but it has gone through a number of changes to get to that. The opening of this school, which was on the grand scale from day one, with places for 564 pupils, is proof of the growth of the population in Alexandria and increasing demand for primary education. Another major expansion of the building took place in 1894, which was also the year that the first pupils completed 2 years of secondary education. It was raised to the status of a secondary school in 1909, and renamed Vale of Leven Academy.

At that time, another extension gave the school the format and the appearance which it has today. The Academy relocated to its current site at Place of Bonhill in 1962, and Main Street school moved into the Academy building shortly thereafter, when it was renamed Christie Park School after the adjacent Park. That’s a bit ironic, because after the North Public school was opened, what became the Christie Park (and was sometimes known as Notman’s Park), was usually referred to as the School Park.

The Vale Academy continued as a mixed primary and secondary school after 1909 until the opening of Levenvale Primary School in the mid 193o’s when it became solely secondary. It did change appearances a few times when temporary huts were built in the playground. The huts to the left of the main building mainly housed the technical departments, while a newer hut from the 1950’s housed the dining room. They all disappeared when it became the Christie Park Primary School. The old detached red sandstone domestic science and technical department building on Hill Street lasted a few years longer but has now been demolished for many years.

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 4 | Page 5